How I Confronted My Worst Childhood Memory

Twenty-five years after a chance encounter in a middle school bathroom humiliated him, revisiting the episode—and his tormentor—changed the course of the author’s life.

I was ten years old when I experienced a childhood trauma that would last for years. It was 1993. And I’d recently entered middle school in southern Maine. One afternoon I left Spanish class to pee. I entered one of the stalls in the men’s bathroom, dropped my shorts to my ankles, and relieved myself.

What happened next is hazy. What I can recall is that I became preoccupied with something on or around my genitals—so preoccupied that, without noticing, I backed away from the toilet and out of the stall. I stood by the sink examining my balls.

My shorts were still around my shoes when I heard the metal door slam. Standing in front of me was the toughest eighth-grade boy in school. Brandon [name has been changed] was a football star, handsome, and popular. And now

he was incredulous.

“What the fuck are you doing?!”

I froze.

“Are you some kind of faggot?”

Flight kicked in. I gathered up my shorts and ran. Back in Spanish class, I slid down in my seat and closed my eyes. No. I wished the entire experience away.

After that dayin the bathroom with Brandon, I disappeared. I stayed away from the lunchroom, cut out as soon as classes finished. My grades dived. I came to know that particular prepubescent agony of wondering where I fit in. I was sure I liked girls, but the homophobia that existed among boys in blue-collar Maine was so vicious that news of my pantlessness would mean danger, and I had convinced myself it was only

a matter of time before Brandon told the entire school I was gay.

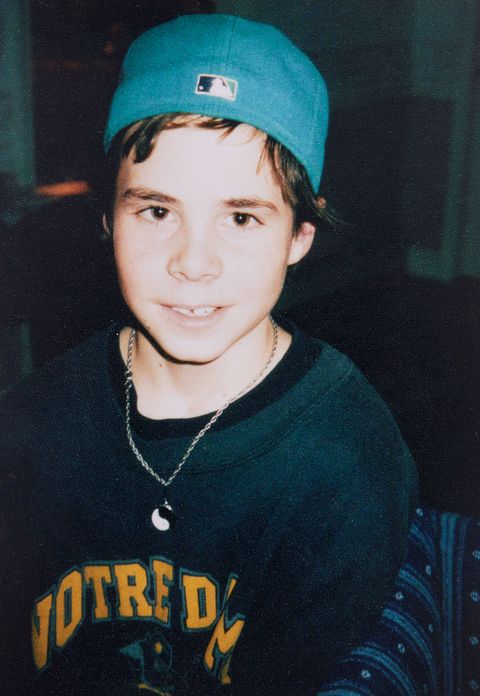

By age 11, I began wearing T-shirts to the swimming pool, covering my body. For years, I hid my face beneath a low baseball cap. Puberty finally hit, bringing brutal bouts of acne with it. Years later, still struggling with my identity, I escaped into drugs. When I finally got sober in 2017, I was confronted for the first time with the vast, shadowy realm of all the parts of me I’d suppressed. Was that sole incident with Brandon to blame for all my years of childhood pain? No. But it was the day I learned that I would have to hide.

I tried every trick that could help me dig through my basement of hidden memories. I had my head shrunk by Freudian psychoanalysts in New York, I had my soul retrieved by a Topanga Canyon shaman, and along the way I learned something transformative: Every time I worked up the courage to reveal a shameful memory, it lost its power—often instantly.

Adults understand that crappy childhood experiences are as common as chicken pox. But kids don’t. By uncovering all the parts of ourselves we’ve hidden, we soothe the awkward sixth-grader in us who was sure his brand of torture was unique.

One afternoon during a breathing exercise with my therapist in Beverly Hills, I remembered Brandon. I couldn’t believe how long I’d repressed the memory, or how strongly the feelings came back. I felt my whole body go rigid. Hesitantly, I revealed to my doc what had happened that day in the bathroom, and the way the shame had haunted me in the years following.

I went home and Googled Brandon’s name, and a Facebook page came up. Had to be him. I kept searching and found his email address. I typed an email: I was a classmate of his from middle school. I had a memory I wanted to corroborate with him, and would he be willing to talk?

Two hours later, a text arrived: It’s Brandon reaching out to you.

I felt a familiar clenching in my chest.

I pulled off the highway and sucked in deep breaths. I thought I might hyperventilate. In all my fantasies of how this might go down, I’d never gotten to the part where I would actually have to

speak to him.

I spent two hours crafting the perfect text message. That evening, I finally mustered the courage to hit send. Less than five seconds after the text landed, Brandon called. Startled, I picked up.

“Yo.”

It was the same deep voice that’d been replaying in my brain for months.

“Hey, Brandon,” I said. “Thanks for—“

“What’s up?” he asked. Cool, aloof. “Refresh my memory.”

When I finished telling my story, he paused for what felt like an hour.

“I came from home economics,” he said, in what sounded like disbelief. “I came into the bathroom and, yeah, there you were, with your pants down. I was scared. I thought, Jesus, this kid is flashing me!I didn’t know what to do!”

I laughed. He laughed.

“I told the kid who sat next to me in home ec about it,” he said. “But I never spoke or thought about it again.”

Then he asked, “Was I mean?”

When I explained to him what he’d said, his voice dropped. “Man,” he said. “That was wrong.”

Then he asked, “Why were you in therapy?”

I told him about my struggle with addiction.

“No kidding,” he said. “I’ve been

there too.”

With the tension defused, and a bond cemented, we laughed like coconspirators, like brothers. We laughed and laughed.

“Look me up next time you’re in Maine,” he said when we finished. “I’m so glad you called.” I thanked him and hung up the phone, triumphant. It was a feeling better than any buzz, any high.

What happens the day after you face something that’s been haunting you for a quarter century? You wake up at 4:00 a.m., electrified. The most shameful moment of my life resolved. The most epic fear reduced to laughter. Had it really happened? In the weeks and months that followed that phone call, my life was transformed. I smiled more. I obsessed less. Hours I’d spent scrutinizing my skin and body in the mirror were alchemized into time I spent out in the world, lighter, freer. Relationships with the older men in my life—even the tough, macho types I realized I’d always projected Brandon onto—became easier. I experienced the world less as a scared boy and more as an upright man.

In recovery I’ve learned the places within ourselves we dread going are

the places we must go. And sometimes we find something we could never expect. A story, a narrative I’d held on to for years turned out to be just another experience shared by someone who saw it from a different angle. His explanation of that set me free. As Brandon said, “I can’t believe that day haunted you for all this time, and I never thought about it again.”

7,032 Responses to How I Confronted My Worst Childhood Memory