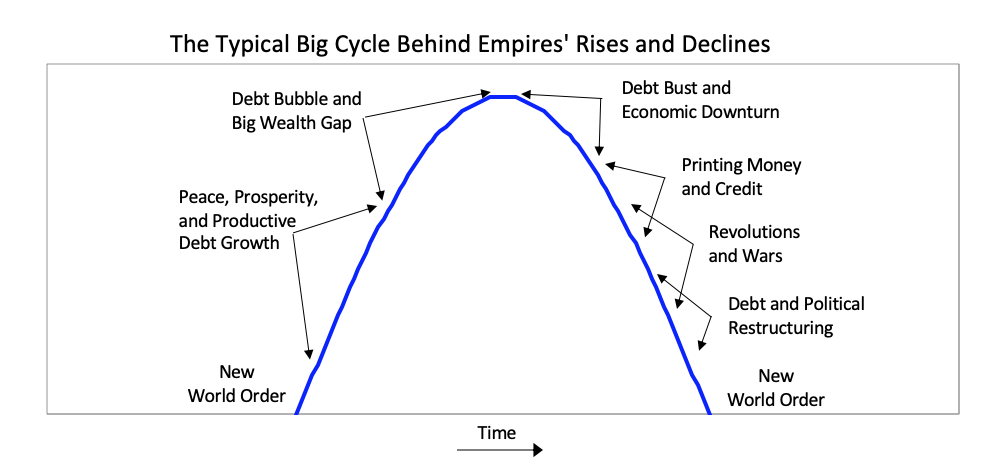

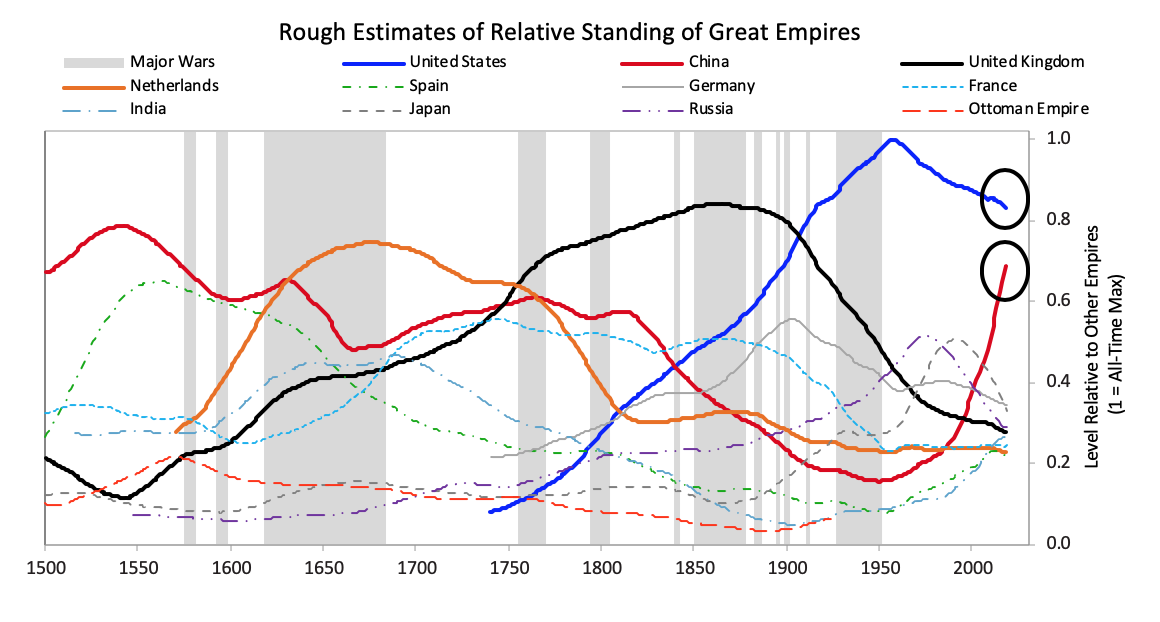

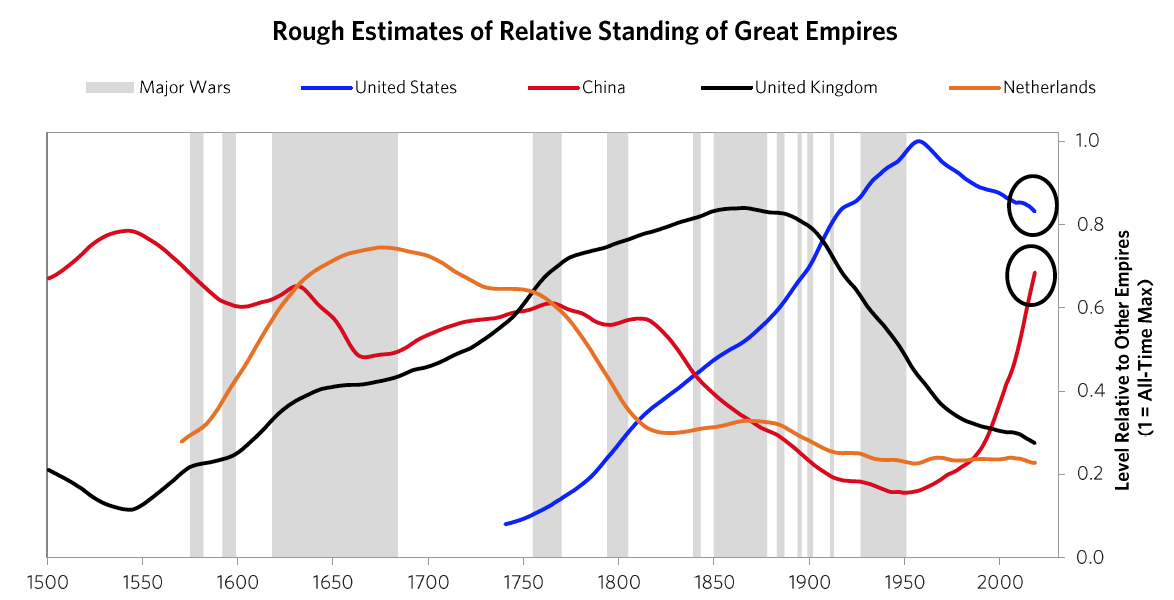

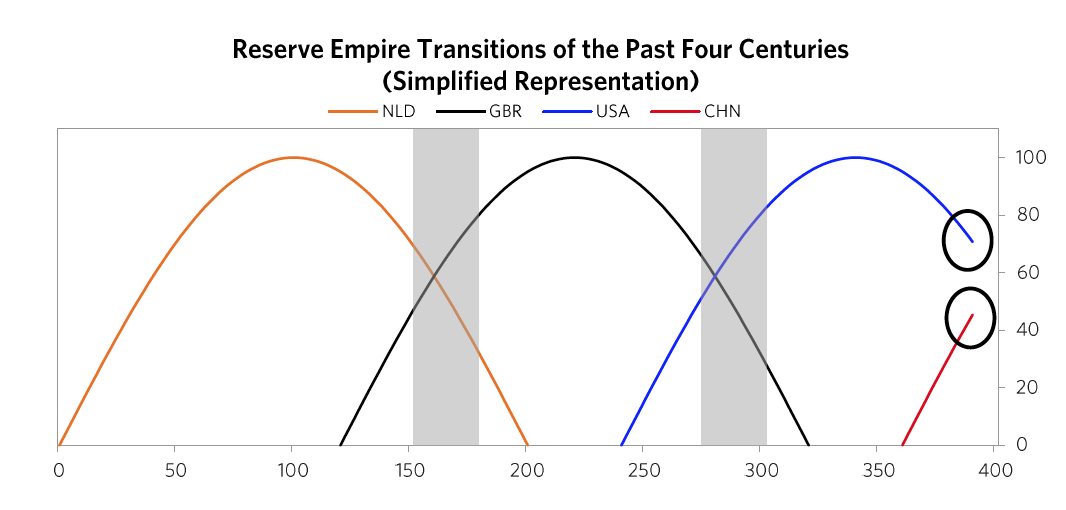

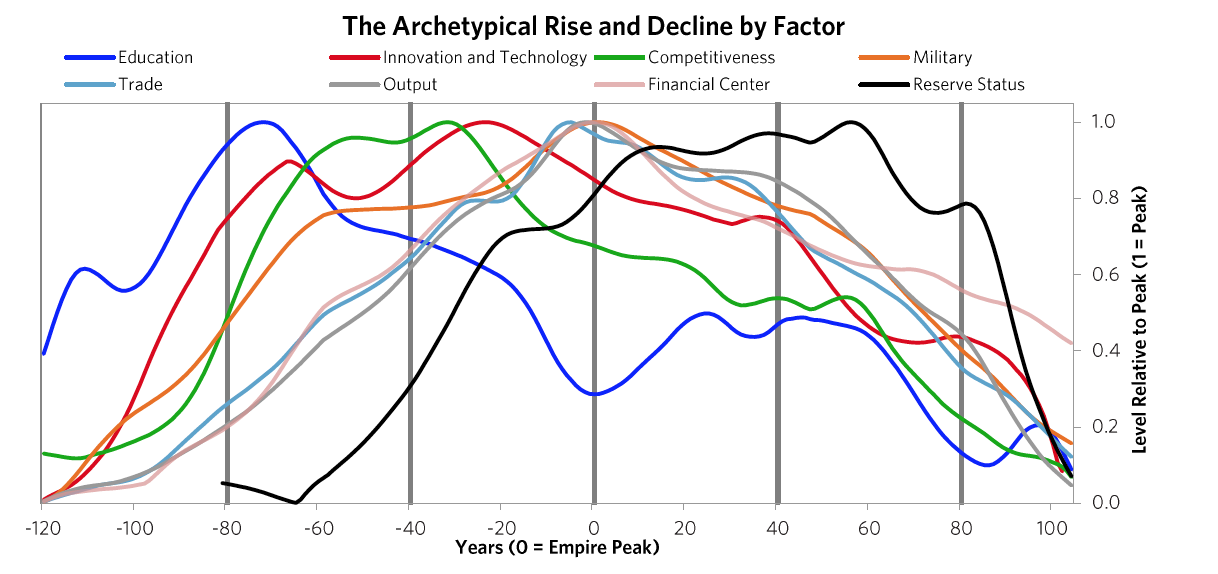

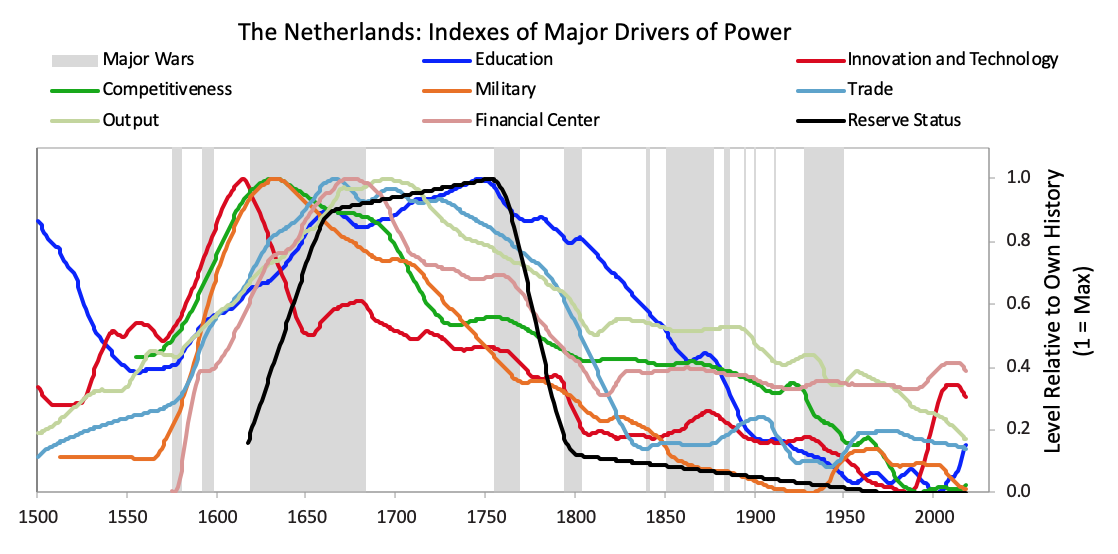

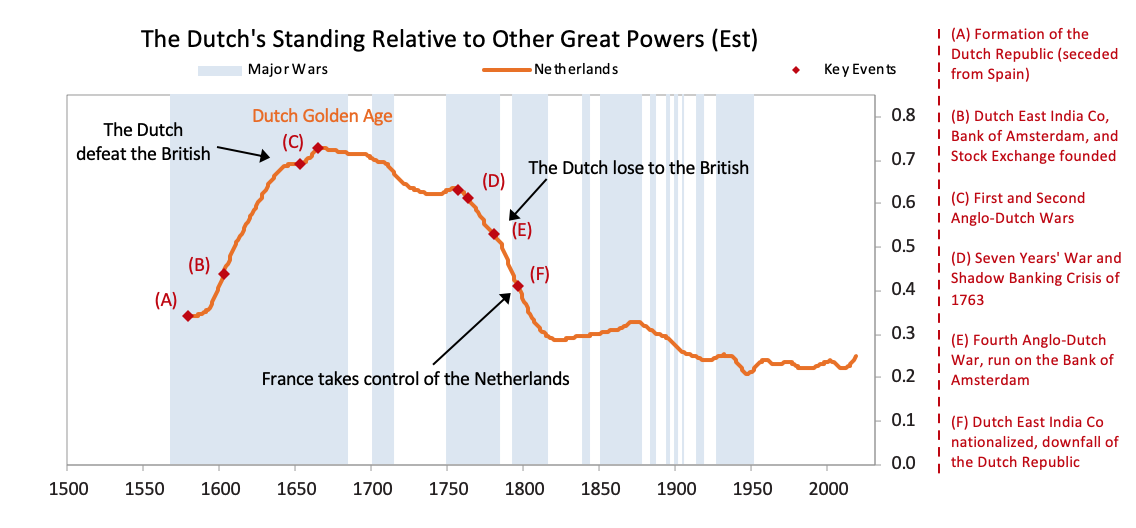

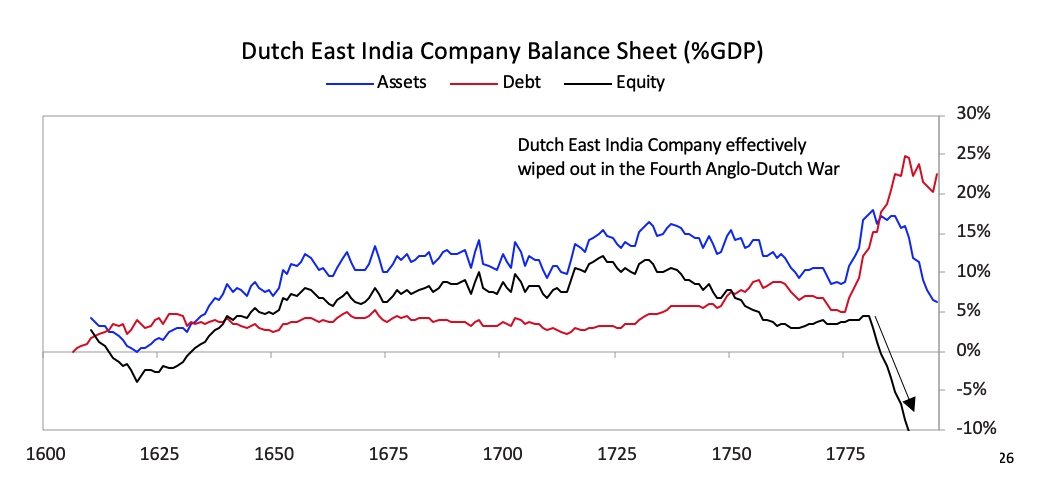

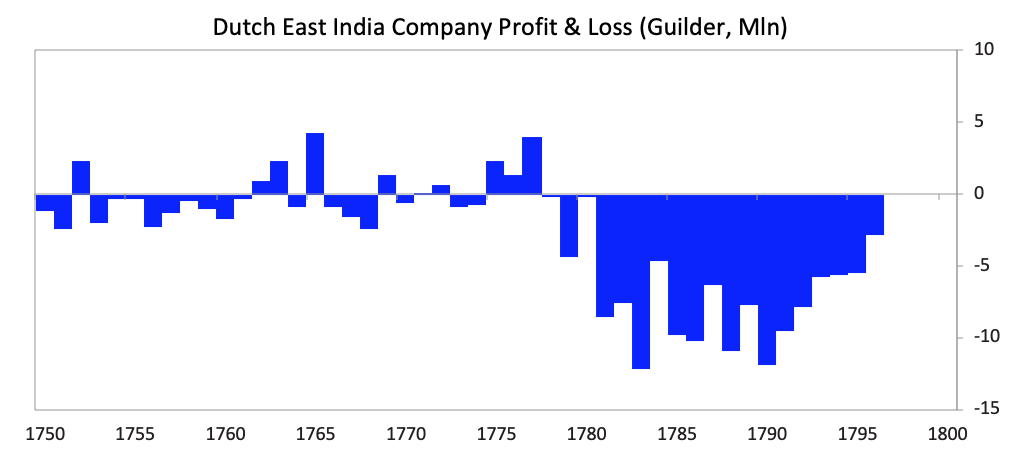

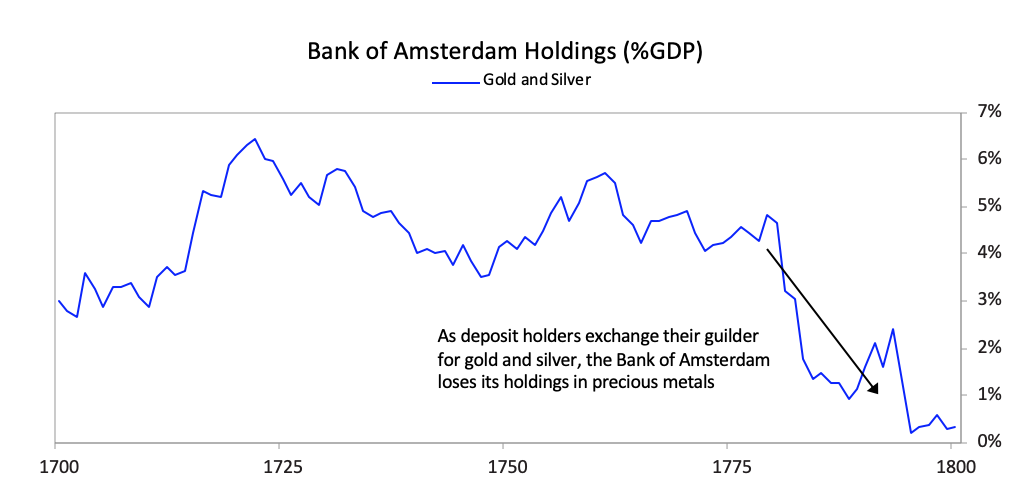

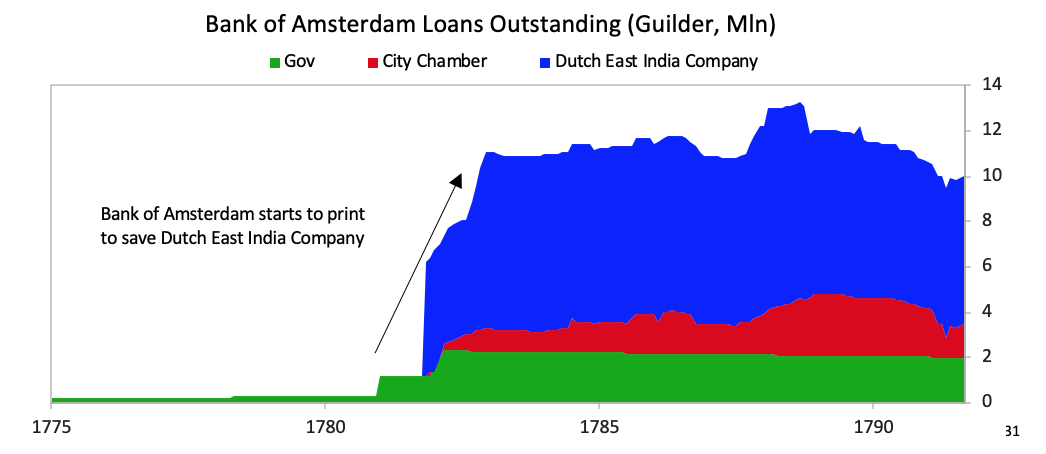

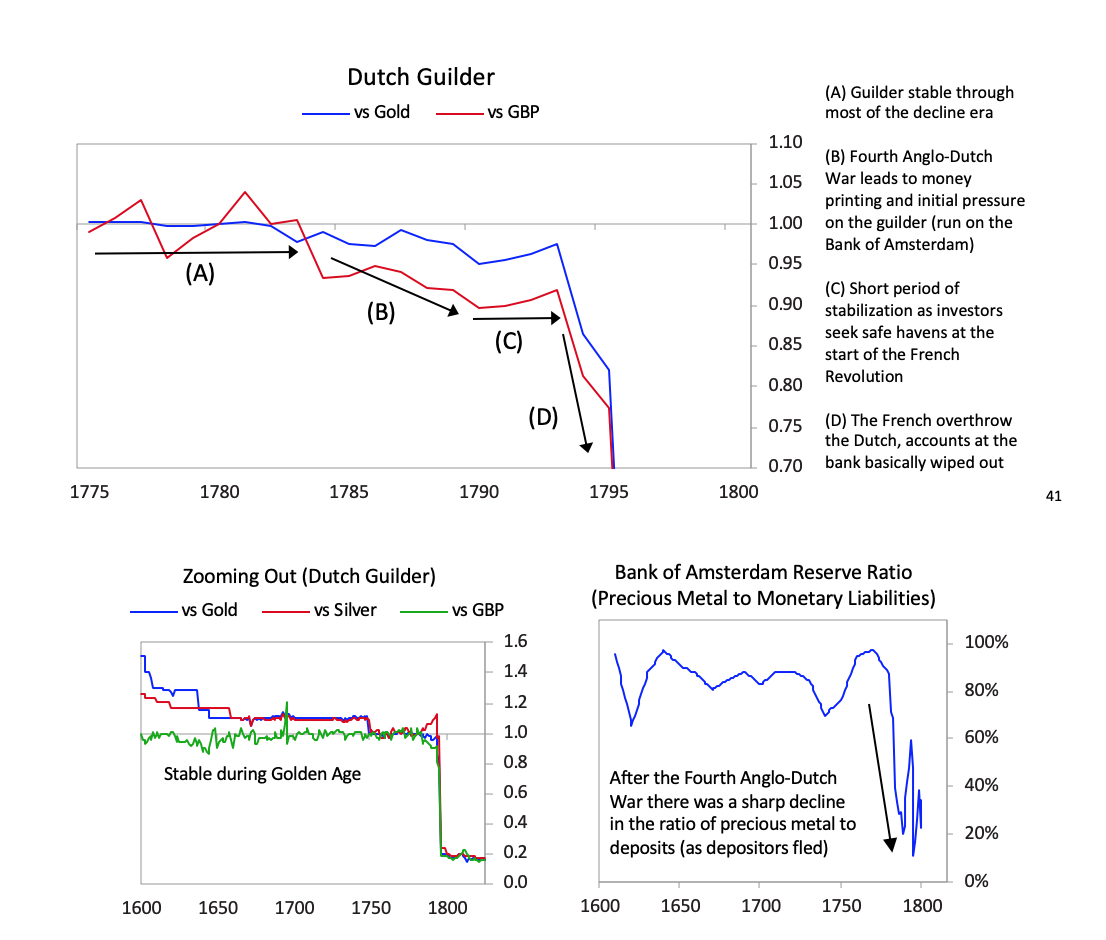

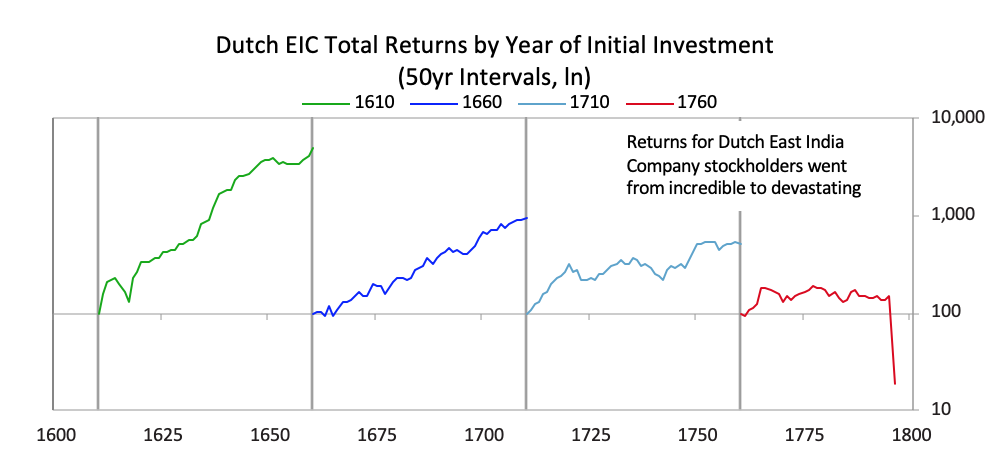

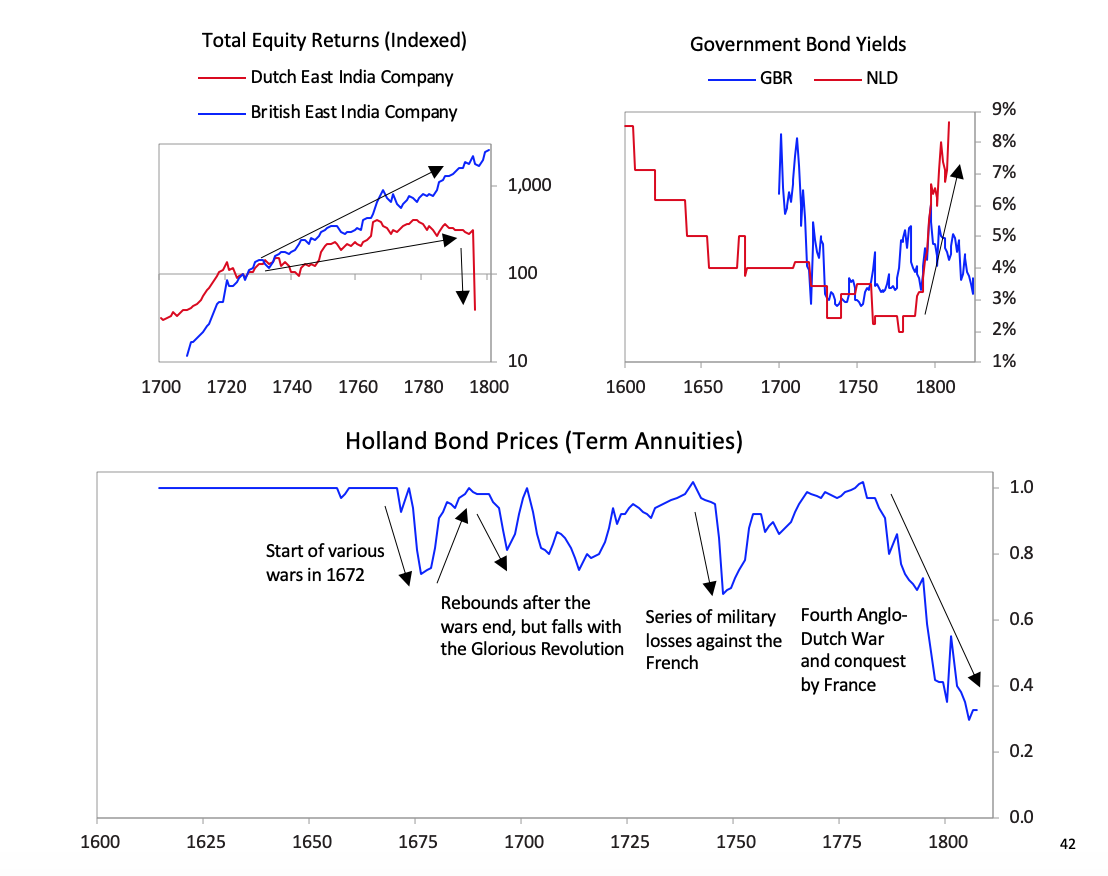

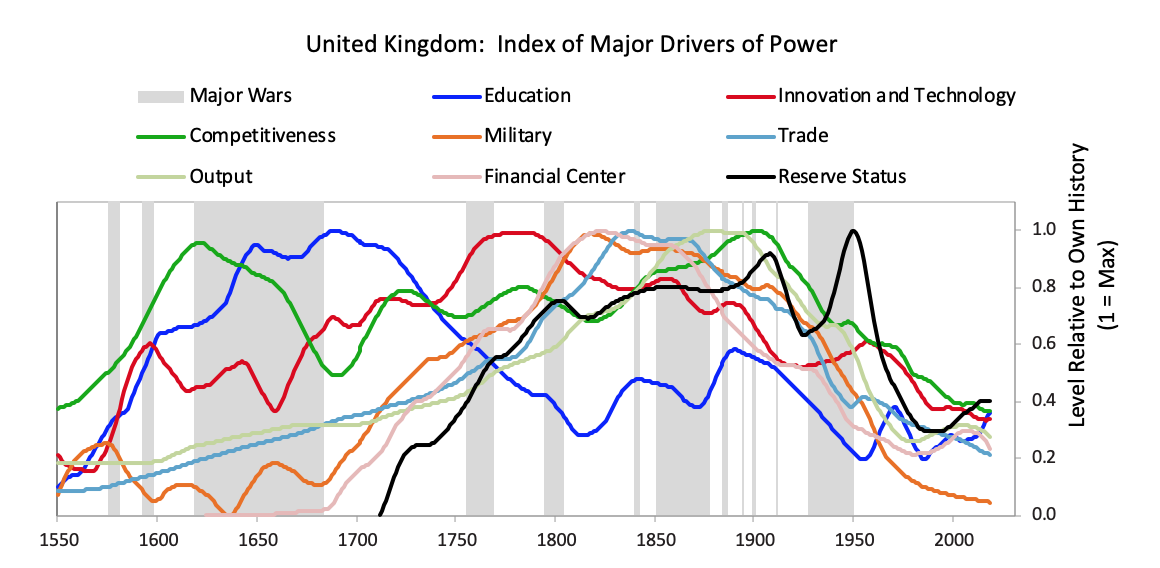

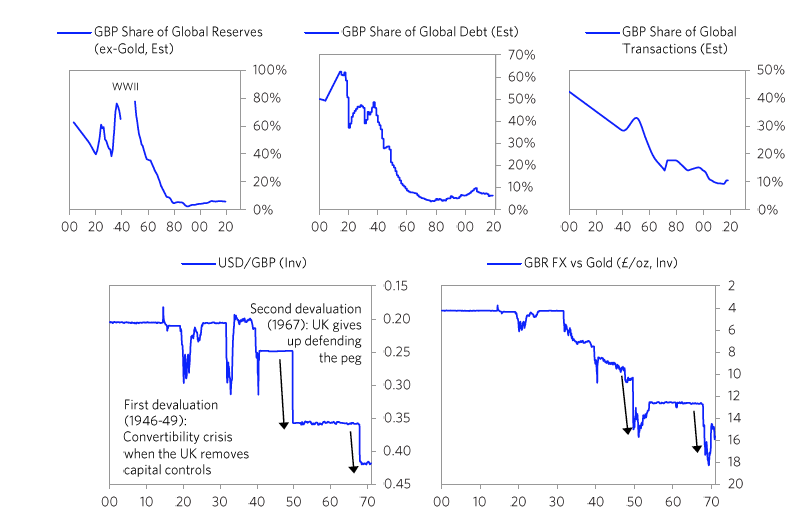

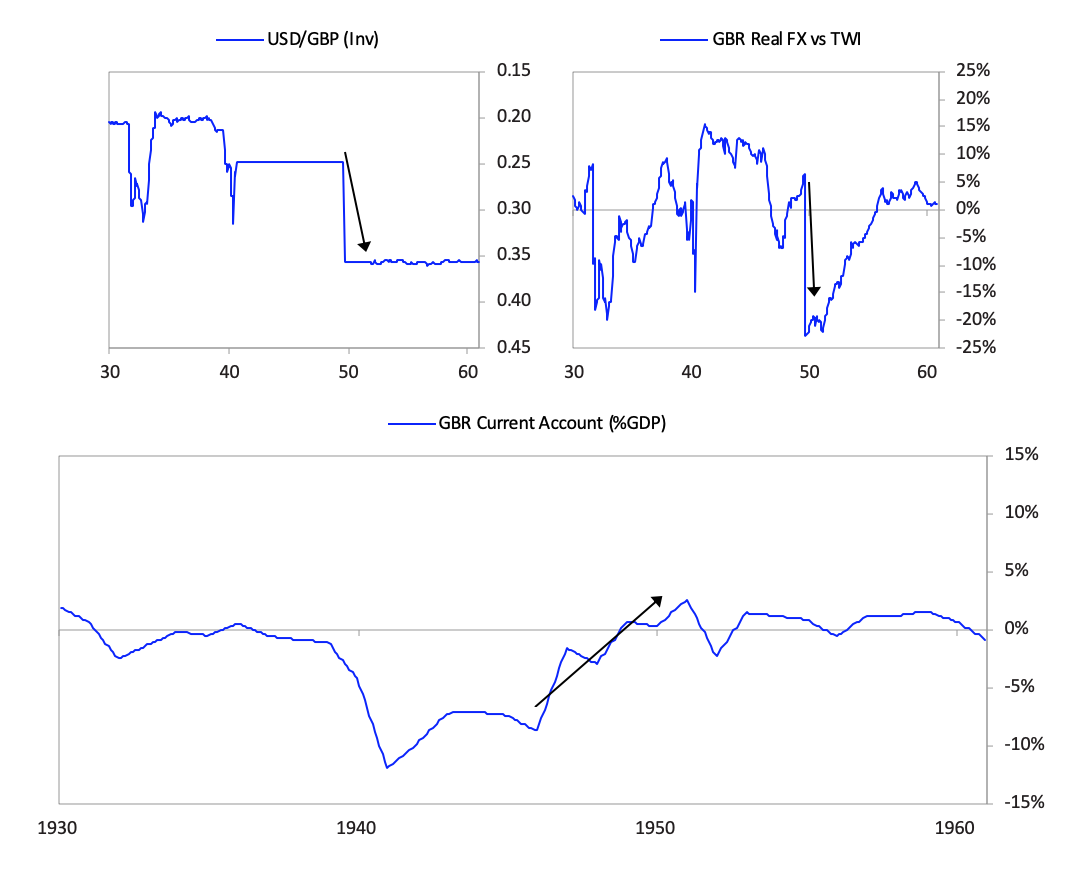

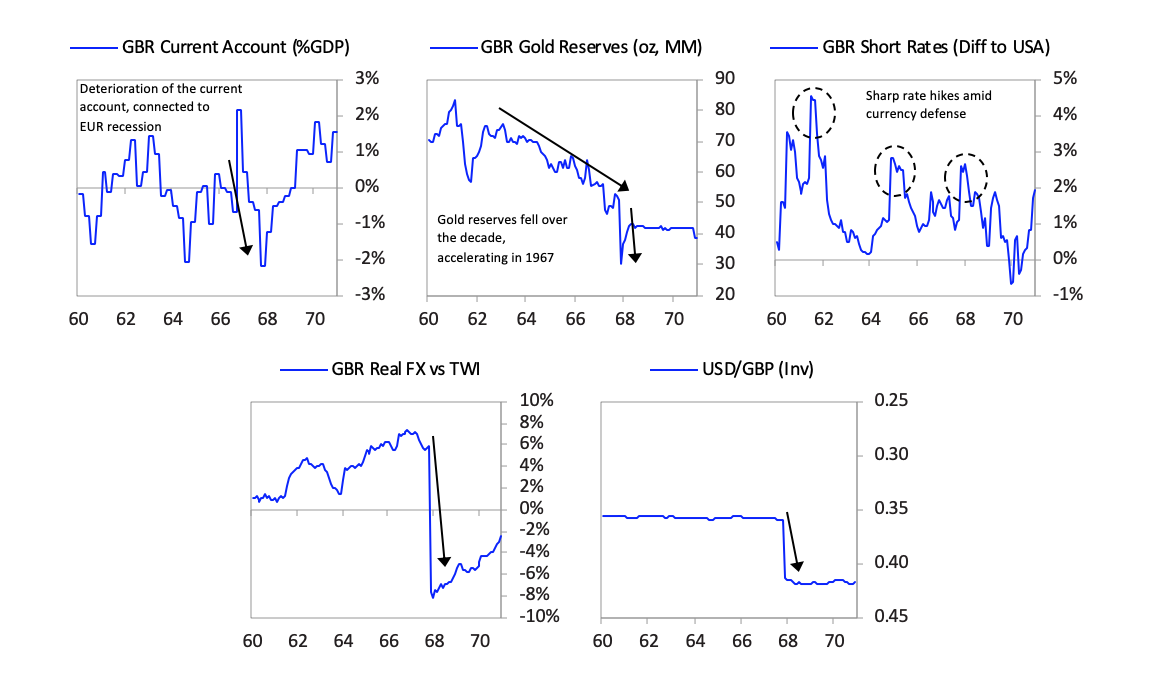

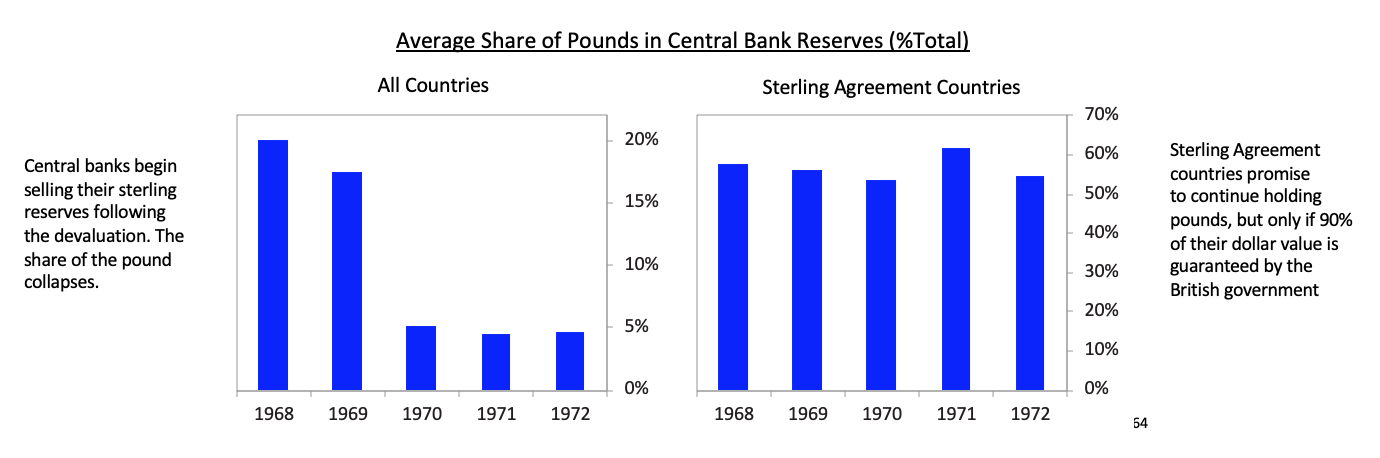

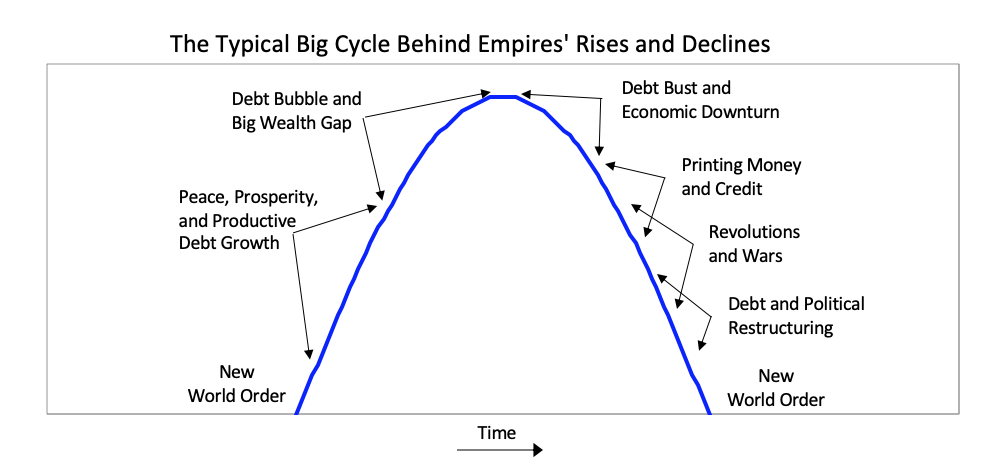

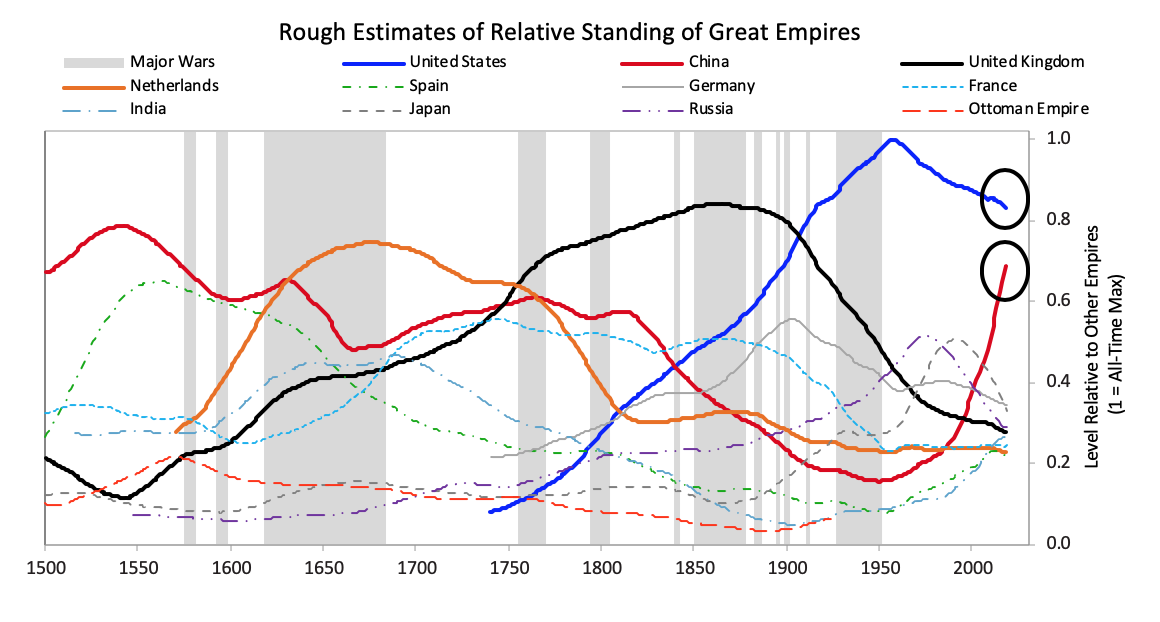

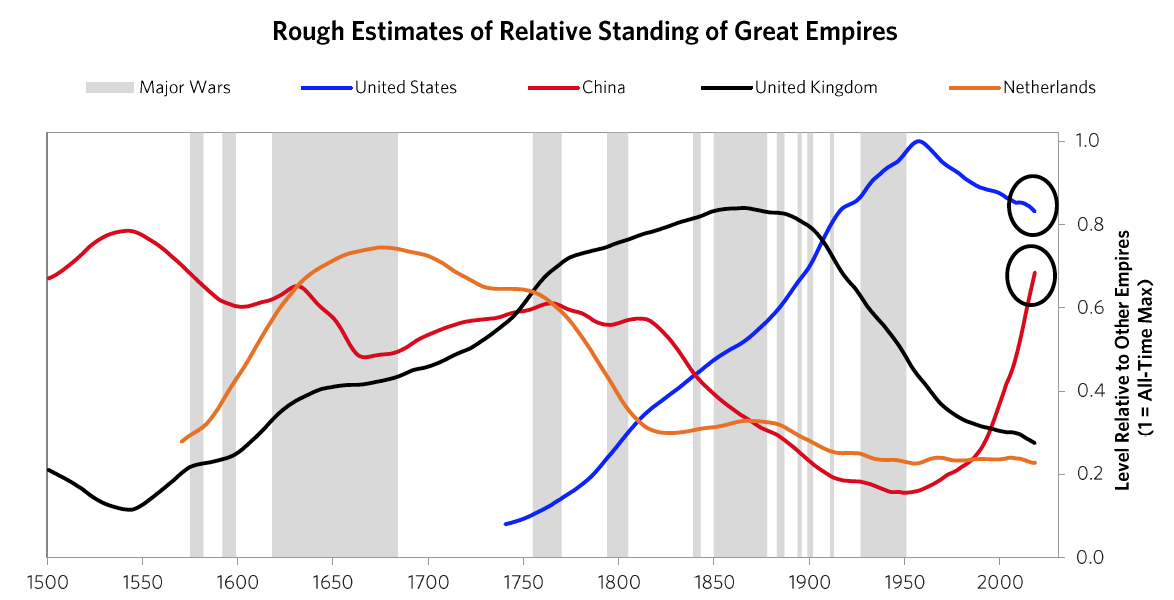

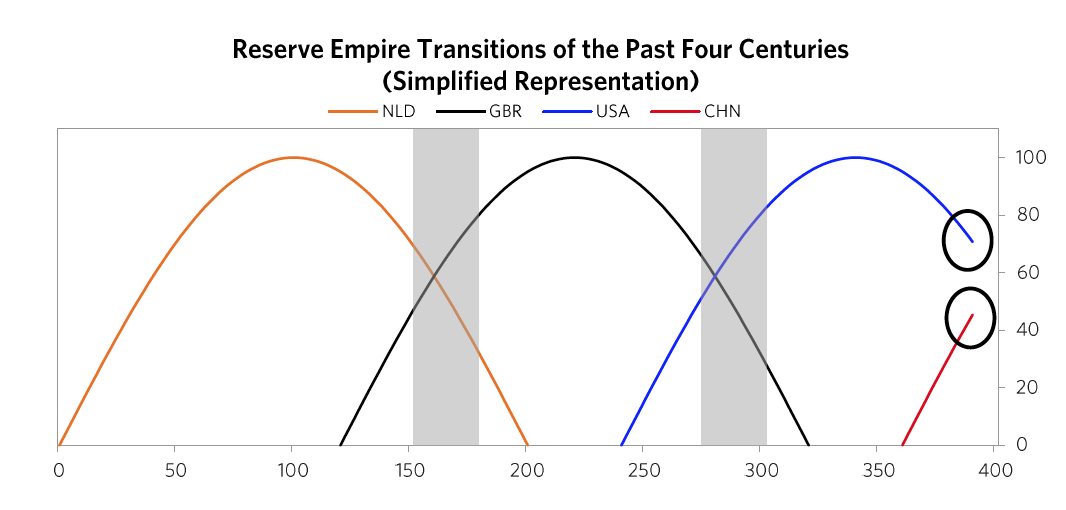

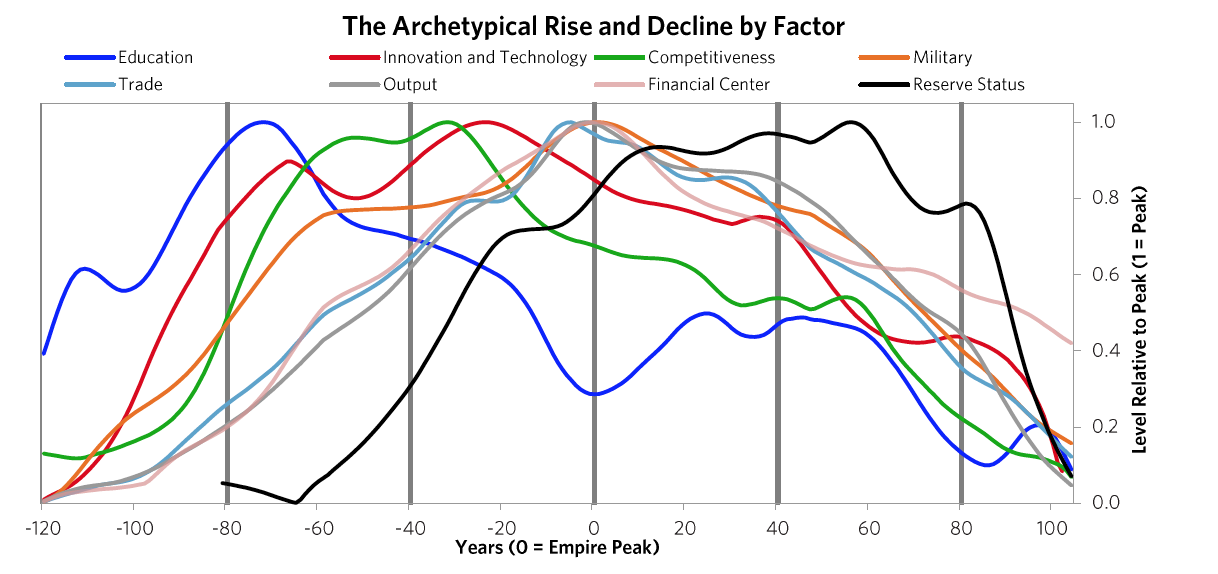

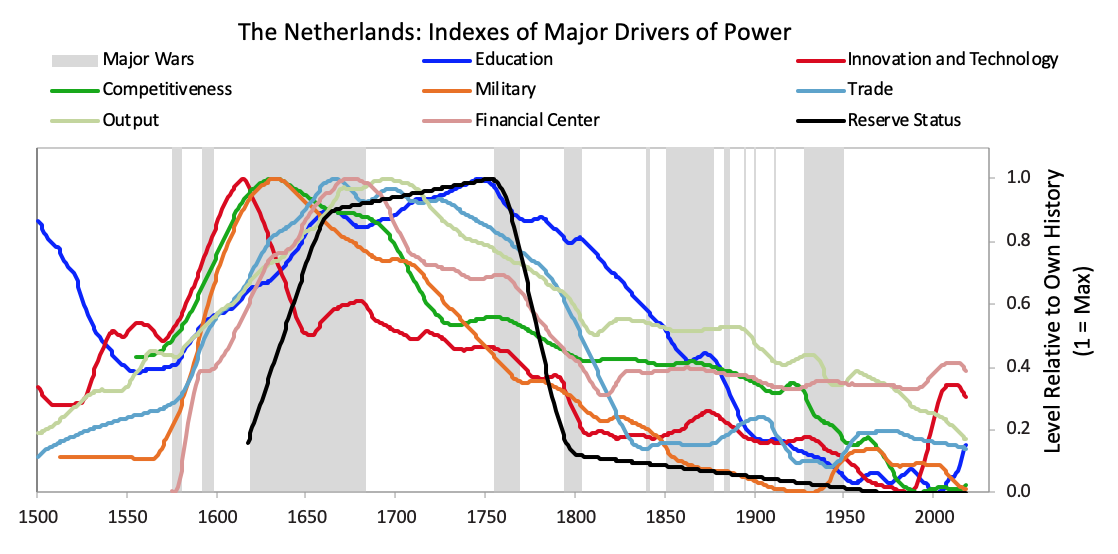

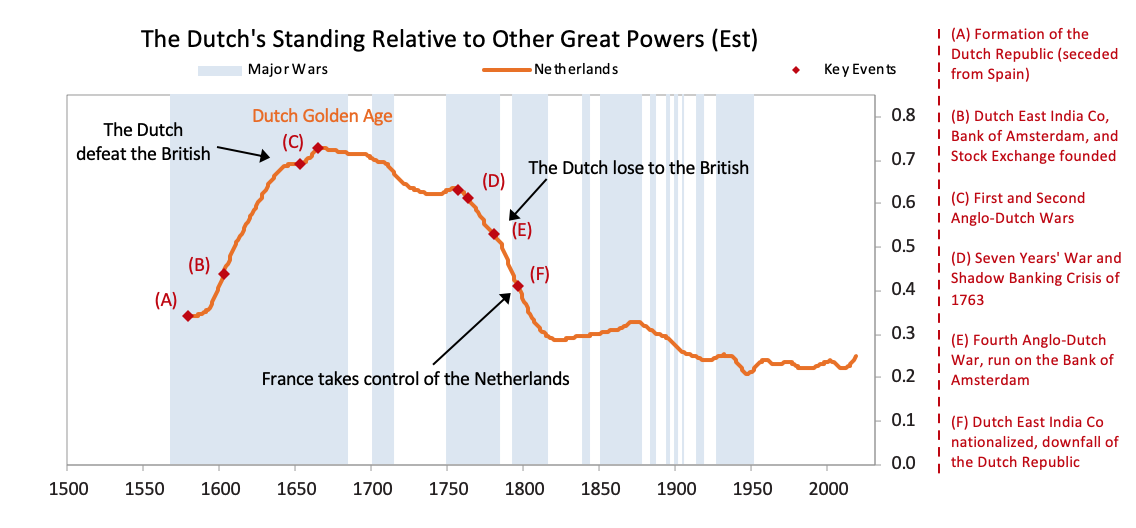

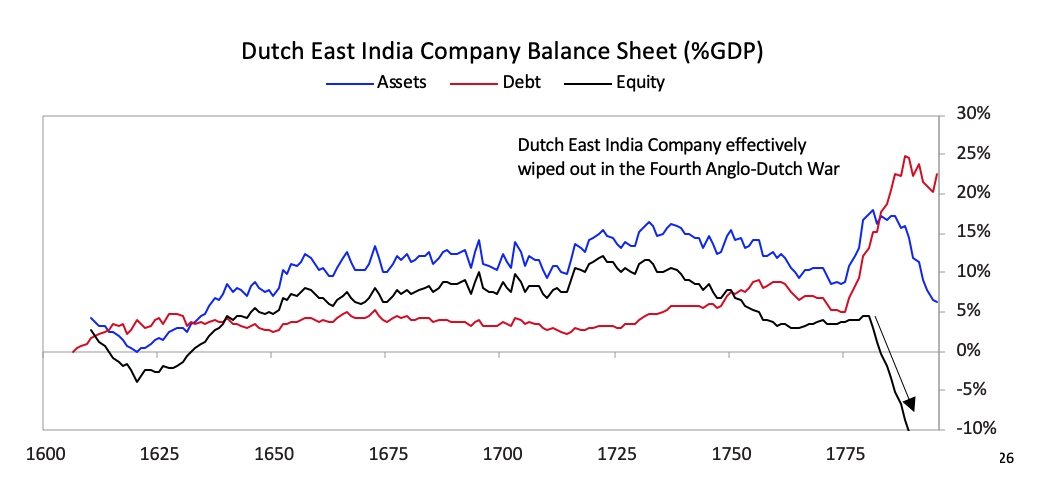

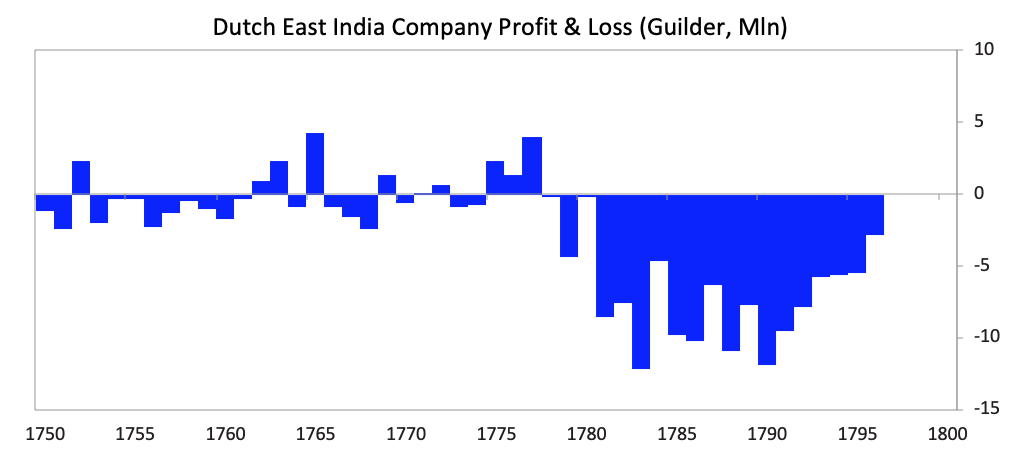

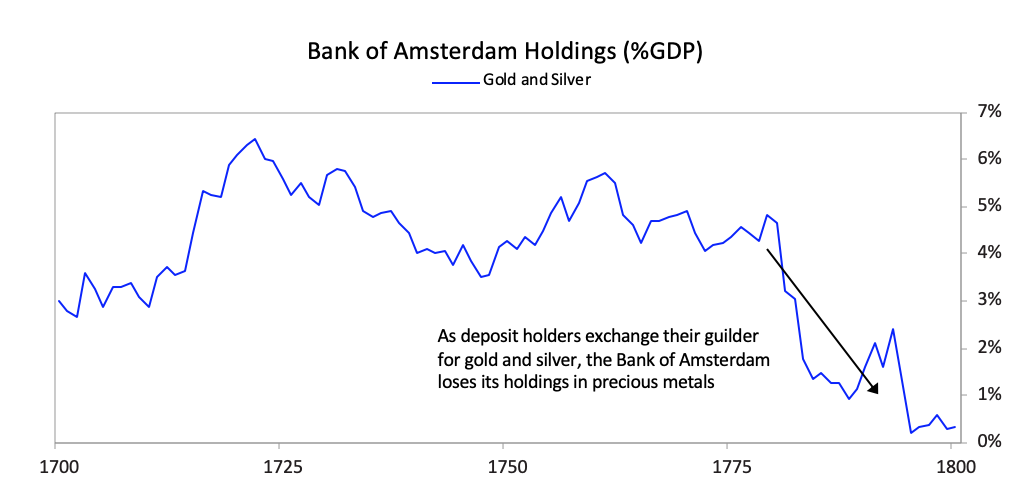

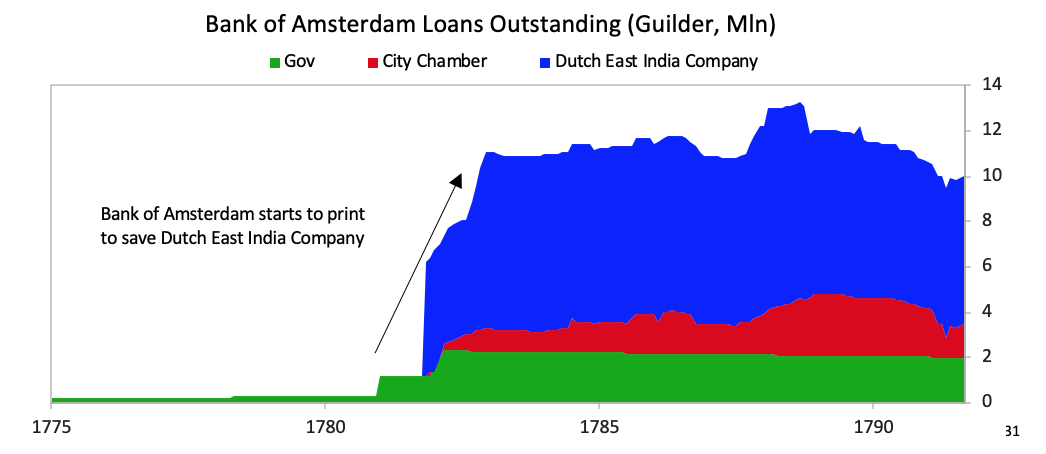

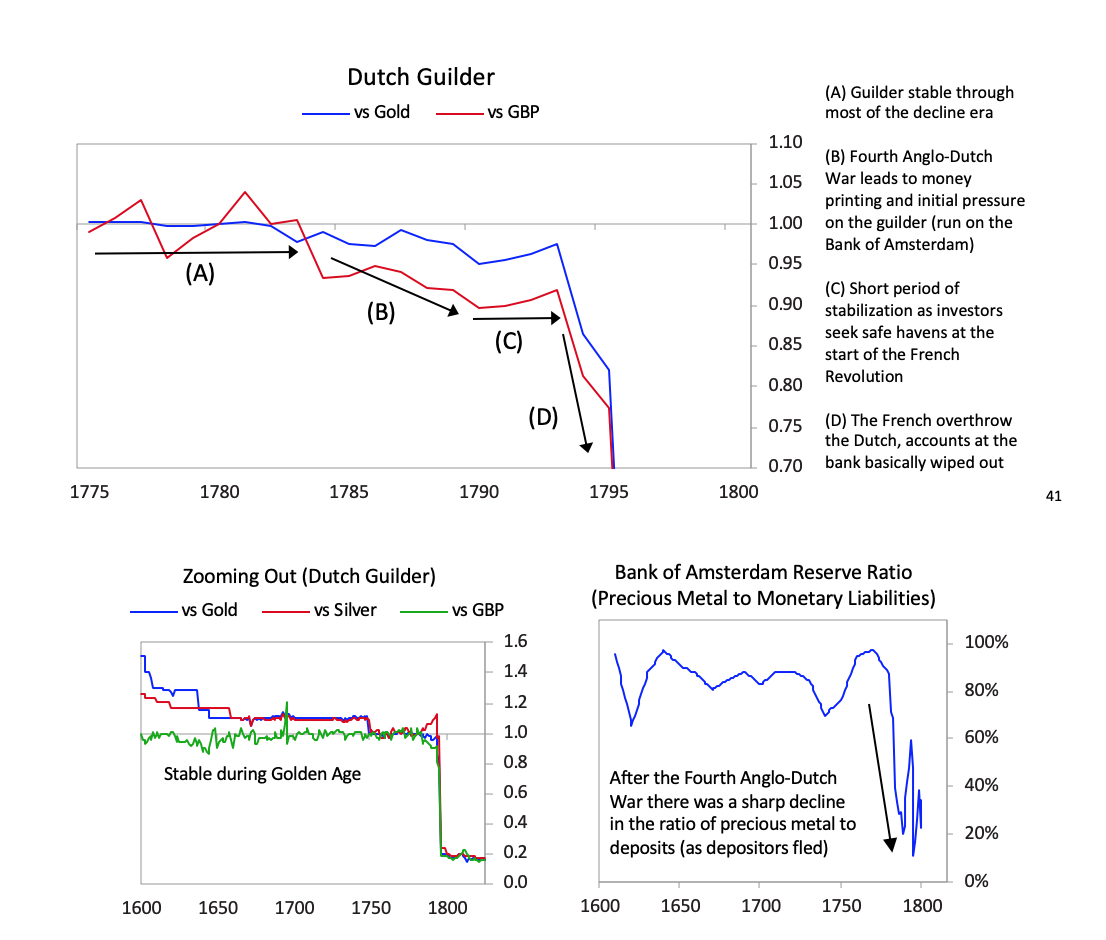

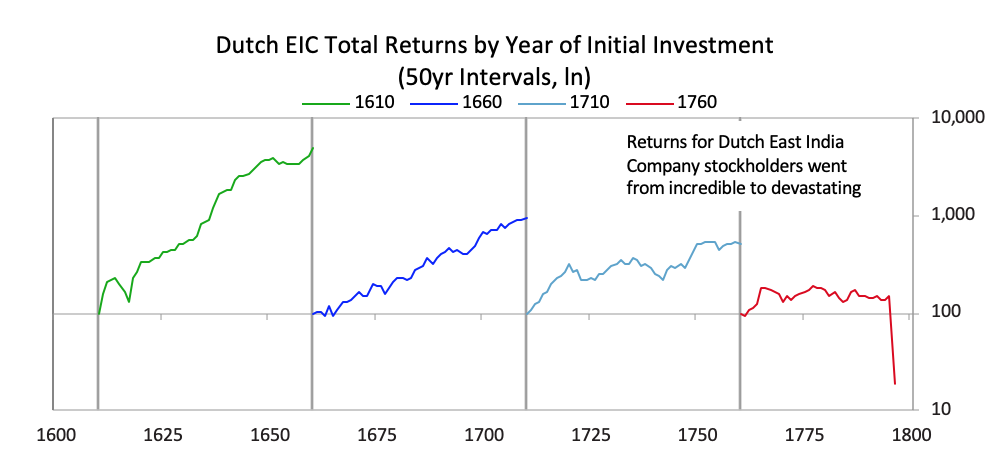

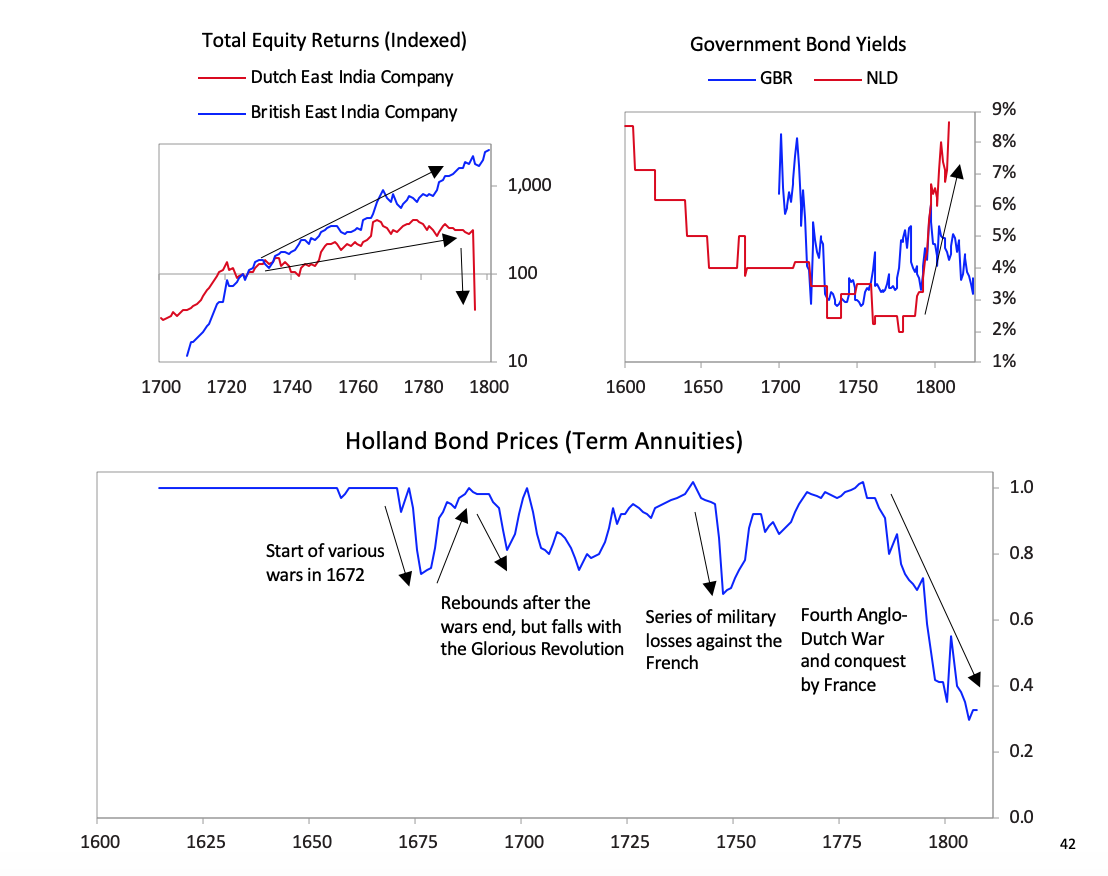

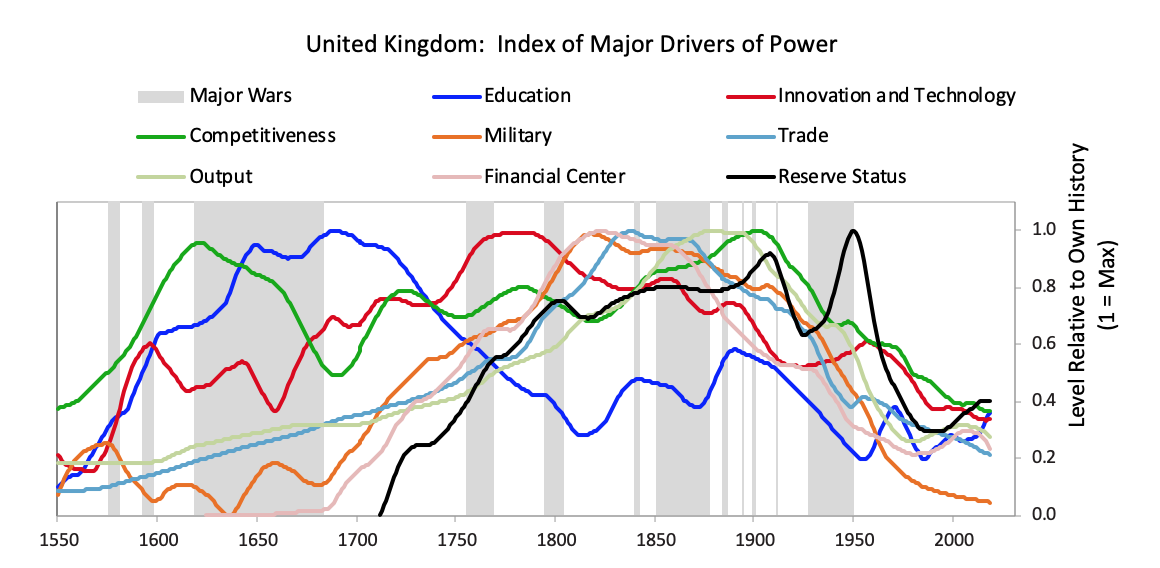

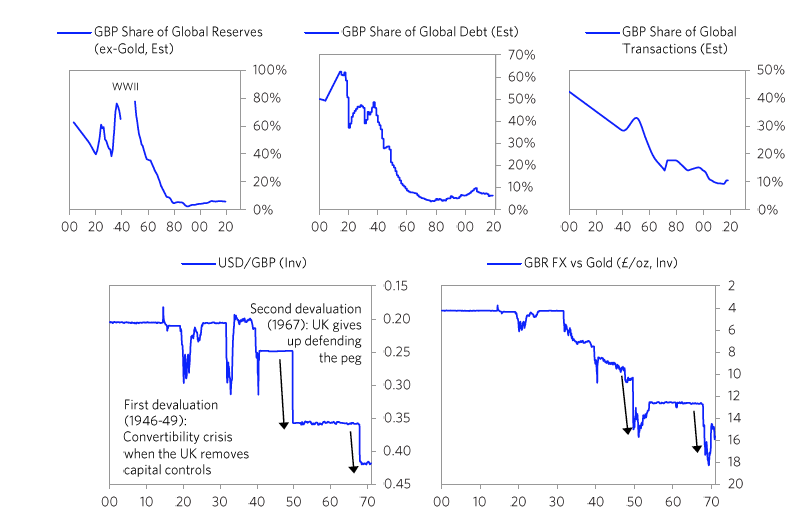

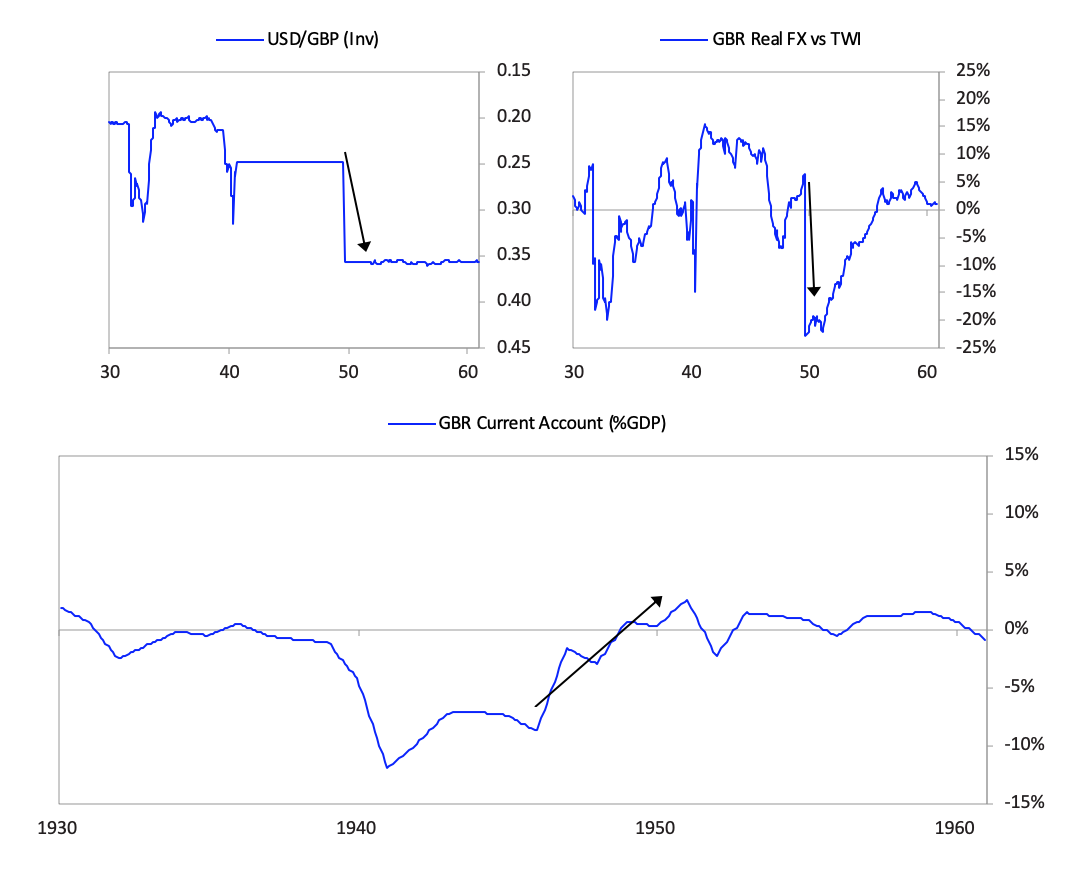

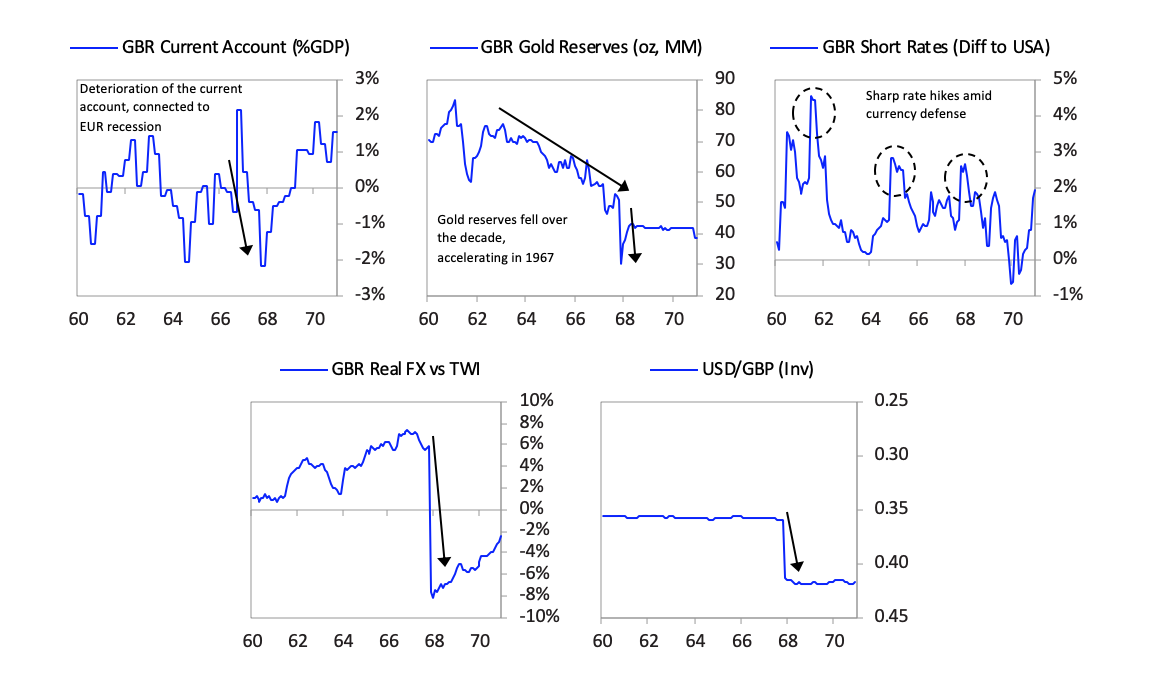

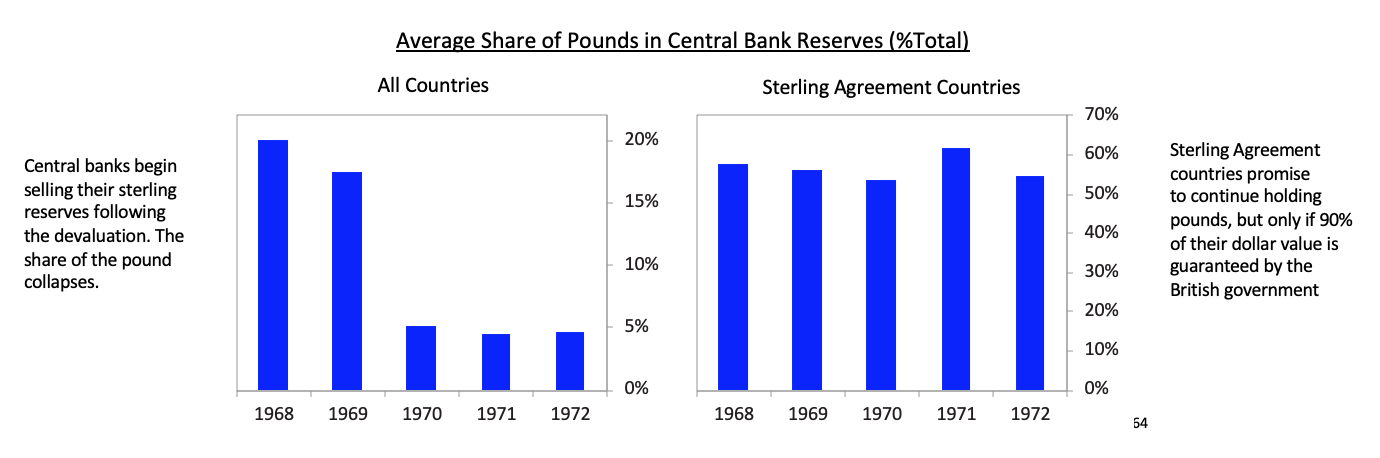

NEWSLETTER ON LINKEDIN Principled Perspectives By Ray DalioThe Big Cycles Over The Last 500 YearsNote: To make this an easier and shorter article to read, I tried to convey the most important points in simple language and bolded them, so you can get the gist of the whole thing in just a few minutes by focusing on what’s in bold. Past chapters from the series can be found here: Introduction, Chapter 1 and Chapter 2. Additionally, if you want a simple and entertaining 30-minute explanation of how what a lot of what I’m talking about here works, see “How the Economic Machine Works,” which is available on YouTube.In Chapter 1 (“The Big Picture in a Tiny Nutshell”), I looked at the archetypical rises and declines of empires and their reserve currencies and the various types of powers that they gained and lost, and in Chapter 2 (“The Big Cycle of Money, Credit, Debt, and Economic Activity”) and its appendix (“The Changing Value of Money”) I reviewed the big money, credit, and debt cycles. In this chapter, I will review the rises and declines of the Dutch, British, and American empires and their reserve currencies and will touch on the rise of the Chinese empire. While the evolution of empires and currencies is one continuous story that started before there was recorded history, in this chapter I am going to pick up the story around the year 1600. My objective is simply to put where we are in perspective of history and bring us up to date. I will begin by very briefly reviewing what the Big Cycle looks like and then scan through the last 500 years to show these Big Cycles playing out before examining more closely the declines of the Dutch and British empires and their reserve currencies. Then I will show how the decline of the British empire and the pound evolved into the rise of the US empire and US dollar and I will take a glimpse at the emergence of the Chinese empire and the Chinese renminbi.That will bring us up to the present and prepare us to try to think about what will come next. The Big Cycle of the Life of an EmpireJust as there is a human life cycle that typically lasts about 80 years (give or take) and no two are exactly the same but most are similar, there is an analogous empire life cycle that has its own typical patterns. For example, for most of us, during the first phase of life we are under our parents’ guidance and learn in school until we are about 18-24, at which point we enter the second phase. In this phase we work, become parents, and take care of others who are trying to be successful. We do this until we are about 55-65, at which time we enter the third phase when we become free of obligations and eventually die. It is pretty easy to tell what phases people are in because of obvious markers, and it is sensible for them to know what stages they are in and to behave appropriately in dealing with themselves and with others based on that. The same thing is true for countries. The major phases are shown on this chart. It’s the ultra-simplified archetypical Big Cycle that I shared in the last chapter.  In brief, after the creation of a new set of rules establishes the new world order, there is typically a peaceful and prosperous period. As people get used to this they increasingly bet on the prosperity continuing, and they increasingly borrow money to do that, which eventually leads to a bubble. As the prosperity increases the wealth gap grows. Eventually the debt bubble bursts, which leads to the printing of money and credit and increased internal conflict, which leads to some sort of wealth redistribution revolution that can be peaceful or violent. Typically at that time late in the cycle the leading empire that won the last economic and geopolitical war is less powerful relative to rival powers that prospered during the prosperous period, and with the bad economic conditions and the disagreements between powers there is typically some kind of war. Out of these debt, economic, domestic, and world-order breakdowns that take the forms of revolutions and wars come new winners and losers. Then the winners get together to create the new domestic and world orders. That is what has repeatedly happened through time. The lines in the chart signify the relative powers of the 11 most powerful empires over the last 500 years. In the chart below you can see where the US and China are currently in their cycles. As you can see the United States is now the most powerful empire by not much, it is in relative decline, Chinese power is rapidly rising, and no other powers come close. In brief, after the creation of a new set of rules establishes the new world order, there is typically a peaceful and prosperous period. As people get used to this they increasingly bet on the prosperity continuing, and they increasingly borrow money to do that, which eventually leads to a bubble. As the prosperity increases the wealth gap grows. Eventually the debt bubble bursts, which leads to the printing of money and credit and increased internal conflict, which leads to some sort of wealth redistribution revolution that can be peaceful or violent. Typically at that time late in the cycle the leading empire that won the last economic and geopolitical war is less powerful relative to rival powers that prospered during the prosperous period, and with the bad economic conditions and the disagreements between powers there is typically some kind of war. Out of these debt, economic, domestic, and world-order breakdowns that take the forms of revolutions and wars come new winners and losers. Then the winners get together to create the new domestic and world orders. That is what has repeatedly happened through time. The lines in the chart signify the relative powers of the 11 most powerful empires over the last 500 years. In the chart below you can see where the US and China are currently in their cycles. As you can see the United States is now the most powerful empire by not much, it is in relative decline, Chinese power is rapidly rising, and no other powers come close.  Because that chart is a bit confusing, for simplicity the next chart shows the same lines as in that chart except for just the most powerful reserve currency empires (which are based on an average of eight different measures of power that we explained in Chapter 1 and will explore more carefully in this chapter). Because that chart is a bit confusing, for simplicity the next chart shows the same lines as in that chart except for just the most powerful reserve currency empires (which are based on an average of eight different measures of power that we explained in Chapter 1 and will explore more carefully in this chapter). The next chart offers an even more simplified view. As shown, the United States and China are the only two major powers, you can see where each of their Big Cycles is, and you can see that they are approaching comparability, which is when the risks of wars of one type or another are greater than when the leading powers are earlier in the cycle. To be clear, I didn’t start out trying to make an argument and then go looking for stats to support it; doing that doesn’t work in my profession as only accuracy pays. I simply gathered stats that reflected these different measures of strength and put them in these indices, which led to these results. I suspect that if you did that exercise yourself picking whatever stats you’d like you’d see a similar picture, and I suspect that what I’m showing you here rings true to you if you’re paying attention to such things. For those reasons I suspect that all I am doing is helping you put where we are in perspective. To reiterate, I am not saying anything about the future. I will do that in the concluding chapter of this book. All I want to do is bring you up to date and, in the process, make clear how these cycles have worked in the past, which will also alert you to the markers to watch out for and help you see where in the cycles the major countries are and what is likely to come next. The next chart offers an even more simplified view. As shown, the United States and China are the only two major powers, you can see where each of their Big Cycles is, and you can see that they are approaching comparability, which is when the risks of wars of one type or another are greater than when the leading powers are earlier in the cycle. To be clear, I didn’t start out trying to make an argument and then go looking for stats to support it; doing that doesn’t work in my profession as only accuracy pays. I simply gathered stats that reflected these different measures of strength and put them in these indices, which led to these results. I suspect that if you did that exercise yourself picking whatever stats you’d like you’d see a similar picture, and I suspect that what I’m showing you here rings true to you if you’re paying attention to such things. For those reasons I suspect that all I am doing is helping you put where we are in perspective. To reiterate, I am not saying anything about the future. I will do that in the concluding chapter of this book. All I want to do is bring you up to date and, in the process, make clear how these cycles have worked in the past, which will also alert you to the markers to watch out for and help you see where in the cycles the major countries are and what is likely to come next. The chart below from Chapter 1 shows this play out via the eight measures of strength—education, innovation and technology, competitiveness, military, trade, output, financial center, and reserve status—that we capture in the aggregate charts. It shows the average of each of these measures of strength, with most of the weight on the most recent three reserve countries (the US, the UK, and the Dutch).[1] The chart below from Chapter 1 shows this play out via the eight measures of strength—education, innovation and technology, competitiveness, military, trade, output, financial center, and reserve status—that we capture in the aggregate charts. It shows the average of each of these measures of strength, with most of the weight on the most recent three reserve countries (the US, the UK, and the Dutch).[1]  As explained in Chapter 1, in brief these strengths and weaknesses are mutually reinforcing—i.e., strengths and weaknesses in education, competitiveness, economic output, share of world trade, etc., contribute to the others being strong or weak, for logical reasons—and their order is broadly indicative of the processes that lead to the rising and declining of empires. For example, quality of education has been the long-leading strength of rises and declines in these measures of power, and the long-lagging strength has been the reserve currency. That is because strong education leads to strengths in most areas, including the creation of the world’s most common currency. That common currency, just like the world’s common language, tends to stay around because the habit of usage lasts longer than the strengths that made it so commonly used. We will now look at the specifics more closely, starting with how these Big Cycles have played out over the last 500 years and then looking at the declines of the Dutch and British empires so you can see how these things go.1) The Last 500 Years in About 4,000 Words The Rise & Decline of the Dutch Empire and the Dutch Guilder In the 1500-1600 period the Spanish empire was the pre-eminent economic empire in the “Western” world while the Chinese empire under the Ming Dynasty was the most powerful empire in the “Eastern” world, even more powerful than the Spanish empire (see the green dashed line and the red solid line in chart 2). The Spanish got rich by taking their ships and military power around the world, seizing control of vast areas (13% of the landmass of the earth!) and extracting valuable things from them, most importantly gold and silver which were the money of the time. As shown by the orange line in the chart of the relative standing of the great empires, the Dutch gained power as Spanish power was waning. At the time Spain controlled the small area we now call Holland. When the Dutch became powerful enough in 1581, they overthrew the Spanish and went on to eclipse both the Spanish and the Chinese as the world’s richest empire from around 1625 to their collapse in 1780. The Dutch empire reached its peak around 1650 in what was called the Dutch Golden Age. This period was one of great globalization as ships that could travel around the world to gain the riches that were out there flourished, and the Dutch, with their great shipbuilding and their economic system, were ahead of others in using ships, economic rewards, and military power to build their empire. Holland (as we now call it) remained the richest power for about 100 years. How did that happen?The Dutch were superbly educated people who were very inventive—in fact they came up with 25% of all major inventions in the world at their peak in the 17th century. The two most important inventions they came up with were 1) ships that were uniquely good that could take them all around the world, which, with the military skills that they acquired from all the fighting they did in Europe, allowed them to collect great riches around the world, and 2) the capitalism that fueled these endeavors. Not only did the Dutch follow a capitalist approach to resource allocation, they invented capitalism. By capitalism I mean public debt and equity markets. Of course production existed before, but that is not capitalism, and of course trade existed before, but that is not capitalism, and of course private ownership existed before, but that is not capitalism. By capitalism I mean the ability of large numbers of people to collectively lend money and buy ownership in money-making endeavors. The Dutch created that when they invented the first listed public company (the Dutch East India Company) and the first stock exchange in 1602 and when they built the first well-developed lending system in which debt could more easily be created. They also created the world’s first reserve currency. The Dutch guilder was the first “world reserve currency” other than gold and silver because it was the first empire to extend around much of the world and to have its currency so broadly accepted. Fueled by these qualities and strengths, the Dutch empire continued to rise on a relative basis until around 1700 when the British started to grow strongly. The numerous investment market innovations of the Dutch and their successes in producing profits attracted investors, which led to Amsterdam becoming the world’s leading financial center; the Dutch government channeled money into debt and some equity investments in various businesses, the most important of which was the Dutch East India Company.At this time of prosperity, other countries grew in power too. As other countries became more competitive, the Dutch empire became more costly and less competitive, and it found maintaining its empire less profitable and more challenging. Most importantly the British got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. Before they had become clear competitors they had military partnerships during most of the 80+ years leading up to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. That changed over time as they bumped into each other in the same markets. The Dutch and British had lots of conflicts over economic issues. For example, the English made a law that only English ships could be used to import goods into England, which hurt Dutch shipping companies that had a big business of shipping others’ goods to England, which led to the English seizing Dutch ships and expanding the British East India Company. Typically before all-out war is declared there is about a decade of these sorts of economic, technological, geopolitical, and capital wars when the conflicting powers approach comparability and test and try to intimidate each other’s powers. At the time the British came up with military inventions and built more naval strength, and they continued to gain relative economic strength. As shown in the chart of relative standing of empires shown above, around 1750 the British became a stronger power than the Dutch, particularly economically and militarily, both because the British (and French) became stronger and because the Dutch became weaker. As is classic the Dutch a) became more indebted, b) had a lot of internal fighting over wealth (between its states/provinces, between the rich and the poor, and between political factions)[2], and c) had a weakened military—so the Dutch were weak and divided, which made them vulnerable to attack.As is typical, the rising great power challenged the existing leading power in a war to test them both economically and militarily. The English hurt the Dutch economically by hurting their shipping business with other countries. The British attacked the Dutch. Other competing countries, most importantly France, took this as an opportunity to grab shipping business from the Dutch. That war, known as the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, lasted from 1780 to 1784. The British won it handily both financially and militarily. That bankrupted the Dutch and caused Dutch debt and equities, the Dutch guilder, and the Dutch empire to collapse. In the next section we will look at that collapse up close. At that time, in the late 18th century, there was a lot of fighting between countries with various shifting alliances within Europe. While similar fights existed around the world as they nearly always do, the only reason I’m focusing on these fights is because I’m focusing just on the leading powers and these were the leading two. After the British defeated the Dutch, Great Britain and its allies (Austria, Prussia, and Russia) continued to fight the French led by Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. Finally, after around a quarter-century of frequent fighting since the start of the French Revolution, the British and its allies won in 1815. The Rise & Decline of the British Empire and the British PoundAs is typical after wars, the winning powers (most notably the UK, Russia, Austria, and Prussia) met to agree on the new world order. That meeting was called the Congress of Vienna. In it the winning powers re-engineered the debt, monetary, and geopolitical systems and created a new beginning as laid out in the Treaty of Paris. That set the stage for Great Britain’s 100-year-long “imperial century” during which Great Britain became the unrivaled world power, the British pound became the world’s dominant currency, and the world flourished. As is typical, following the period of war there was an extended period—in this case 100 years—of peace and prosperity because no country wanted to challenge the dominant world power and overturn the world order that was working so well. Of course during these 100 years of great prosperity there were bad economic periods along the lines of what we call recessions and which used to be called panics (e.g., the Panic of 1825 in the UK, or the Panics of 1837 and 1873 in the US) and there were military conflicts (e.g., the Crimean War between Russia on one side and the Ottoman empire with a coalition of Western European powers as allies on the other), but they were not significant enough to change the big picture of this being a very prosperous and peaceful period with the British on top. Like the Dutch before them, the British followed a capitalist system to incentivize and finance people to work collectively, and they combined these commercial operations with military strength to exploit global opportunities in order to become extremely wealthy and powerful. For example the British East India Company replaced the Dutch East India Company as the world’s most economically dominant company and the company’s military force became about twice the size of the British government’s standing military force. That approach made the British East India Company extremely powerful and the British people very rich and powerful. Additionally, at the same time, around 1760, the British created a whole new way of making things and becoming rich while raising people’s living standards. It was called the Industrial Revolution. It was through machine production, particularly propelled by the steam engine. So, this relatively small country of well-educated people became the world’s most powerful country by combining inventiveness, capitalism, great ships and other technologies that allowed them to go global, and a great military to create the British empire that was dominant for the next 100 years. Naturally London replaced Amsterdam as the world’s capital markets center and continued to innovate financial products. Later in that 100-year peaceful and prosperous period, from 1870 to the early 1900s the inventive and prosperous boom continued as the Second Industrial Revolution. During it human ingenuity created enormous technological advances that raised living standards and made those who developed them and owned them rich. This period was for Great Britain what “the Dutch Golden Age” was for the Dutch about 200 years earlier because it raised the power in all the eight key ways—via excellent education, new inventions and technologies, stronger competitiveness, higher output and trade, a stronger military and financial center, and a more widely used reserve currency.At this time several other countries used this period of relative peace and prosperity to get richer and stronger by colonizing enormous swaths of the world. As is typical during this phase, other countries copied Britain’s technologies and techniques and flourished themselves, producing prosperity and, with it, great wealth gaps. For example, during this period there was the invention of steel production, the development of the automobile, and the development of electricity and its applications such as for communications including Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb and phonograph. This is when the United States grew strongly to become a leading world power. These countries became very rich and their wealth gaps increased. That period was called “the Gilded Age” in the US, “la Belle Époque” in France, and “the Victorian Era” in England. As is typical at such times the leading power, Great Britain, became more indulgent while its relative power declined, and it started to borrow excessively.As other countries became more competitive, the British empire became more costly and less profitable to maintain. Most importantly other European countries and the US got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. As shown in the chart of the standing of empires above, the US became a comparable power economically and militarily around 1900 though the UK retained stronger military power, trade, and reserve currency status, and the US continued to gain relative strength from there.From 1900 until 1914, as a consequence of the large wealth gaps, there became 1) greater arguments about how wealth should be divided within countries and 2) greater conflicts and comparabilities in economic and military powers that existed between European countries. As is typical at such times the international conflicts led to alliances being formed and eventually led to war. Before the war the conflicts and the alliances were built around money and power considerations. For example, typical of conflicting powers that seek to cut off their enemies’ access to money and credit, Germany under Bismarck refused to let Russia sell its bonds in Berlin, which led them to be sold in Paris, which reinforced the French-Russian alliance. The wealth gap in Russia led it to tumble into revolution in 1917 and out of the war, which is a whole other dramatic story about fighting over wealth and power that is examined in Part 2 of this book. Similar to the economically motivated shipping conflict between the British and the Dutch, Germany sank five merchant ships that were going to England in the first years of the war. That brought the United States into the war. Frankly, the complexities of the situations leading up to World War I are mind-boggling, widely debated among historians, and way beyond me. That war, which was really the first world war because it involved countries all around the world because the world had become global, lasted from 1914 until 1918 and cost the lives of an estimated 8.5 million soldiers and 13 million civilians. As it ended, the Spanish flu arrived, killing an estimated 20-50 million people over two years. So 1914-20 was a terrible time. The Rise of the American Empire and the US Dollar After World War I[3]As is typical after wars, the winning powers—in this case the US, Britain, France, Japan, and Italy—met to set out the new world order. That meeting, called the Paris Peace Conference, took place in early 1919, lasted for six months, and concluded with the Treaty of Versailles. In that treaty the territories of the losing powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman empire, and Bulgaria) were carved up and put under the controls of the winning empires and the losing powers were put deeply into debt to the winning powers to pay back the winning countries’ war costs with these debts payable in gold. The United States was then clearly recognized as a leading power so it played a role in shaping the new world order. In fact the term “new world order” came about in reference to US President Woodrow Wilson’s vision for how countries would operate in pursuit of their collective interest through a global governance system (the League of Nations) which was a vision that quickly failed. After World War I the US chose to remain more isolationist while Britain continued to expand and oversee its global colonial empire. The monetary system in the immediate post-war period was in flux. While most countries endeavored to restore gold convertibility, currency stability against gold only came after a period of sharp devaluations and inflation.The large foreign debt burdens placed on Germany set the stage for 1) Germany’s post-war inflationary depression from 1920 to 1923 that wiped out the debts and was followed by Germany’s strong economic and military recovery, and 2) a decade of peace and prosperity elsewhere, which became the “Roaring ’20s.” During that time the United States also followed a classic capitalist approach to resource allocation and New York became a rival financial center to London, channeling debt and investments into various businesses. Other countries became more competitive and prosperous and increasingly challenged the leading powers. Most importantly Germany, Japan, and the US got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. However, the US was isolationist and didn’t have a big colonial empire past its borders so it was essentially out of the emerging conflict. As shown in the chart of the standing of empires above, Germany and Japan both gained in power relative to the UK during this interwar period, though the UK remained stronger. As is typical, the debts and the wealth gaps that were built up in the 1920s led to the debt bubbles that burst in 1929 which led to depressions, which led to the printing of money, which led to devaluations of currencies and greater internal and external conflicts over wealth and power in the 1930s. For example, in the United States and the UK, while there were redistributions of wealth and political power, capitalism and democracy were maintained, while in Germany, Japan, Italy, and Spain they were not maintained. Russia played a significant peripheral role in ways I won’t delve into. China at the time was weak, fragmented, and increasingly controlled by a rising and increasingly militaristic and nationalistic Japan. To make a long story short, the Japanese and Germans started to make territorial expansions in the early to mid-1930s, which led to wars in Europe and Asia in the late 1930s that ended in 1945. As is typical, before all-out wars were declared there was about a decade of economic, technological, geopolitical, and capital wars when the conflicting powers approached comparability and tested and tried to intimidate the other powers. While 1939 and 1941 are known as the official start of the wars in Europe and the Pacific, the wars really started about 10 years before that, as economic conflicts that were at first limited progressively grew into World War II. As Germany and Japan became more expansionist economic and military powers, they increasingly competed with the UK, US, and France for both resources and influence over territories. That brought about the second world war which, as usual, was won by the winning countries coming up with new technologies (the nuclear bomb, while the most important, was just one of the newly invented weapons). Over 20 million died directly in the military conflicts, and the total death count was still higher. So 1930-45, which was a period of depression and war, was a terrible time. The Rise of the American Empire and the US Dollar After World War IIAs is typical after wars, the winning powers—most importantly the US, Britain, and Russia—met to set out the new world order. While the Bretton Woods Conference, Yalta Conference, and Potsdam Conference were the most noteworthy, several other meetings occurred that shaped the new world order, which included carving up the world and redefining countries and areas of influence and establishing a new money and credit system. In this case, the world was divided into the US-controlled capitalist/democratic countries and Russia-controlled communist and autocratically controlled countries, each with their own monetary systems. Germany was split into pieces, with the United States, Great Britain, and France having control of the West and Russia having control of the East. Japan was under US control and China returned to a state of civil war, mostly about how to divide the wealth, which was between communists and capitalists (i.e., the Nationalists). Unlike after World War I when the United States chose to be relatively isolationist, after World War II the United States took the primary leadership role as it had most of the economic, geopolitical, and military responsibility. The US followed a capitalist system. The new monetary system of the US-led countries had the dollar linked to gold and had most other countries’ currencies tied to the dollar. This system was followed by over 40 countries. Because the US had around two-thirds of the world’s gold then and because the US was much more powerful economically and militarily than any other country, this monetary system has worked best and carried on until now. As for the other countries that were not part of this system—most importantly Russia and those countries that were brought into the Soviet Union and the satellite countries that the Soviets controlled—they were built on a much weaker foundation that eventually broke down. Unlike after World War I, when the losing countries were burdened with large debts, countries that were under US control, including the defeated countries, received massive financial aid from the US via the Marshall Plan. At the same time the currencies and debts of the losing countries were wiped out, with those holding them losing all of their wealth in them. Great Britain was left heavily indebted from its war borrowings and faced the gradual end of the colonial era which would lead to the unraveling of its empire which was becoming uneconomic to have.During this post-World War II period the United States, its allies, and the countries that were under its influence followed a classic capitalist-democratic approach to resource allocation. New York flourished as the world’s pre-eminent financial center, and a new big debt and capital markets cycle began. That produced what has thus far been a relatively peaceful and prosperous 75-year period that has brought us to today.As is typical of this peaceful and prosperous part of the cycle, in the 1950-70 period there was productive debt growth and equity market development that were essential for financing innovation and development early on. That eventually led to too much debt being required to finance both war and domestic needs—what was called “guns and butter.” The Vietnam War and the “War on Poverty” occurred in the US. Other countries also became overly indebted and the British indebtedness became over-leveraged which led to a number of currency devaluations, most importantly the breakdown of the Bretton Woods monetary system (though countries like the UK and Italy had already devalued prior to that time). Then in 1971, when it was apparent that the US didn’t have enough gold in the bank to meet the claims on gold that it had put out, the US defaulted on its promise to deliver gold for paper dollars which ended the Type 2 gold-backed monetary system, and the world moved to a fiat monetary system. As is typical, this fiat monetary system initially led to a wave of great dollar money and debt creation that led to a big wave of inflation that carried until 1980-82 and led to the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. It was followed by three other waves of debt-financed speculations, bubbles, and busts—1) the 1982 and 2000 money and credit expansion that produced a dot-com bubble that led to the 2000-01 recession, 2) the 2002-07 money and credit expansion that produced a real estate bubble that led to the 2008 Great Recession, and 3) the 2009-19 money and credit expansion that produced the investment bubble that preceded the COVID-19 downturn. Each of these cycles raised debt and non-debt obligations (e.g., for pensions and healthcare) to progressively higher levels and led the reserve currency central banks of the post-war allies to push interest rates to unprecedented low levels and to print unprecedented amounts of money. Also classically, the wealth, values, and political gaps widened within countries, which increases internal conflicts during economic downturns. That is where we now are. During this prosperous post-war period many countries became more competitive with the leading powers economically and militarily. The Soviet Union/Russia initially followed a communist resource allocation approach as did China and a number of other smaller countries. None of these countries became competitive following this approach. However, the Soviet Union did develop nuclear weapons to become militarily threatening and gradually a number of other countries followed in developing nuclear weapons. These weapons were never used because using them would produce mutually assured destruction. Because of its economic failures the Soviet Union/Russia could not afford to support a) its empire, b) its economy, and c) its military at the same time in the face of US President Ronald Reagan’s arms race spending. As a result the Soviet Union broke down in 1991 and abandoned communism. The breakdown of its money/credit/economic system was disastrous for it economically and geopolitically for most of the 1990s. In the 1980-95 period most communist countries abandoned classic communism and the world entered a very prosperous period of globalization and free-market capitalism. In China, Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 led Deng Xiaoping to a shift in economic policies to include capitalist elements including private ownership of large businesses, the development of debt and equities markets, great technological and commercial innovations, and even the flourishing of billionaire capitalists—all, however, under the strict control of the Communist Party. As a result of this shift and the simultaneous shift in the world to greater amounts of globalism China grew much stronger in most ways. For example, since I started visiting China in 1984, the education of its population has improved dramatically, the real per capita income has multiplied by 24, and it has become the largest country in the world in trade (exceeding the US share of world trade), a rival technology leader, the holder of the greatest foreign reserves assets in the world by a factor of over two, the largest lender/investor in the emerging world, the second most powerful military power, and a geopolitical rival of the United States. And it is growing in power at a significantly faster pace than the United States and other “developed countries.” At the same time, we are in a period of great inventiveness due to advanced information/data management and artificial intelligence supplementing human intelligence with the Americans and Chinese leading the way. As shown at the outset of Chapter 1, human adaptability and inventiveness has proven to be the greatest force in solving problems and creating advances. Also, because the world is richer and more skilled than ever before, there is a tremendous capacity to make the world better for more people than ever if people can work together to make the whole pie as big as possible and to divide it well. That brings us to where we now are. As you can see, all three of these rises and declines followed the classic script laid out in Chapter 1 and summarized in the charts at the beginning of this chapter, though each had its own particular turns and twists. Now let’s look at these cases, especially the declines, more closely.A Closer Look at the Rises and Declines of the Leading Empires Over the Last 500 YearsThe Dutch Empire and the Dutch GuilderBefore we get to the collapse of the Dutch empire and the Dutch guilder let’s take a quick look at the whole arc of its rise and decline. While I previously showed you the aggregated power index for the Dutch empire, the chart below shows the eight powers that make it up from the ascent around 1575 to the decline around 1780. In it, you can see the story behind the rise and decline. As explained in Chapter 1, in brief these strengths and weaknesses are mutually reinforcing—i.e., strengths and weaknesses in education, competitiveness, economic output, share of world trade, etc., contribute to the others being strong or weak, for logical reasons—and their order is broadly indicative of the processes that lead to the rising and declining of empires. For example, quality of education has been the long-leading strength of rises and declines in these measures of power, and the long-lagging strength has been the reserve currency. That is because strong education leads to strengths in most areas, including the creation of the world’s most common currency. That common currency, just like the world’s common language, tends to stay around because the habit of usage lasts longer than the strengths that made it so commonly used. We will now look at the specifics more closely, starting with how these Big Cycles have played out over the last 500 years and then looking at the declines of the Dutch and British empires so you can see how these things go.1) The Last 500 Years in About 4,000 Words The Rise & Decline of the Dutch Empire and the Dutch Guilder In the 1500-1600 period the Spanish empire was the pre-eminent economic empire in the “Western” world while the Chinese empire under the Ming Dynasty was the most powerful empire in the “Eastern” world, even more powerful than the Spanish empire (see the green dashed line and the red solid line in chart 2). The Spanish got rich by taking their ships and military power around the world, seizing control of vast areas (13% of the landmass of the earth!) and extracting valuable things from them, most importantly gold and silver which were the money of the time. As shown by the orange line in the chart of the relative standing of the great empires, the Dutch gained power as Spanish power was waning. At the time Spain controlled the small area we now call Holland. When the Dutch became powerful enough in 1581, they overthrew the Spanish and went on to eclipse both the Spanish and the Chinese as the world’s richest empire from around 1625 to their collapse in 1780. The Dutch empire reached its peak around 1650 in what was called the Dutch Golden Age. This period was one of great globalization as ships that could travel around the world to gain the riches that were out there flourished, and the Dutch, with their great shipbuilding and their economic system, were ahead of others in using ships, economic rewards, and military power to build their empire. Holland (as we now call it) remained the richest power for about 100 years. How did that happen?The Dutch were superbly educated people who were very inventive—in fact they came up with 25% of all major inventions in the world at their peak in the 17th century. The two most important inventions they came up with were 1) ships that were uniquely good that could take them all around the world, which, with the military skills that they acquired from all the fighting they did in Europe, allowed them to collect great riches around the world, and 2) the capitalism that fueled these endeavors. Not only did the Dutch follow a capitalist approach to resource allocation, they invented capitalism. By capitalism I mean public debt and equity markets. Of course production existed before, but that is not capitalism, and of course trade existed before, but that is not capitalism, and of course private ownership existed before, but that is not capitalism. By capitalism I mean the ability of large numbers of people to collectively lend money and buy ownership in money-making endeavors. The Dutch created that when they invented the first listed public company (the Dutch East India Company) and the first stock exchange in 1602 and when they built the first well-developed lending system in which debt could more easily be created. They also created the world’s first reserve currency. The Dutch guilder was the first “world reserve currency” other than gold and silver because it was the first empire to extend around much of the world and to have its currency so broadly accepted. Fueled by these qualities and strengths, the Dutch empire continued to rise on a relative basis until around 1700 when the British started to grow strongly. The numerous investment market innovations of the Dutch and their successes in producing profits attracted investors, which led to Amsterdam becoming the world’s leading financial center; the Dutch government channeled money into debt and some equity investments in various businesses, the most important of which was the Dutch East India Company.At this time of prosperity, other countries grew in power too. As other countries became more competitive, the Dutch empire became more costly and less competitive, and it found maintaining its empire less profitable and more challenging. Most importantly the British got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. Before they had become clear competitors they had military partnerships during most of the 80+ years leading up to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. That changed over time as they bumped into each other in the same markets. The Dutch and British had lots of conflicts over economic issues. For example, the English made a law that only English ships could be used to import goods into England, which hurt Dutch shipping companies that had a big business of shipping others’ goods to England, which led to the English seizing Dutch ships and expanding the British East India Company. Typically before all-out war is declared there is about a decade of these sorts of economic, technological, geopolitical, and capital wars when the conflicting powers approach comparability and test and try to intimidate each other’s powers. At the time the British came up with military inventions and built more naval strength, and they continued to gain relative economic strength. As shown in the chart of relative standing of empires shown above, around 1750 the British became a stronger power than the Dutch, particularly economically and militarily, both because the British (and French) became stronger and because the Dutch became weaker. As is classic the Dutch a) became more indebted, b) had a lot of internal fighting over wealth (between its states/provinces, between the rich and the poor, and between political factions)[2], and c) had a weakened military—so the Dutch were weak and divided, which made them vulnerable to attack.As is typical, the rising great power challenged the existing leading power in a war to test them both economically and militarily. The English hurt the Dutch economically by hurting their shipping business with other countries. The British attacked the Dutch. Other competing countries, most importantly France, took this as an opportunity to grab shipping business from the Dutch. That war, known as the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, lasted from 1780 to 1784. The British won it handily both financially and militarily. That bankrupted the Dutch and caused Dutch debt and equities, the Dutch guilder, and the Dutch empire to collapse. In the next section we will look at that collapse up close. At that time, in the late 18th century, there was a lot of fighting between countries with various shifting alliances within Europe. While similar fights existed around the world as they nearly always do, the only reason I’m focusing on these fights is because I’m focusing just on the leading powers and these were the leading two. After the British defeated the Dutch, Great Britain and its allies (Austria, Prussia, and Russia) continued to fight the French led by Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. Finally, after around a quarter-century of frequent fighting since the start of the French Revolution, the British and its allies won in 1815. The Rise & Decline of the British Empire and the British PoundAs is typical after wars, the winning powers (most notably the UK, Russia, Austria, and Prussia) met to agree on the new world order. That meeting was called the Congress of Vienna. In it the winning powers re-engineered the debt, monetary, and geopolitical systems and created a new beginning as laid out in the Treaty of Paris. That set the stage for Great Britain’s 100-year-long “imperial century” during which Great Britain became the unrivaled world power, the British pound became the world’s dominant currency, and the world flourished. As is typical, following the period of war there was an extended period—in this case 100 years—of peace and prosperity because no country wanted to challenge the dominant world power and overturn the world order that was working so well. Of course during these 100 years of great prosperity there were bad economic periods along the lines of what we call recessions and which used to be called panics (e.g., the Panic of 1825 in the UK, or the Panics of 1837 and 1873 in the US) and there were military conflicts (e.g., the Crimean War between Russia on one side and the Ottoman empire with a coalition of Western European powers as allies on the other), but they were not significant enough to change the big picture of this being a very prosperous and peaceful period with the British on top. Like the Dutch before them, the British followed a capitalist system to incentivize and finance people to work collectively, and they combined these commercial operations with military strength to exploit global opportunities in order to become extremely wealthy and powerful. For example the British East India Company replaced the Dutch East India Company as the world’s most economically dominant company and the company’s military force became about twice the size of the British government’s standing military force. That approach made the British East India Company extremely powerful and the British people very rich and powerful. Additionally, at the same time, around 1760, the British created a whole new way of making things and becoming rich while raising people’s living standards. It was called the Industrial Revolution. It was through machine production, particularly propelled by the steam engine. So, this relatively small country of well-educated people became the world’s most powerful country by combining inventiveness, capitalism, great ships and other technologies that allowed them to go global, and a great military to create the British empire that was dominant for the next 100 years. Naturally London replaced Amsterdam as the world’s capital markets center and continued to innovate financial products. Later in that 100-year peaceful and prosperous period, from 1870 to the early 1900s the inventive and prosperous boom continued as the Second Industrial Revolution. During it human ingenuity created enormous technological advances that raised living standards and made those who developed them and owned them rich. This period was for Great Britain what “the Dutch Golden Age” was for the Dutch about 200 years earlier because it raised the power in all the eight key ways—via excellent education, new inventions and technologies, stronger competitiveness, higher output and trade, a stronger military and financial center, and a more widely used reserve currency.At this time several other countries used this period of relative peace and prosperity to get richer and stronger by colonizing enormous swaths of the world. As is typical during this phase, other countries copied Britain’s technologies and techniques and flourished themselves, producing prosperity and, with it, great wealth gaps. For example, during this period there was the invention of steel production, the development of the automobile, and the development of electricity and its applications such as for communications including Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb and phonograph. This is when the United States grew strongly to become a leading world power. These countries became very rich and their wealth gaps increased. That period was called “the Gilded Age” in the US, “la Belle Époque” in France, and “the Victorian Era” in England. As is typical at such times the leading power, Great Britain, became more indulgent while its relative power declined, and it started to borrow excessively.As other countries became more competitive, the British empire became more costly and less profitable to maintain. Most importantly other European countries and the US got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. As shown in the chart of the standing of empires above, the US became a comparable power economically and militarily around 1900 though the UK retained stronger military power, trade, and reserve currency status, and the US continued to gain relative strength from there.From 1900 until 1914, as a consequence of the large wealth gaps, there became 1) greater arguments about how wealth should be divided within countries and 2) greater conflicts and comparabilities in economic and military powers that existed between European countries. As is typical at such times the international conflicts led to alliances being formed and eventually led to war. Before the war the conflicts and the alliances were built around money and power considerations. For example, typical of conflicting powers that seek to cut off their enemies’ access to money and credit, Germany under Bismarck refused to let Russia sell its bonds in Berlin, which led them to be sold in Paris, which reinforced the French-Russian alliance. The wealth gap in Russia led it to tumble into revolution in 1917 and out of the war, which is a whole other dramatic story about fighting over wealth and power that is examined in Part 2 of this book. Similar to the economically motivated shipping conflict between the British and the Dutch, Germany sank five merchant ships that were going to England in the first years of the war. That brought the United States into the war. Frankly, the complexities of the situations leading up to World War I are mind-boggling, widely debated among historians, and way beyond me. That war, which was really the first world war because it involved countries all around the world because the world had become global, lasted from 1914 until 1918 and cost the lives of an estimated 8.5 million soldiers and 13 million civilians. As it ended, the Spanish flu arrived, killing an estimated 20-50 million people over two years. So 1914-20 was a terrible time. The Rise of the American Empire and the US Dollar After World War I[3]As is typical after wars, the winning powers—in this case the US, Britain, France, Japan, and Italy—met to set out the new world order. That meeting, called the Paris Peace Conference, took place in early 1919, lasted for six months, and concluded with the Treaty of Versailles. In that treaty the territories of the losing powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman empire, and Bulgaria) were carved up and put under the controls of the winning empires and the losing powers were put deeply into debt to the winning powers to pay back the winning countries’ war costs with these debts payable in gold. The United States was then clearly recognized as a leading power so it played a role in shaping the new world order. In fact the term “new world order” came about in reference to US President Woodrow Wilson’s vision for how countries would operate in pursuit of their collective interest through a global governance system (the League of Nations) which was a vision that quickly failed. After World War I the US chose to remain more isolationist while Britain continued to expand and oversee its global colonial empire. The monetary system in the immediate post-war period was in flux. While most countries endeavored to restore gold convertibility, currency stability against gold only came after a period of sharp devaluations and inflation.The large foreign debt burdens placed on Germany set the stage for 1) Germany’s post-war inflationary depression from 1920 to 1923 that wiped out the debts and was followed by Germany’s strong economic and military recovery, and 2) a decade of peace and prosperity elsewhere, which became the “Roaring ’20s.” During that time the United States also followed a classic capitalist approach to resource allocation and New York became a rival financial center to London, channeling debt and investments into various businesses. Other countries became more competitive and prosperous and increasingly challenged the leading powers. Most importantly Germany, Japan, and the US got stronger economically and militarily in the classic ways laid out in Chapter 1. However, the US was isolationist and didn’t have a big colonial empire past its borders so it was essentially out of the emerging conflict. As shown in the chart of the standing of empires above, Germany and Japan both gained in power relative to the UK during this interwar period, though the UK remained stronger. As is typical, the debts and the wealth gaps that were built up in the 1920s led to the debt bubbles that burst in 1929 which led to depressions, which led to the printing of money, which led to devaluations of currencies and greater internal and external conflicts over wealth and power in the 1930s. For example, in the United States and the UK, while there were redistributions of wealth and political power, capitalism and democracy were maintained, while in Germany, Japan, Italy, and Spain they were not maintained. Russia played a significant peripheral role in ways I won’t delve into. China at the time was weak, fragmented, and increasingly controlled by a rising and increasingly militaristic and nationalistic Japan. To make a long story short, the Japanese and Germans started to make territorial expansions in the early to mid-1930s, which led to wars in Europe and Asia in the late 1930s that ended in 1945. As is typical, before all-out wars were declared there was about a decade of economic, technological, geopolitical, and capital wars when the conflicting powers approached comparability and tested and tried to intimidate the other powers. While 1939 and 1941 are known as the official start of the wars in Europe and the Pacific, the wars really started about 10 years before that, as economic conflicts that were at first limited progressively grew into World War II. As Germany and Japan became more expansionist economic and military powers, they increasingly competed with the UK, US, and France for both resources and influence over territories. That brought about the second world war which, as usual, was won by the winning countries coming up with new technologies (the nuclear bomb, while the most important, was just one of the newly invented weapons). Over 20 million died directly in the military conflicts, and the total death count was still higher. So 1930-45, which was a period of depression and war, was a terrible time. The Rise of the American Empire and the US Dollar After World War IIAs is typical after wars, the winning powers—most importantly the US, Britain, and Russia—met to set out the new world order. While the Bretton Woods Conference, Yalta Conference, and Potsdam Conference were the most noteworthy, several other meetings occurred that shaped the new world order, which included carving up the world and redefining countries and areas of influence and establishing a new money and credit system. In this case, the world was divided into the US-controlled capitalist/democratic countries and Russia-controlled communist and autocratically controlled countries, each with their own monetary systems. Germany was split into pieces, with the United States, Great Britain, and France having control of the West and Russia having control of the East. Japan was under US control and China returned to a state of civil war, mostly about how to divide the wealth, which was between communists and capitalists (i.e., the Nationalists). Unlike after World War I when the United States chose to be relatively isolationist, after World War II the United States took the primary leadership role as it had most of the economic, geopolitical, and military responsibility. The US followed a capitalist system. The new monetary system of the US-led countries had the dollar linked to gold and had most other countries’ currencies tied to the dollar. This system was followed by over 40 countries. Because the US had around two-thirds of the world’s gold then and because the US was much more powerful economically and militarily than any other country, this monetary system has worked best and carried on until now. As for the other countries that were not part of this system—most importantly Russia and those countries that were brought into the Soviet Union and the satellite countries that the Soviets controlled—they were built on a much weaker foundation that eventually broke down. Unlike after World War I, when the losing countries were burdened with large debts, countries that were under US control, including the defeated countries, received massive financial aid from the US via the Marshall Plan. At the same time the currencies and debts of the losing countries were wiped out, with those holding them losing all of their wealth in them. Great Britain was left heavily indebted from its war borrowings and faced the gradual end of the colonial era which would lead to the unraveling of its empire which was becoming uneconomic to have.During this post-World War II period the United States, its allies, and the countries that were under its influence followed a classic capitalist-democratic approach to resource allocation. New York flourished as the world’s pre-eminent financial center, and a new big debt and capital markets cycle began. That produced what has thus far been a relatively peaceful and prosperous 75-year period that has brought us to today.As is typical of this peaceful and prosperous part of the cycle, in the 1950-70 period there was productive debt growth and equity market development that were essential for financing innovation and development early on. That eventually led to too much debt being required to finance both war and domestic needs—what was called “guns and butter.” The Vietnam War and the “War on Poverty” occurred in the US. Other countries also became overly indebted and the British indebtedness became over-leveraged which led to a number of currency devaluations, most importantly the breakdown of the Bretton Woods monetary system (though countries like the UK and Italy had already devalued prior to that time). Then in 1971, when it was apparent that the US didn’t have enough gold in the bank to meet the claims on gold that it had put out, the US defaulted on its promise to deliver gold for paper dollars which ended the Type 2 gold-backed monetary system, and the world moved to a fiat monetary system. As is typical, this fiat monetary system initially led to a wave of great dollar money and debt creation that led to a big wave of inflation that carried until 1980-82 and led to the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. It was followed by three other waves of debt-financed speculations, bubbles, and busts—1) the 1982 and 2000 money and credit expansion that produced a dot-com bubble that led to the 2000-01 recession, 2) the 2002-07 money and credit expansion that produced a real estate bubble that led to the 2008 Great Recession, and 3) the 2009-19 money and credit expansion that produced the investment bubble that preceded the COVID-19 downturn. Each of these cycles raised debt and non-debt obligations (e.g., for pensions and healthcare) to progressively higher levels and led the reserve currency central banks of the post-war allies to push interest rates to unprecedented low levels and to print unprecedented amounts of money. Also classically, the wealth, values, and political gaps widened within countries, which increases internal conflicts during economic downturns. That is where we now are. During this prosperous post-war period many countries became more competitive with the leading powers economically and militarily. The Soviet Union/Russia initially followed a communist resource allocation approach as did China and a number of other smaller countries. None of these countries became competitive following this approach. However, the Soviet Union did develop nuclear weapons to become militarily threatening and gradually a number of other countries followed in developing nuclear weapons. These weapons were never used because using them would produce mutually assured destruction. Because of its economic failures the Soviet Union/Russia could not afford to support a) its empire, b) its economy, and c) its military at the same time in the face of US President Ronald Reagan’s arms race spending. As a result the Soviet Union broke down in 1991 and abandoned communism. The breakdown of its money/credit/economic system was disastrous for it economically and geopolitically for most of the 1990s. In the 1980-95 period most communist countries abandoned classic communism and the world entered a very prosperous period of globalization and free-market capitalism. In China, Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 led Deng Xiaoping to a shift in economic policies to include capitalist elements including private ownership of large businesses, the development of debt and equities markets, great technological and commercial innovations, and even the flourishing of billionaire capitalists—all, however, under the strict control of the Communist Party. As a result of this shift and the simultaneous shift in the world to greater amounts of globalism China grew much stronger in most ways. For example, since I started visiting China in 1984, the education of its population has improved dramatically, the real per capita income has multiplied by 24, and it has become the largest country in the world in trade (exceeding the US share of world trade), a rival technology leader, the holder of the greatest foreign reserves assets in the world by a factor of over two, the largest lender/investor in the emerging world, the second most powerful military power, and a geopolitical rival of the United States. And it is growing in power at a significantly faster pace than the United States and other “developed countries.” At the same time, we are in a period of great inventiveness due to advanced information/data management and artificial intelligence supplementing human intelligence with the Americans and Chinese leading the way. As shown at the outset of Chapter 1, human adaptability and inventiveness has proven to be the greatest force in solving problems and creating advances. Also, because the world is richer and more skilled than ever before, there is a tremendous capacity to make the world better for more people than ever if people can work together to make the whole pie as big as possible and to divide it well. That brings us to where we now are. As you can see, all three of these rises and declines followed the classic script laid out in Chapter 1 and summarized in the charts at the beginning of this chapter, though each had its own particular turns and twists. Now let’s look at these cases, especially the declines, more closely.A Closer Look at the Rises and Declines of the Leading Empires Over the Last 500 YearsThe Dutch Empire and the Dutch GuilderBefore we get to the collapse of the Dutch empire and the Dutch guilder let’s take a quick look at the whole arc of its rise and decline. While I previously showed you the aggregated power index for the Dutch empire, the chart below shows the eight powers that make it up from the ascent around 1575 to the decline around 1780. In it, you can see the story behind the rise and decline.  After declaring independence in 1581, the Dutch fought off the Spanish and built a global trading empire that became responsible for over a third of global trade largely via the first mega-corporation, the Dutch East India Company. As shown in the chart above, with a strong educational background the Dutch innovated in a number of areas. They produced roughly 25% of global inventions in the early 17th century,[4] most importantly in shipbuilding, which led to a great improvement in Dutch competitiveness and its share of world trade. Propelled by these ships and the capitalism that provided the money to fuel these expeditions, the Dutch became the largest traders in the world, accounting for about one-third of world trade.[5] As the ships traveled around the world, the Dutch built a strong military to defend them and their trade routes. As a result of this success they got rich. Income per capita rose to over twice that of most other major European powers.[6]They invested more in education. Literacy rates became double the world average. They created an empire spanning from the New World to Asia, and they formed the first major stock exchange with Amsterdam becoming the world’s most important financial center. The Dutch guilder became the first global reserve currency, accounting for over a third of all international transactions.[7] For these reasons over the course of the late 1500s and 1600s, the Dutch became a global economic and cultural power. They did all of this with a population of only 1-2 million people. Below is a brief summary of the wars they had to fight to build and hold onto their empire. As shown, they were all about money and power.Eighty Years’ War (1566-1648): This was a revolt by the Netherlands against Spain (one of the strongest empires of that era), which eventually led to Dutch independence. The Protestant Dutch wanted to free themselves from the Catholic rule of Spain and eventually managed to become de facto independent. Between 1609 and 1621, the two nations had a ceasefire. Eventually, the Dutch were recognized by Spain as independent in the Peace of Munster, which was signed together with the Treaty of Westphalia, ending both the Eighty Years’ War as well as the Thirty Years’ War.[8] First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654): This was a trade war. More specifically, in order to protect its economic position in North America and damage the Dutch trade that the English were competing with, the English Parliament passed the first of the Navigation Acts in 1651 that mandated that all goods from its American colonies must be carried by English ships, which set off hostilities between the two countries.[9]The Dutch-Swedish War (1657–1660): This war centered around the Dutch wanting to maintain low tolls on the highly profitable Baltic trade routes. This was threatened when Sweden declared war on Denmark, a Dutch ally. The Dutch defeated the Swedes and maintained the favorable trade arrangement.[10]The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667): England and the Netherlands fought again over another trade dispute, which again ended with a Dutch victory.[11]The Franco-Dutch War (1672-1678) and the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674): This was also a fight over trade. It was between France and England on one side and the Dutch (called the United Provinces), the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain on the other.[12] The Dutch largely stopped French plans to conquer the Netherlands and forced France to reduce some of its tariffs against Dutch trade,[13] but the war was more expensive than previous conflicts, which increased their debts and hurt the Dutch financially.The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784): This was fought between the Dutch and the rapidly strengthening British, partially in retaliation for Dutch support of the US in the American Revolution. The war ended in significant defeat for the Dutch, and the costs of the fighting and eventual peace helped usher in the end of the guilder as a reserve currency.[14]The chart below shows the Dutch power index with the key war periods noted. After declaring independence in 1581, the Dutch fought off the Spanish and built a global trading empire that became responsible for over a third of global trade largely via the first mega-corporation, the Dutch East India Company. As shown in the chart above, with a strong educational background the Dutch innovated in a number of areas. They produced roughly 25% of global inventions in the early 17th century,[4] most importantly in shipbuilding, which led to a great improvement in Dutch competitiveness and its share of world trade. Propelled by these ships and the capitalism that provided the money to fuel these expeditions, the Dutch became the largest traders in the world, accounting for about one-third of world trade.[5] As the ships traveled around the world, the Dutch built a strong military to defend them and their trade routes. As a result of this success they got rich. Income per capita rose to over twice that of most other major European powers.[6]They invested more in education. Literacy rates became double the world average. They created an empire spanning from the New World to Asia, and they formed the first major stock exchange with Amsterdam becoming the world’s most important financial center. The Dutch guilder became the first global reserve currency, accounting for over a third of all international transactions.[7] For these reasons over the course of the late 1500s and 1600s, the Dutch became a global economic and cultural power. They did all of this with a population of only 1-2 million people. Below is a brief summary of the wars they had to fight to build and hold onto their empire. As shown, they were all about money and power.Eighty Years’ War (1566-1648): This was a revolt by the Netherlands against Spain (one of the strongest empires of that era), which eventually led to Dutch independence. The Protestant Dutch wanted to free themselves from the Catholic rule of Spain and eventually managed to become de facto independent. Between 1609 and 1621, the two nations had a ceasefire. Eventually, the Dutch were recognized by Spain as independent in the Peace of Munster, which was signed together with the Treaty of Westphalia, ending both the Eighty Years’ War as well as the Thirty Years’ War.[8] First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654): This was a trade war. More specifically, in order to protect its economic position in North America and damage the Dutch trade that the English were competing with, the English Parliament passed the first of the Navigation Acts in 1651 that mandated that all goods from its American colonies must be carried by English ships, which set off hostilities between the two countries.[9]The Dutch-Swedish War (1657–1660): This war centered around the Dutch wanting to maintain low tolls on the highly profitable Baltic trade routes. This was threatened when Sweden declared war on Denmark, a Dutch ally. The Dutch defeated the Swedes and maintained the favorable trade arrangement.[10]The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667): England and the Netherlands fought again over another trade dispute, which again ended with a Dutch victory.[11]The Franco-Dutch War (1672-1678) and the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674): This was also a fight over trade. It was between France and England on one side and the Dutch (called the United Provinces), the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain on the other.[12] The Dutch largely stopped French plans to conquer the Netherlands and forced France to reduce some of its tariffs against Dutch trade,[13] but the war was more expensive than previous conflicts, which increased their debts and hurt the Dutch financially.The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784): This was fought between the Dutch and the rapidly strengthening British, partially in retaliation for Dutch support of the US in the American Revolution. The war ended in significant defeat for the Dutch, and the costs of the fighting and eventual peace helped usher in the end of the guilder as a reserve currency.[14]The chart below shows the Dutch power index with the key war periods noted.  As shown, the seeds of Dutch decline were sown in the latter part of the 17th century as they started to lose their competitiveness and became overextended globally trying to support an empire that had become more costly than profitable. Increased debt-service payments squeezed them while their worsening competitiveness hurt their income from trade. Earnings from business abroad also fell. Wealthy Dutch savers moved their cash abroad both to get out of Dutch investments and into British investments, which were more attractive due to strong earnings growth and higher yields.[15] While debt burdens had grown through most of the 1700s,[16]the Dutch guilder remained widely accepted around the world as a reserve currency so it held up solely because of the functionality of and faith in it.[17] (As explained earlier, reserve currency status classically lags the decline of other key drivers of the rise and fall of empires.) As shown by the black line in the first chart above (designating the extent the currency is used as a reserve currency) the guilder remained widely used as a global reserve currency after the Dutch empire started to decline, up until the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, which began in 1780 and ended in 1784.[18]The simmering conflict between the rising British and the declining Dutch had escalated after the Dutch traded arms with the colonies during the American Revolution.[19] In retaliation the English delivered a massive blow to the Dutch in the Caribbean and ended up controlling Dutch territory in the East and West Indies.[20] The war required heavy expenditure by the Dutch to rebuild their dilapidated navy: the Dutch East India Company lost half its ships[21] and access to its key trade routes while heavily borrowing from the Bank of Amsterdam to stay alive. And the war forced the Dutch to accumulate large debts beyond these.[22] The main reason the Dutch lost the war was that they let their navy become much weaker than Britain’s because of disinvestment into military capacity in order to spend on domestic indulgences.[23] In other words, they tried to finance both guns and butter with their reserve currency, didn’t have enough buying power to support the guns despite their great ability to borrow due to their having the leading reserve currency, and became financially and militarily defeated by the British who were stronger in both respects.Most importantly, this war destroyed the profitability and balance sheet of the Dutch East India Company.[24] While it was already in decline due to its reduced competitiveness, it ran into a liquidity crisis after a collapse in trade caused by British blockades on the Dutch coast and in the Dutch East Indies.[25] As shown below, it suffered heavy losses during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War and began borrowing aggressively from the Bank of Amsterdam because it was too systemically important for the Dutch government. As shown, the seeds of Dutch decline were sown in the latter part of the 17th century as they started to lose their competitiveness and became overextended globally trying to support an empire that had become more costly than profitable. Increased debt-service payments squeezed them while their worsening competitiveness hurt their income from trade. Earnings from business abroad also fell. Wealthy Dutch savers moved their cash abroad both to get out of Dutch investments and into British investments, which were more attractive due to strong earnings growth and higher yields.[15] While debt burdens had grown through most of the 1700s,[16]the Dutch guilder remained widely accepted around the world as a reserve currency so it held up solely because of the functionality of and faith in it.[17] (As explained earlier, reserve currency status classically lags the decline of other key drivers of the rise and fall of empires.) As shown by the black line in the first chart above (designating the extent the currency is used as a reserve currency) the guilder remained widely used as a global reserve currency after the Dutch empire started to decline, up until the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, which began in 1780 and ended in 1784.[18]The simmering conflict between the rising British and the declining Dutch had escalated after the Dutch traded arms with the colonies during the American Revolution.[19] In retaliation the English delivered a massive blow to the Dutch in the Caribbean and ended up controlling Dutch territory in the East and West Indies.[20] The war required heavy expenditure by the Dutch to rebuild their dilapidated navy: the Dutch East India Company lost half its ships[21] and access to its key trade routes while heavily borrowing from the Bank of Amsterdam to stay alive. And the war forced the Dutch to accumulate large debts beyond these.[22] The main reason the Dutch lost the war was that they let their navy become much weaker than Britain’s because of disinvestment into military capacity in order to spend on domestic indulgences.[23] In other words, they tried to finance both guns and butter with their reserve currency, didn’t have enough buying power to support the guns despite their great ability to borrow due to their having the leading reserve currency, and became financially and militarily defeated by the British who were stronger in both respects.Most importantly, this war destroyed the profitability and balance sheet of the Dutch East India Company.[24] While it was already in decline due to its reduced competitiveness, it ran into a liquidity crisis after a collapse in trade caused by British blockades on the Dutch coast and in the Dutch East Indies.[25] As shown below, it suffered heavy losses during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War and began borrowing aggressively from the Bank of Amsterdam because it was too systemically important for the Dutch government.  [26]As shown in the chart below the Dutch East India Company, which was essentially the Dutch economy and military wrapped into a company, started to make losses in 1780, which became enormous during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. [26]As shown in the chart below the Dutch East India Company, which was essentially the Dutch economy and military wrapped into a company, started to make losses in 1780, which became enormous during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.  As deposit holders at the Bank of Amsterdam realized the bank was “lending” freshly printed guilders to save the Dutch East India Company, there was a run on the Bank of Amsterdam.[27] As investors pulled back and borrowing needs increased, gold was preferred to paper money, those with paper money exchanged it for gold at the Bank of Amsterdam, and it became clear that there wouldn’t be enough gold. The run on the bank and the run on the guilder accelerated throughout the war, as it became increasingly apparent that the Dutch would lose and depositors could anticipate that the bank would print more money and have to devalue the guilder.[28] Guilders were backed by precious metals, but as the supply of guilders rose and investors could see what was happening they turned their guilders in for gold and silver so the ratio of claims on gold and silver rose, which caused more of the same until the Bank of Amsterdam was wiped out of its precious metal holdings. The supply of guilders continued to soar while demand for them fell. As deposit holders at the Bank of Amsterdam realized the bank was “lending” freshly printed guilders to save the Dutch East India Company, there was a run on the Bank of Amsterdam.[27] As investors pulled back and borrowing needs increased, gold was preferred to paper money, those with paper money exchanged it for gold at the Bank of Amsterdam, and it became clear that there wouldn’t be enough gold. The run on the bank and the run on the guilder accelerated throughout the war, as it became increasingly apparent that the Dutch would lose and depositors could anticipate that the bank would print more money and have to devalue the guilder.[28] Guilders were backed by precious metals, but as the supply of guilders rose and investors could see what was happening they turned their guilders in for gold and silver so the ratio of claims on gold and silver rose, which caused more of the same until the Bank of Amsterdam was wiped out of its precious metal holdings. The supply of guilders continued to soar while demand for them fell.  The Bank of Amsterdam had no choice since the company was too important to allow to fail both because of its significance to the economy and its outstanding debt in the Dutch financial system, so the Bank of Amsterdam began “lending” large sums of newly printed guilders to the company. During the war, policy makers also used the bank to lend to the government.[29] The chart below shows this explosion of loans on the bank’s balance sheet through the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (note: there was about 20 million bank guilder outstanding at the start of the war).[30] The Bank of Amsterdam had no choice since the company was too important to allow to fail both because of its significance to the economy and its outstanding debt in the Dutch financial system, so the Bank of Amsterdam began “lending” large sums of newly printed guilders to the company. During the war, policy makers also used the bank to lend to the government.[29] The chart below shows this explosion of loans on the bank’s balance sheet through the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (note: there was about 20 million bank guilder outstanding at the start of the war).[30] [31]Interest rates rose and the Bank of Amsterdam had to devalue, undermining the credibility of the guilder as a storehold of value.[32] Over the years, and at this moment of crisis, the bank had created many more “paper money” claims on the hard money in the bank than could be met so that led to a classic run on the Bank of Amsterdam, which led to the collapse of the Dutch guilder.[33] It also led to the British pound clearly replacing the Dutch guilder as the leading reserve currency. What happened to the Dutch was classic as described in both Chapter 1’s very brief summary of why empires rise and fall and in Chapter 2’s description of how money, credit, and debt work. As for the money, credit, and debt cycle, the Bank of Amsterdam started with a Type 1 monetary system that morphed into a Type 2 monetary system. It started with just coins that led to the bank having a 1:1 backing of paper money by metal, so the bank provided a more convenient form of hard money. The claims on money were then allowed to rise relative to the hard money to increasingly become a Type 2 monetary system, in which paper money seems to acquire a value itself as well as a claim on hard money (coins), though the money wasn’t fully backed. This transition usually happens at times of financial stress and military conflict. And it is risky because the transition decreases trust in the currency and adds to the risk of a bank-run-like dynamic. While we won’t go deeply into the specifics of the war, the steps taken by policy makers during the period led to the loss of Dutch financial power so are worth describing because they are so archetypical when there is a clear shift in power and the losing country has a bad income statement and balance sheet. This period was like that and ended with the guilder supplanted by the pound as the world’s reserve currency and London succeeding Amsterdam as the world’s financial center. Deposits (i.e., holdings of short-term debt) of the Bank of Amsterdam, which had been a reliable storehold of wealth for nearly two centuries, began to trade at large discounts to guilder coins (which were made of gold and silver).[34] The bank used its holdings of other countries’ debt (i.e., its currency reserves) to buy its currency on the open market to support the value of deposits, but it lacked adequate foreign currency reserves to support the guilder.[35] Accounts backed by coin held at the bank plummeted from 17 million guilder in March 1780 to only 300,000 in January 1783 as owners of these gold and silver coins wanted to get them rather than continue to hold the promises of the Bank of Amsterdam to deliver them.[36]The running out of money by the Bank of Amsterdam marked the end of the Dutch empire and the guilder as a reserve currency. In 1791 the bank was taken over by the City of Amsterdam,[37] and in 1795 the French revolutionary government overthrew the Dutch Republic, establishing a client state in its place.[38] After being nationalized in 1796, rendering its stock worthless, the Dutch East India Company’s charter expired in 1799.[39]The following charts show the exchange rates between the guilder and the pound/gold; as it became clear that the bank no longer had any credibility and that the currency was no longer a good storehold of wealth, investors fled to other assets and currency.[40] [31]Interest rates rose and the Bank of Amsterdam had to devalue, undermining the credibility of the guilder as a storehold of value.[32] Over the years, and at this moment of crisis, the bank had created many more “paper money” claims on the hard money in the bank than could be met so that led to a classic run on the Bank of Amsterdam, which led to the collapse of the Dutch guilder.[33] It also led to the British pound clearly replacing the Dutch guilder as the leading reserve currency. What happened to the Dutch was classic as described in both Chapter 1’s very brief summary of why empires rise and fall and in Chapter 2’s description of how money, credit, and debt work. As for the money, credit, and debt cycle, the Bank of Amsterdam started with a Type 1 monetary system that morphed into a Type 2 monetary system. It started with just coins that led to the bank having a 1:1 backing of paper money by metal, so the bank provided a more convenient form of hard money. The claims on money were then allowed to rise relative to the hard money to increasingly become a Type 2 monetary system, in which paper money seems to acquire a value itself as well as a claim on hard money (coins), though the money wasn’t fully backed. This transition usually happens at times of financial stress and military conflict. And it is risky because the transition decreases trust in the currency and adds to the risk of a bank-run-like dynamic. While we won’t go deeply into the specifics of the war, the steps taken by policy makers during the period led to the loss of Dutch financial power so are worth describing because they are so archetypical when there is a clear shift in power and the losing country has a bad income statement and balance sheet. This period was like that and ended with the guilder supplanted by the pound as the world’s reserve currency and London succeeding Amsterdam as the world’s financial center. Deposits (i.e., holdings of short-term debt) of the Bank of Amsterdam, which had been a reliable storehold of wealth for nearly two centuries, began to trade at large discounts to guilder coins (which were made of gold and silver).[34] The bank used its holdings of other countries’ debt (i.e., its currency reserves) to buy its currency on the open market to support the value of deposits, but it lacked adequate foreign currency reserves to support the guilder.[35] Accounts backed by coin held at the bank plummeted from 17 million guilder in March 1780 to only 300,000 in January 1783 as owners of these gold and silver coins wanted to get them rather than continue to hold the promises of the Bank of Amsterdam to deliver them.[36]The running out of money by the Bank of Amsterdam marked the end of the Dutch empire and the guilder as a reserve currency. In 1791 the bank was taken over by the City of Amsterdam,[37] and in 1795 the French revolutionary government overthrew the Dutch Republic, establishing a client state in its place.[38] After being nationalized in 1796, rendering its stock worthless, the Dutch East India Company’s charter expired in 1799.[39]The following charts show the exchange rates between the guilder and the pound/gold; as it became clear that the bank no longer had any credibility and that the currency was no longer a good storehold of wealth, investors fled to other assets and currency.[40] [41]The chart below shows the returns of holding the Dutch East India Company for investors starting in various years. As with most bubble companies, it originally did great, with great fundamentals, which attracted more investors even as its fundamentals started to weaken, but it increasingly got into debt, until the failed fundamentals and excessive debt burdens broke the company. [41]The chart below shows the returns of holding the Dutch East India Company for investors starting in various years. As with most bubble companies, it originally did great, with great fundamentals, which attracted more investors even as its fundamentals started to weaken, but it increasingly got into debt, until the failed fundamentals and excessive debt burdens broke the company.  As is typical, with the decline in power of the leading empire and the rise in power of the new empire, the returns of investment assets in the declining empire fell relative to the returns of investing in the rising empire. For example, as shown below, the returns on investments in the British East India Company far exceeded those in the Dutch East India Company, and the returns of investing in Dutch government bonds were terrible relative to the returns of investing in English government bonds. This was reflective of virtually all investments in these two countries. As is typical, with the decline in power of the leading empire and the rise in power of the new empire, the returns of investment assets in the declining empire fell relative to the returns of investing in the rising empire. For example, as shown below, the returns on investments in the British East India Company far exceeded those in the Dutch East India Company, and the returns of investing in Dutch government bonds were terrible relative to the returns of investing in English government bonds. This was reflective of virtually all investments in these two countries.  [42]The British Empire and the British PoundBefore we get to the collapse of the British empire and the British pound, let’s take a quick look at the whole arc of its rise and decline. While I previously showed you the aggregated power index for the British empire, the chart below shows the eight powers that make it up. It shows these from the ascent around 1700 to the decline in the early 1900s. In it, you can see the story behind the rise and decline. [42]The British Empire and the British PoundBefore we get to the collapse of the British empire and the British pound, let’s take a quick look at the whole arc of its rise and decline. While I previously showed you the aggregated power index for the British empire, the chart below shows the eight powers that make it up. It shows these from the ascent around 1700 to the decline in the early 1900s. In it, you can see the story behind the rise and decline.  The British empire’s rise began before 1600, with steadily strengthening competitiveness, education, and innovation/technology—the classic leading factors for a power’s rise. As shown and previously described, in the late 1700s the British military power became pre-eminent and it beat its leading economic competitor and the leading reserve currency empire of its day in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. It also successfully fought other European rivals like France in a number of conflicts that culminated in the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s. Then it became extremely rich by being the dominant economic power. At its peak in the 19th century, the UK’s 2.5% of the world’s population produced 20% of the world’s income, and the UK controlled over 40% of global exports. This economic strength grew in tandem with a strong military, which, along with the privately driven conquests of the British East India Company, drove the creation of a global empire upon which “the sun never set,” controlling over 20% of the world’s land mass and 25% of the global population prior to the outbreak of World War I. With a lag, as is classic, its capital—London—emerged as the global financial center and its currency—the pound—emerged as the leading global reserve currency. As is typical its reserve status remained well after other measures of power started declining in the late 19th century and as powerful rivals like the US and Germany rose. As shown in the chart above, almost all of the British empire’s relative powers began to slip as competitors emerged around 1900. At the same time wealth gaps were large and internal conflicts over wealth were emerging. As you know, despite winning both World War I and World War II the British were left with large debts, a huge empire that was more costly than profitable, numerous rivals that were more competitive, and a population that had big wealth gaps which led to big political gaps. As I previously summarized what happened in the 1914 to post-World War II period, I will skip ahead to the end of World War II in 1945 and the start of the new world order that we are now in. I will be focusing on how the pound lost its reserve currency status. Although the US had overtaken the UK militarily, economically, politically, and financially long before the end of World War II, it took more than 20 years after the war for the British pound to fully lose its status as an international reserve currency. Just like the world’s most widely spoken language becomes so deeply woven into the fabric of international dealings that it is difficult to replace, the same is true of the world’s most widely used reserve currency. In the case of the British pound, other countries’ central banks continued to hold a sizable share of their reserves in pounds through the 1950s, and about half of all international trade was denominated in sterling in 1960. Still, the pound began to lose its status right at the end of the war because smart folks could see the UK’s increased debt load, its low net reserves, and the great contrast with the United States’ financial condition (which emerged from the war as the world’s pre-eminent creditor and with a very strong balance sheet). The decline in the British pound was a chronic affair that happened through several significant devaluations over many years. After efforts at making the pound convertible failed in 1946-47, the pound devalued by 30% against the dollar in 1949. Though this worked in the short term, over the next two decades the declining competitiveness of the British led to repeated balance of payments strains that culminated with central banks actively selling sterling reserves to accumulate dollar reserves following the devaluation of 1967. Around this time the deutschmark began to re-emerge and took the pound’s place as the second-most widely held reserve currency. The charts below paint the picture. The British empire’s rise began before 1600, with steadily strengthening competitiveness, education, and innovation/technology—the classic leading factors for a power’s rise. As shown and previously described, in the late 1700s the British military power became pre-eminent and it beat its leading economic competitor and the leading reserve currency empire of its day in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. It also successfully fought other European rivals like France in a number of conflicts that culminated in the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s. Then it became extremely rich by being the dominant economic power. At its peak in the 19th century, the UK’s 2.5% of the world’s population produced 20% of the world’s income, and the UK controlled over 40% of global exports. This economic strength grew in tandem with a strong military, which, along with the privately driven conquests of the British East India Company, drove the creation of a global empire upon which “the sun never set,” controlling over 20% of the world’s land mass and 25% of the global population prior to the outbreak of World War I. With a lag, as is classic, its capital—London—emerged as the global financial center and its currency—the pound—emerged as the leading global reserve currency. As is typical its reserve status remained well after other measures of power started declining in the late 19th century and as powerful rivals like the US and Germany rose. As shown in the chart above, almost all of the British empire’s relative powers began to slip as competitors emerged around 1900. At the same time wealth gaps were large and internal conflicts over wealth were emerging. As you know, despite winning both World War I and World War II the British were left with large debts, a huge empire that was more costly than profitable, numerous rivals that were more competitive, and a population that had big wealth gaps which led to big political gaps. As I previously summarized what happened in the 1914 to post-World War II period, I will skip ahead to the end of World War II in 1945 and the start of the new world order that we are now in. I will be focusing on how the pound lost its reserve currency status. Although the US had overtaken the UK militarily, economically, politically, and financially long before the end of World War II, it took more than 20 years after the war for the British pound to fully lose its status as an international reserve currency. Just like the world’s most widely spoken language becomes so deeply woven into the fabric of international dealings that it is difficult to replace, the same is true of the world’s most widely used reserve currency. In the case of the British pound, other countries’ central banks continued to hold a sizable share of their reserves in pounds through the 1950s, and about half of all international trade was denominated in sterling in 1960. Still, the pound began to lose its status right at the end of the war because smart folks could see the UK’s increased debt load, its low net reserves, and the great contrast with the United States’ financial condition (which emerged from the war as the world’s pre-eminent creditor and with a very strong balance sheet). The decline in the British pound was a chronic affair that happened through several significant devaluations over many years. After efforts at making the pound convertible failed in 1946-47, the pound devalued by 30% against the dollar in 1949. Though this worked in the short term, over the next two decades the declining competitiveness of the British led to repeated balance of payments strains that culminated with central banks actively selling sterling reserves to accumulate dollar reserves following the devaluation of 1967. Around this time the deutschmark began to re-emerge and took the pound’s place as the second-most widely held reserve currency. The charts below paint the picture.  On the following pages we will cover in greater detail the specific stages of this decline, firstly with the convertibility crisis of 1947 and the 1949 devaluation, secondly with the gradual evolution of the pound’s status relative to the dollar through the 1950s and early 1960s, and thirdly with the balance of payments crisis of 1967 and subsequent devaluation. We will focus in on the currency crises. 1) The Pound’s Suspended Convertibility in 1946 and Its Devaluation in 1949The 1940s are frequently referred to as “crisis years”[43] for sterling. The war required the UK to borrow immensely from its allies and colonies,[44]and those obligations were required to be held in sterling. These war debts financed about a third of the war effort. When the war ended, the UK could not meet its debt obligations without the great pain of raising taxes or cutting government spending, so it necessarily mandated that its debt assets (i.e., its bonds) could not be proactively sold by its former colonies. As such, the UK emerged from World War II with strict controls on foreign exchange. The Bank of England’s approval was required to convert pounds into dollars, whether to buy US goods or purchase US financial assets (i.e., current and capital account convertibility was suspended). To ensure the pound would function as an international reserve currency in the post-war era, and to prepare the global economy for a transition to the Bretton Woods monetary system, convertibility would have to be restored. However, because the US dollar was now the international currency of choice, the global economy was experiencing a severe shortage of dollars at the time. Virtually all Sterling Area countries (the UK and the Commonwealth countries) relied on inflows from selling goods and services and from attracting investments in dollars to get the dollars they needed while they were forced to hold their sterling-denominated bonds. The UK experienced acute balance of payments problems due to its poor external competitiveness, a domestic fuel crisis, and large war debts undermining faith in the pound as a storehold of wealth. As a result, the first effort to restore convertibility in 1947 failed completely, and it was soon followed by a large devaluation (of 30%) in 1949, to restore some competitiveness.[45]Coming into the period, there were concerns that too quick a return to convertibility would result in a run on the pound, as savers and traders shifted to holding and transacting in dollars all at once. However, the US was anxious for the UK to restore convertibility as soon as possible as restrictions on convertibility were reducing US export profits and reducing liquidity in the global economy.[46] The Bank of England was also eager to remove capital controls in order to restore the pound’s role as a global trading currency, increase financial sector revenues in London, and encourage international investors to continue saving in sterling [47] (a number of governments of European creditors, including Sweden, Switzerland, and Belgium, were having increasing conflicts with the UK over the lack of convertibility).[48] An agreement was reached after the war, under which the UK would reintroduce convertibility swiftly, and the US would provide the UK with a loan of $3.75 billion [49] (about 10% of UK GDP). While the loan offered some buffer against a potential run on the pound, it did not change the underlying imbalances in the global economy. When partial convertibility was introduced in July 1947, the pound came under considerable selling pressure. As the UK and US governments were against devaluation (as memories of the competitive devaluations in the 1930s were fresh on everyone’s minds), [50] the UK and other Sterling Area countries turned to austerity and reserve sales to maintain the peg to the dollar. Restrictions were imposed on the import of “luxury goods” from the US, defense expenditure was slashed, dollar and gold reserves were drawn down, and agreements were made between sterling economies not to diversify their reserve holdings to the dollar.[51] Prime Minister Clement Attlee gave a dramatic speech on August 6, 1947, calling for the spirit of wartime sacrifices to be made once again in order to defend the pound: “In 1940 we were delivered from mortal peril by the courage, skill, and self-sacrifice of a few. Today we are engaged in another battle for Britain. This battle cannot be won by the few. It demands a united effort by the whole nation. I am confident that this united effort will be forthcoming and that we shall again conquer.”[52]Immediately following the speech, the run on the pound accelerated. Over the next five days, the UK had to spend down $175 million of reserves to defend the peg.[53] By the end of August, convertibility was suspended, much to the anger of the US and other international investors who had bought up sterling assets in the lead-up to convertibility hoping that they would soon be able to convert those holdings to dollars. The governor of the National Bank of Belgium even threatened to stop transacting in sterling, requiring a diplomatic intervention.[54]The devaluation came two years later, as policy makers in both the UK and the US realized that the pound couldn’t return to convertibility at the current rate. UK exports were not competitive enough in global markets to earn the foreign exchange needed to support the pound, reserves were dwindling, and the US was unwilling to continue shoring up the pound with low interest rate loans. An agreement was reached to devalue the pound versus the dollar in order to boost UK competitiveness, help create a two-way currency market, and speed up a return to convertibility.[55] In September 1949, the pound was devalued by 30% versus the dollar. Competitiveness returned, the current account improved, and by the mid-to-late 1950s, full convertibility was restored.[56] The charts below On the following pages we will cover in greater detail the specific stages of this decline, firstly with the convertibility crisis of 1947 and the 1949 devaluation, secondly with the gradual evolution of the pound’s status relative to the dollar through the 1950s and early 1960s, and thirdly with the balance of payments crisis of 1967 and subsequent devaluation. We will focus in on the currency crises. 1) The Pound’s Suspended Convertibility in 1946 and Its Devaluation in 1949The 1940s are frequently referred to as “crisis years”[43] for sterling. The war required the UK to borrow immensely from its allies and colonies,[44]and those obligations were required to be held in sterling. These war debts financed about a third of the war effort. When the war ended, the UK could not meet its debt obligations without the great pain of raising taxes or cutting government spending, so it necessarily mandated that its debt assets (i.e., its bonds) could not be proactively sold by its former colonies. As such, the UK emerged from World War II with strict controls on foreign exchange. The Bank of England’s approval was required to convert pounds into dollars, whether to buy US goods or purchase US financial assets (i.e., current and capital account convertibility was suspended). To ensure the pound would function as an international reserve currency in the post-war era, and to prepare the global economy for a transition to the Bretton Woods monetary system, convertibility would have to be restored. However, because the US dollar was now the international currency of choice, the global economy was experiencing a severe shortage of dollars at the time. Virtually all Sterling Area countries (the UK and the Commonwealth countries) relied on inflows from selling goods and services and from attracting investments in dollars to get the dollars they needed while they were forced to hold their sterling-denominated bonds. The UK experienced acute balance of payments problems due to its poor external competitiveness, a domestic fuel crisis, and large war debts undermining faith in the pound as a storehold of wealth. As a result, the first effort to restore convertibility in 1947 failed completely, and it was soon followed by a large devaluation (of 30%) in 1949, to restore some competitiveness.[45]Coming into the period, there were concerns that too quick a return to convertibility would result in a run on the pound, as savers and traders shifted to holding and transacting in dollars all at once. However, the US was anxious for the UK to restore convertibility as soon as possible as restrictions on convertibility were reducing US export profits and reducing liquidity in the global economy.[46] The Bank of England was also eager to remove capital controls in order to restore the pound’s role as a global trading currency, increase financial sector revenues in London, and encourage international investors to continue saving in sterling [47] (a number of governments of European creditors, including Sweden, Switzerland, and Belgium, were having increasing conflicts with the UK over the lack of convertibility).[48] An agreement was reached after the war, under which the UK would reintroduce convertibility swiftly, and the US would provide the UK with a loan of $3.75 billion [49] (about 10% of UK GDP). While the loan offered some buffer against a potential run on the pound, it did not change the underlying imbalances in the global economy. When partial convertibility was introduced in July 1947, the pound came under considerable selling pressure. As the UK and US governments were against devaluation (as memories of the competitive devaluations in the 1930s were fresh on everyone’s minds), [50] the UK and other Sterling Area countries turned to austerity and reserve sales to maintain the peg to the dollar. Restrictions were imposed on the import of “luxury goods” from the US, defense expenditure was slashed, dollar and gold reserves were drawn down, and agreements were made between sterling economies not to diversify their reserve holdings to the dollar.[51] Prime Minister Clement Attlee gave a dramatic speech on August 6, 1947, calling for the spirit of wartime sacrifices to be made once again in order to defend the pound: “In 1940 we were delivered from mortal peril by the courage, skill, and self-sacrifice of a few. Today we are engaged in another battle for Britain. This battle cannot be won by the few. It demands a united effort by the whole nation. I am confident that this united effort will be forthcoming and that we shall again conquer.”[52]Immediately following the speech, the run on the pound accelerated. Over the next five days, the UK had to spend down $175 million of reserves to defend the peg.[53] By the end of August, convertibility was suspended, much to the anger of the US and other international investors who had bought up sterling assets in the lead-up to convertibility hoping that they would soon be able to convert those holdings to dollars. The governor of the National Bank of Belgium even threatened to stop transacting in sterling, requiring a diplomatic intervention.[54]The devaluation came two years later, as policy makers in both the UK and the US realized that the pound couldn’t return to convertibility at the current rate. UK exports were not competitive enough in global markets to earn the foreign exchange needed to support the pound, reserves were dwindling, and the US was unwilling to continue shoring up the pound with low interest rate loans. An agreement was reached to devalue the pound versus the dollar in order to boost UK competitiveness, help create a two-way currency market, and speed up a return to convertibility.[55] In September 1949, the pound was devalued by 30% versus the dollar. Competitiveness returned, the current account improved, and by the mid-to-late 1950s, full convertibility was restored.[56] The charts below  The currency move, which devalued sterling debt, did not lead to a panic out of sterling debt as much as one might have expected especially in light of how bad the fundamentals for sterling debt remained. That is because a very large share of UK assets was held by the US government, which was willing to take the valuation hit in order to restore convertibility, and by Sterling Area economies, such as India and Australia, whose currencies were pegged to the pound for political reasons.[57] These Commonwealth economies, for geopolitical reasons, supported the UK’s decision and followed by devaluing their own currencies versus the dollar, which lessened the visibility of the loss of wealth from the devaluation. Still, the immediate post-war experience made it clear to knowledgeable observers that the pound was vulnerable to more weakness and would not be able to enjoy the same international role it had prior to World War II.1) The Failed International Efforts to Support the Pound in the 1950s and 1960s and the Devaluation of 1967Though the devaluation helped in the short term, over the next two decades, the pound would face recurring balance of payments strains. These strains were very concerning to international policy makers who feared that a collapse in the value of sterling or a rapid shift away from the pound to the dollar in reserve holdings could prove highly detrimental to the new Bretton Woods monetary system (particularly given the backdrop of the Cold War and concerns around communism). As a result, numerous arrangements were made to try to shore up the pound and preserve its role as a source of international liquidity. These included the Bilateral Concerté (1961-64), in which major developed world central banks gave support to countries via the Bank of International Settlements, including multiple loans to the UK and the BIS Group Arrangement 1 (1966-71), which provided swaps to the UK to offset future pressure from potential falls in sterling reserve holdings.[58]In addition to these wider efforts, the UK’s status as the head of the Sterling Area let it mandate that all trade within the Sterling Area would continue to be denominated in pounds and all their currencies would be pegged to sterling. As these economies had to maintain a peg to the pound, they continued to accumulate FX reserves in sterling well after other economies had stopped doing so (e.g., Australia kept 90% of its reserves in sterling as late as 1965).[59] Foreign loans issued in the UK during the period were also almost exclusively to the Sterling Area. The result of all this is that for the 1950s and early 1960s, the UK is best understood as a regional economic power and sterling as a regional reserve currency.[60] Yet all these measures didn’t fix the problem that the UK owed too much money and was uncompetitive, so it didn’t earn enough money to both pay its debts and pay for what it needed to import. Rearrangements were essentially futile stop-gap measures designed to hold back the changing tide. They helped keep the pound stable between 1949 and 1967. Still, sterling needed to be devalued again in 1967. By the mid-1960s, the average share of central bank reserves held in pounds had fallen to around 20%, while international trade was overwhelmingly denominated in dollars (about half). However, many emerging markets and Sterling Area countries continued to hold about 50% of their reserves in pounds and continued to denominate much of their trade with each other and the UK in sterling. This effectively ended following a series of runs on the pound in the 1960s. As in many other balance of payments crises, policy makers used a variety of means to try to maintain the currency peg to the dollar, including spending down reserves, raising rates, and using capital controls. In the end they were unsuccessful, and after the UK devalued by 14% versus the dollar in 1967, even Sterling Area countries were unwilling to hold their reserves in pounds, unless the UK guaranteed their underlying value in dollars.Throughout the 1960s, the UK was forced to defend the peg to the dollar by selling about half of its FX reserve holdings and keeping rates higher than the rest of the developed world—even though the UK economy was underperforming. In both 1961 and 1964, the pound came under intense selling pressure, and the peg was only maintained by a sharp rise in rates, a rapid acceleration in reserve sales, and the extension of short-term credits from the US and the Bank of International Settlements. By 1966, attempts to defend the peg were being described by prominent British policy makers as “a sort of British Dien Bien Phu.”[61] When the pound came under extreme selling pressure again in 1967 (following rising rates in the developed world, recessions in major UK export markets, and heightened conflict in the Middle East),[62] British policy makers decided to devalue sterling by 14% against the dollar. The currency move, which devalued sterling debt, did not lead to a panic out of sterling debt as much as one might have expected especially in light of how bad the fundamentals for sterling debt remained. That is because a very large share of UK assets was held by the US government, which was willing to take the valuation hit in order to restore convertibility, and by Sterling Area economies, such as India and Australia, whose currencies were pegged to the pound for political reasons.[57] These Commonwealth economies, for geopolitical reasons, supported the UK’s decision and followed by devaluing their own currencies versus the dollar, which lessened the visibility of the loss of wealth from the devaluation. Still, the immediate post-war experience made it clear to knowledgeable observers that the pound was vulnerable to more weakness and would not be able to enjoy the same international role it had prior to World War II.1) The Failed International Efforts to Support the Pound in the 1950s and 1960s and the Devaluation of 1967Though the devaluation helped in the short term, over the next two decades, the pound would face recurring balance of payments strains. These strains were very concerning to international policy makers who feared that a collapse in the value of sterling or a rapid shift away from the pound to the dollar in reserve holdings could prove highly detrimental to the new Bretton Woods monetary system (particularly given the backdrop of the Cold War and concerns around communism). As a result, numerous arrangements were made to try to shore up the pound and preserve its role as a source of international liquidity. These included the Bilateral Concerté (1961-64), in which major developed world central banks gave support to countries via the Bank of International Settlements, including multiple loans to the UK and the BIS Group Arrangement 1 (1966-71), which provided swaps to the UK to offset future pressure from potential falls in sterling reserve holdings.[58]In addition to these wider efforts, the UK’s status as the head of the Sterling Area let it mandate that all trade within the Sterling Area would continue to be denominated in pounds and all their currencies would be pegged to sterling. As these economies had to maintain a peg to the pound, they continued to accumulate FX reserves in sterling well after other economies had stopped doing so (e.g., Australia kept 90% of its reserves in sterling as late as 1965).[59] Foreign loans issued in the UK during the period were also almost exclusively to the Sterling Area. The result of all this is that for the 1950s and early 1960s, the UK is best understood as a regional economic power and sterling as a regional reserve currency.[60] Yet all these measures didn’t fix the problem that the UK owed too much money and was uncompetitive, so it didn’t earn enough money to both pay its debts and pay for what it needed to import. Rearrangements were essentially futile stop-gap measures designed to hold back the changing tide. They helped keep the pound stable between 1949 and 1967. Still, sterling needed to be devalued again in 1967. By the mid-1960s, the average share of central bank reserves held in pounds had fallen to around 20%, while international trade was overwhelmingly denominated in dollars (about half). However, many emerging markets and Sterling Area countries continued to hold about 50% of their reserves in pounds and continued to denominate much of their trade with each other and the UK in sterling. This effectively ended following a series of runs on the pound in the 1960s. As in many other balance of payments crises, policy makers used a variety of means to try to maintain the currency peg to the dollar, including spending down reserves, raising rates, and using capital controls. In the end they were unsuccessful, and after the UK devalued by 14% versus the dollar in 1967, even Sterling Area countries were unwilling to hold their reserves in pounds, unless the UK guaranteed their underlying value in dollars.Throughout the 1960s, the UK was forced to defend the peg to the dollar by selling about half of its FX reserve holdings and keeping rates higher than the rest of the developed world—even though the UK economy was underperforming. In both 1961 and 1964, the pound came under intense selling pressure, and the peg was only maintained by a sharp rise in rates, a rapid acceleration in reserve sales, and the extension of short-term credits from the US and the Bank of International Settlements. By 1966, attempts to defend the peg were being described by prominent British policy makers as “a sort of British Dien Bien Phu.”[61] When the pound came under extreme selling pressure again in 1967 (following rising rates in the developed world, recessions in major UK export markets, and heightened conflict in the Middle East),[62] British policy makers decided to devalue sterling by 14% against the dollar. After the devaluation little faith remained in the pound as the second-best reserve currency after the dollar. For the first time since the end of World War II, international central banks began actively selling their sterling reserves (as opposed to simply accumulating fewer pounds in new reserve holdings) and instead began buying dollars, deutschmarks, and yen. As you can see in the chart below on the left, the average share of sterling in central bank reserve holdings collapsed within two years of the devaluation. At the same time the UK was still able to convince Sterling Area countries not to diversify away from the pound. In the Sterling Agreement of 1968, Sterling Area members agreed to maintain a floor on their pound reserve holdings, as long as 90% of the dollar value of these holdings was guaranteed by the British government. So although the share of pound reserves in these Sterling Agreement countries like Australia and New Zealand remained high, this was only because these reserves had their value guaranteed by the British in dollars. So all countries that continued to hold a high share of their reserves in pounds after 1968 were holding de facto dollars with the British bearing the risk of a further sterling devaluation.[63] After the devaluation little faith remained in the pound as the second-best reserve currency after the dollar. For the first time since the end of World War II, international central banks began actively selling their sterling reserves (as opposed to simply accumulating fewer pounds in new reserve holdings) and instead began buying dollars, deutschmarks, and yen. As you can see in the chart below on the left, the average share of sterling in central bank reserve holdings collapsed within two years of the devaluation. At the same time the UK was still able to convince Sterling Area countries not to diversify away from the pound. In the Sterling Agreement of 1968, Sterling Area members agreed to maintain a floor on their pound reserve holdings, as long as 90% of the dollar value of these holdings was guaranteed by the British government. So although the share of pound reserves in these Sterling Agreement countries like Australia and New Zealand remained high, this was only because these reserves had their value guaranteed by the British in dollars. So all countries that continued to hold a high share of their reserves in pounds after 1968 were holding de facto dollars with the British bearing the risk of a further sterling devaluation.[63] [64]By this time the dollar was having its own set of balance of payments and currency problems, but that is for the next installment of this series when I turn to the United States and China. [1] We show where key indicators were relative to their history by averaging them across the cases. The chart is shown such that a value of “1” represents the peak in that indicator relative to history and “0” represents the trough. The timeline is shown in years with “0” representing roughly when the country was at its peak (i.e., when the average across gauges was at its peak). In the rest of this section, we walk through each of the stages of the archetype in more detail. While the charts show the countries that produced global reserve currencies, we’ll also heavily reference China, which was a dominant empire for centuries, though it never established a reserve currency.[2] A good example of this is the popularity of the Patriot movement in the Netherlands around this time: Encyclopedia Britannica, The Patriot movement, https://www.britannica.com/place/Netherlands/The-18th-century#ref414139[3] While most people think that the ascent of the US came after World War II, it really started here and went on across both wars—and the seeds of that rise came still earlier from the self-reinforcing upswings in US education, innovation, competitiveness, and economic outcomes over the 19th century.[4] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[5] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[6] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[7] In this piece, when talking about “the guilder,” we generally refer to guilder bank notes, which were used at the Bank of Amsterdam, rather than the physical coin (also called “guilder”).[8] Encyclopedia Britannica, Eighty Years’ War, https://www.britannica.com/event/Eighty-Years-War[9] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[10] Israel, Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585-1740, 219[11] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[12] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Dutch War, https://www.britannica.com/event/Dutch-War[13] Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806, 824-825[14] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[15] There was a general rise in foreign investment by the Dutch during this period. Investments in UK assets offered high real returns. Examples include Dutch purchases of stocks in the British East India Company, and the City of London selling term annuities (bonds) to Dutch investors. For a further description, see Hart, Jonker, and van Zanden, A Financial History of the Netherlands, 56-58.[16] Hart, Jonker, and van Zanden, A Financial History of the Netherlands, 20-21[17] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 13 [18] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[19] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[20] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[21] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455[22] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 126[23] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 685-686[24] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455[25] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455-456 & https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[26] This chart only shows the financial results from the Dutch East India Company reported “in patria,” e.g., the Netherlands. It does not include the part of the revenue and debt from its operations in Asia but does include its revenues from goods it retrieved in Asia and sold in Europe.[27] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 17[28] “Guilder” in this case refers to devaluing bank deposits in guilder from the Bank of Amsterdam, not physical coin. For details on the run, see Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16.[29] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 17-18[30] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16[31] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 34[32] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 15-16[33] The Bank of Amsterdam was ahead its time and used ledgers instead of real “paper money.” See Quinn & Roberds, “The Bank of Amsterdam Through the Lens of Monetary Competition,” 2[34] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 19, 26[35] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 19-20[36] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16[37] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 24[38] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 685-686[39] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Dutch East India Company, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dutch-East-India-Company; also see de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 463-464[40] Historical data suggests that by 1795, bank deposits were trading at a -25% discount to actual coin. Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 26.[41] Note: To fully represent the likely economics of a deposit holder at the Bank of Amsterdam, we assumed depositors each received their pro-rated share of precious metal still in the bank’s vaults when it was closed (that was roughly 20% of the fully backed amount, thus the approximately 80% total devaluation).[42] Gelderblom & Jonker, “Exporing the Market for Government Bonds in the Dutch Republic (1600-1800),” 16[43] For example, see Catherine Schenk, The Decline of Sterling: Managing the Retreat of an International Currency, 1945–1992, 37 (hereafter referred to as Schenk, Decline of Sterling)[44] See Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 39[45] For an overview of the convertibility crisis and devaluation, see Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 68-80; Alec Cairncross & Barry Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline: The Devaluations of 1931, 1949, and 1967, 102-147 (hereafter referred to as Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline).[46] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 44[47] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 31[48] Alex Cairncross, Years of Recovery: British Economic Policy 1945-51, 124-126[49] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 63[50] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 48[51] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 62[52] As quoted in Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 62-63[53] Ibid[54] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 66-67[55] For more detail, see Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline, 139-155[56] See also Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline, 151-155 for a discussion of other contributing factors[57] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 39, 46; for further description, see https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-sterling-area/[58] For further description of these and other coordinated policies, see Catherine Schenk, “The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency After 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?”[59] John Singleton & Catherine Schenk, “The Shift from Sterling to the Dollar, 1965–76: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand,” 1162[60] For more detail on the dynamics of the Sterling Area, see Catherine Schenk, Britain and the Sterling Area, 1994[61] As quoted by Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 156[62] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 174[63] For fuller coverage of this, see Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 273-315[64] Data from Schenk, “The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency After 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?,” 25DisclosuresBridgewater Daily Observations is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Capital Economics, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., CoStar Realty Information, Inc., CreditSights, Inc., Dealogic LLC, DTCC Data Repository (U.S.), LLC, Ecoanalitica, EPFR Global, Eurasia Group Ltd., European Money Markets Institute – EMMI, Evercore ISI, Factset Research Systems, Inc., The Financial Times Limited, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Haver Analytics, Inc., ICE Data Derivatives, IHSMarkit, The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, International Energy Agency, Lombard Street Research, Mergent, Inc., Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s Analytics, Inc., MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Renwood Realtytrac, LLC, Rystad Energy, Inc., S&P Global Market Intelligence Inc., Sentix Gmbh, Spears & Associates, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust Company, Sun Hung Kai Financial (UK), Refinitiv, Totem Macro, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Wind Information (Shanghai) Co Ltd, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, and World Economic Forum. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues. [64]By this time the dollar was having its own set of balance of payments and currency problems, but that is for the next installment of this series when I turn to the United States and China. [1] We show where key indicators were relative to their history by averaging them across the cases. The chart is shown such that a value of “1” represents the peak in that indicator relative to history and “0” represents the trough. The timeline is shown in years with “0” representing roughly when the country was at its peak (i.e., when the average across gauges was at its peak). In the rest of this section, we walk through each of the stages of the archetype in more detail. While the charts show the countries that produced global reserve currencies, we’ll also heavily reference China, which was a dominant empire for centuries, though it never established a reserve currency.[2] A good example of this is the popularity of the Patriot movement in the Netherlands around this time: Encyclopedia Britannica, The Patriot movement, https://www.britannica.com/place/Netherlands/The-18th-century#ref414139[3] While most people think that the ascent of the US came after World War II, it really started here and went on across both wars—and the seeds of that rise came still earlier from the self-reinforcing upswings in US education, innovation, competitiveness, and economic outcomes over the 19th century.[4] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[5] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[6] Rough estimate based on internal calculations[7] In this piece, when talking about “the guilder,” we generally refer to guilder bank notes, which were used at the Bank of Amsterdam, rather than the physical coin (also called “guilder”).[8] Encyclopedia Britannica, Eighty Years’ War, https://www.britannica.com/event/Eighty-Years-War[9] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[10] Israel, Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585-1740, 219[11] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[12] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Dutch War, https://www.britannica.com/event/Dutch-War[13] Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806, 824-825[14] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[15] There was a general rise in foreign investment by the Dutch during this period. Investments in UK assets offered high real returns. Examples include Dutch purchases of stocks in the British East India Company, and the City of London selling term annuities (bonds) to Dutch investors. For a further description, see Hart, Jonker, and van Zanden, A Financial History of the Netherlands, 56-58.[16] Hart, Jonker, and van Zanden, A Financial History of the Netherlands, 20-21[17] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 13 [18] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[19] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[20] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Anglo-Dutch Wars, https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[21] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455[22] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 126[23] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 685-686[24] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455[25] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 455-456 & https://www.britannica.com/event/Anglo-Dutch-Wars[26] This chart only shows the financial results from the Dutch East India Company reported “in patria,” e.g., the Netherlands. It does not include the part of the revenue and debt from its operations in Asia but does include its revenues from goods it retrieved in Asia and sold in Europe.[27] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 17[28] “Guilder” in this case refers to devaluing bank deposits in guilder from the Bank of Amsterdam, not physical coin. For details on the run, see Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16.[29] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 17-18[30] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16[31] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 34[32] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 15-16[33] The Bank of Amsterdam was ahead its time and used ledgers instead of real “paper money.” See Quinn & Roberds, “The Bank of Amsterdam Through the Lens of Monetary Competition,” 2[34] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 19, 26[35] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 19-20[36] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 16[37] Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 24[38] de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 685-686[39] Encyclopedia Britannica, The Dutch East India Company, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dutch-East-India-Company; also see de Vries & van der Woude, The First Modern Economy, 463-464[40] Historical data suggests that by 1795, bank deposits were trading at a -25% discount to actual coin. Quinn & Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” 26.[41] Note: To fully represent the likely economics of a deposit holder at the Bank of Amsterdam, we assumed depositors each received their pro-rated share of precious metal still in the bank’s vaults when it was closed (that was roughly 20% of the fully backed amount, thus the approximately 80% total devaluation).[42] Gelderblom & Jonker, “Exporing the Market for Government Bonds in the Dutch Republic (1600-1800),” 16[43] For example, see Catherine Schenk, The Decline of Sterling: Managing the Retreat of an International Currency, 1945–1992, 37 (hereafter referred to as Schenk, Decline of Sterling)[44] See Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 39[45] For an overview of the convertibility crisis and devaluation, see Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 68-80; Alec Cairncross & Barry Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline: The Devaluations of 1931, 1949, and 1967, 102-147 (hereafter referred to as Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline).[46] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 44[47] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 31[48] Alex Cairncross, Years of Recovery: British Economic Policy 1945-51, 124-126[49] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 63[50] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 48[51] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 62[52] As quoted in Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 62-63[53] Ibid[54] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 66-67[55] For more detail, see Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline, 139-155[56] See also Cairncross & Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline, 151-155 for a discussion of other contributing factors[57] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 39, 46; for further description, see https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-sterling-area/[58] For further description of these and other coordinated policies, see Catherine Schenk, “The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency After 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?”[59] John Singleton & Catherine Schenk, “The Shift from Sterling to the Dollar, 1965–76: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand,” 1162[60] For more detail on the dynamics of the Sterling Area, see Catherine Schenk, Britain and the Sterling Area, 1994[61] As quoted by Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 156[62] Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 174[63] For fuller coverage of this, see Schenk, Decline of Sterling, 273-315[64] Data from Schenk, “The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency After 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?,” 25DisclosuresBridgewater Daily Observations is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Capital Economics, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., CoStar Realty Information, Inc., CreditSights, Inc., Dealogic LLC, DTCC Data Repository (U.S.), LLC, Ecoanalitica, EPFR Global, Eurasia Group Ltd., European Money Markets Institute – EMMI, Evercore ISI, Factset Research Systems, Inc., The Financial Times Limited, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Haver Analytics, Inc., ICE Data Derivatives, IHSMarkit, The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, International Energy Agency, Lombard Street Research, Mergent, Inc., Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s Analytics, Inc., MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Renwood Realtytrac, LLC, Rystad Energy, Inc., S&P Global Market Intelligence Inc., Sentix Gmbh, Spears & Associates, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust Company, Sun Hung Kai Financial (UK), Refinitiv, Totem Macro, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Wind Information (Shanghai) Co Ltd, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, and World Economic Forum. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.