-

Recent Posts

- More about Light Root

- What to tell my doctor about imuno™

- Seeking aspiring seed steward: Heirloom Seed collection for sale

- How does Bravo work? What did I experience? How can we help to support it? The undesirable truth.

- “Stress-resilience impacts psychological wellbeing as evidenced by brain–gut microbiome interactions”

Categories

Products

Research from a talk given by Dr. Marco Ruggiero

Furin, a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19

Potential treatment of Chinese and Western Medicine targeting nsp14 of 2019-nCoV

Clinical remission of a critically ill COVID-19 patient treated by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

Transplantation of ACE2- mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

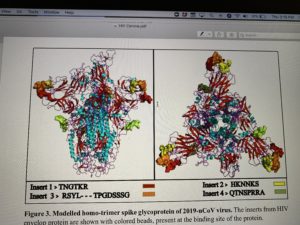

Uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag

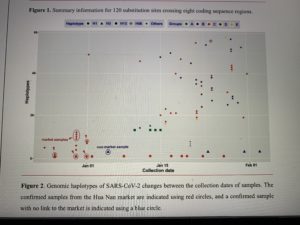

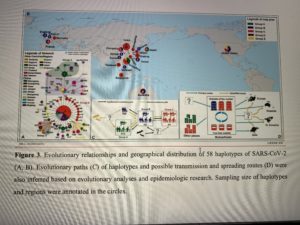

Decoding the evolution and transmissions of the novel pneumonia coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) using whole genomic data

Posted in Most Recent

2 Comments

Transplantation of ACE2- mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

Transplantation of ACE2– mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

Zikuan Leng1,5#, Rongjia Zhu2#, Wei Hou3#, Yingmei Feng3#, Yanlei Yang4, Qin Han2, Guangliang Shan2, Fanyan Meng1, Dongsheng Du1, Shihua Wang2, Junfen Fan2, Wenjing Wang3, Luchan Deng2, Hongbo Shi3, Hongjun Li3, Zhongjie Hu3, Fengchun Zhang4, Jinming Gao4, Hongjian Liu5*, Xiaoxia Li6, Yangyang Zhao2, Kan Yin6, Xijing He7, Zhengchao Gao7, Yibin Wang7, Bo Yang8, Ronghua Jin3*, Ilia Stambler9,10,11, Kunlin Jin9,10,12*, Lee Wei Lim9,10,13, Huanxing Su9,10,14, Alexey Moskalev9,10,15, Antonio Cano9,10,16, Sasanka Chakrabarti9,10,17, Armand Keating9.10,18, Kyung-Jin Min9,10,19, Georgina Ellison-Hughes9,10,20, Calogero Caruso9,10,21, Robert Chunhua Zhao1,2,9,10*

1School of Life Sciences, Shanghai University, Shanghai, 200444, China

2Institute of Basic Medical Sciences Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, School of Basic Medicine Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100005, China

3Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

4Department of Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

5Department of Orthopaedics, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

6Institute of Stem Cell and Regeneration Medicine, School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong, China

7Department of Orthopaedics, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

8Department of Neurosurgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

9The Executive Committee on Anti-aging and Disease Prevention in the framework of Science and Technology, Pharmacology and Medicine Themes under an Interactive Atlas along the Silk Roads, UNESCO, Paris, France

10International Society on Aging and Disease (ISOAD), Fort Worth, Texas, USA

11The Geriatric Medical Center “Shmuel Harofe”, Beer Yaakov, affiliated to Sackler School of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

12University of North Texas Health Science Center, Fort Worth, TX, USA

13School of Biomedical Sciences, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

14Institute of Chinese Medical Science, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China 15Laboratory of Geroprotective and Radioprotective Technologies,

Institute of Biology, Komi Science Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Syktyvkar, Russia 16Department of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain 17Department of Biochemistry, Maharishi Markandeshwar University, Kolkata, India

1

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

18Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

19Department of Biological Sciences, Inha University, Incheon, South Korea

20Centre of Human & Aerospace Physiological Sciences & Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK

21Laboratory of Immunopathology and Immunosenescence, Department of Biomedicine, Neuroscience and Advanced Diagnostics, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy

#These authors contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding authors:

Robert Chunhua Zhao, M.D. & Ph.D., Professor, School of Life Sciences, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China. Email: zhaochunhua@vip.163.com

Kunlin Jin, M.D. & Ph.D., Professor, University of North Texas Health Science Center, Fort Worth, TX, 76107, USA. kunlin.Jin@unthsc.edu

Ronghua Jin, M.D. & Ph.D., Professor, You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. Email: jin_eagle@sina.com

Hongjian Liu, M.D. & Ph.D., Professor, Department of Orthopaedics, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China. Email: hongjianmd@126.com

2

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Abstract

A coronavirus (HCoV-19) has caused the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, China, Preventing and reversing the cytokine storm may be the key to save the patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been shown to possess a comprehensive powerful immunomodulatory function. This study aims to investigate whether MSC transplantation improve the outcome of 7 enrolled patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Beijing YouAn Hospital, China from Jan 23, 2020. to Feb 16, 2020. The clinical outcomes, as well as changes of inflammatory and immune function levels and adverse effects of 7 enrolled patients were assessed for 14 days after MSC injection. MSCs could cure or significantly improve the functional outcomes of seven patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in 14 days without observed adverse effect. The pulmonary function and symptoms of all patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were significantly improved in 2 days after MSC transplantation. Among them, two common and one severe patient were recovered and discharged in 10 days after treatment. After treatment, the peripheral lymphocytes were increased and the overactivated cytokine-secreting immune cells CXCR3+CD4+ T cells, CXCR3+CD8+ T cells, and CXCR3+ NK cells were disappeared in 3-6 days. And a group of CD14+CD11c+CD11bmid regulatory DC cell population dramatically increased. Meanwhile, the level TNF-α is significantly decreased while IL-10 increased in MSC treatment group compared to the placebo control group. Furthermore, the gene expression profile showed MSCs were ACE2- and TMPRSS2- which indicated MSCs are free from COVID-19 infection. Thus, the intravenous transplantation of MSCs was safe and effective for treatment in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, especially for the patients in critically severe condition.

Key words

COVID-19, ACE2 negative, mesenchymal stem cells, cell transplantation, immunomodulatory, function recovery

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has grown to be a global public health emergency since patients were first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Since then, the number of COVID-19 confirmed patients have sharply increased not only in China, but also worldwide, including Germany, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, and USA[1]. Currently, no specific drugs or vaccines are available to cure the patients with COVID-19 infection. Hence, there is a large unmet need for a safe and effective treatment for COVID-19 infected patients, especially the severe cases.

Several reports demonstrated that the first step of the HCoV-19 pathogenesis is that the virus specifically recognizes the angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2) by its spike protein[2-4]. ACE2-positive cells are infected by the HCoV-19, like SARS-2003[5,6]. In addition, a research team from Germany revealed that the cellular serine protease TMPRSS2 for HCoV-19 Spike protein priming is also essential for the host cell entry and spread[7], like

3

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

the other coronavirus (i.e. SARS-2003)[8,9]. Unfortunately, the ACE2 receptor is widely distributed on the human cells surface, especially the alveolar type II cells (AT2) and capillary endothelium[10], and the AT2 cells highly express TMPRSS2[9]. However, in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, thymus, and the spleen, immune cells, such as T and B lymphocytes, and macrophages are consistently negative for ACE2[10]. The findings suggest that immunological therapy may be used to treat the infected patients. However, the immunomodulatory capacity may be not strong enough, if only one or two immune factors were used, as the virus can stimulate a terrible cytokine storm in the lung, such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, GSCF, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα, followed by the edema, dysfunction of the air exchange, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute cardiac injury and the secondary infection[11], which may led to death. Therefore, avoiding the cytokine storm may be the key for the treatment of HCoV-19 infected patients. MSCs, owing to their powerful immunomodulatory ability, may have beneficial effects on preventing or attenuating the cytokine storm.

MSCs have been widely used in cell-based therapy, from basic research to clinical trials[12,13]. Safety and effectiveness have been clearly documented in many clinical trials, especially in the immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as graft versus-host disease (GVHD)[14] and systemic lypus erythematosus (SLE)[15]. MSCs play a positive role mainly in two ways, namely immunomodulatory effects and differentiation abilities[16]. MSCs can secrete many types of cytokines by paracrine secretion or make direct interactions with immune cells, leading to immunomodulation[17]. The immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are triggered further by the activation of TLR receptor in MSCs, which is stimulated by pathogen-associated molecules such as LPS or double-stranded RNA from virus[18,19], like the HCoV-19.

Here we conducted an MSC transplantation pilot study to explore their therapeutic potential for HCoV-19 infected patients. In addition, we also explored the underlying mechanisms using a 10× Genomics high throughput RNA sequencing clustering analysis on MSCs and mass cytometry.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A pilot trial of intravenous MSC transplantation was performed on seven patients with COVID-19 infected pneumonia. The study was conducted in Beijing YouAn Hospital, Capital Medical University, China, and approved by the ethics committee of the hospital (LL-2020- 013-K). The safety and scientific validity of this study “Clinical trials of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of pneumonitis caused by novel coronavirus” from Shanghai University/ PUMC have been reviewed by the scientific committee at International Society on Aging and Disease (ISOAD) and issued in Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000029990).

The Patients

The patients were enrolled from Jan 23, 2020 to Jan 31, 2020. All enrolled patients were

4

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

confirmed by the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay of HCoV-19 RNA in Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention using the protocol as described previously[11,20]. The sequences were as follows: forward primer 5′-

TCAGAATGCCAATCTCCCCAAC-3′; reverse AAAGGTCCACCCGATACATTGA-3′; andCTAGTTACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGC-3′BHQ1.

We initially enrolled patients with COVID-19 (age 18–95 years) according to the guidance of National Health and Health Commission of China (Table 1).

If no improvement signs were observed under the standard treatments, the patient would be suggested to receive the MSC transplantation. Patients were ineligible if they had been diagnosed with any kind of cancers or the doctor declared the situation to belong to the critically severe condition. We excluded patients who were participating in other clinical trials or who have participated in other clinical trials within 3 months.

Cell preparation and transplantation

The clinical grade MSCs were supplied, for free, by Shanghai University, Qingdao Co-orient Watson Biotechnology group co. LTD and the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The cell product has been certified by the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control of China (authorization number: 2004L04792,2006L01037,CXSB1900004). Before the intravenous drip, MSCs were suspended in 100 ml of normal saline, and the total number of transplanted cells was calculated by 1 × 106 cells per kilogram of weight. The window period for cell transplantation was defined as the time when symptoms or/and signs still were getting worse even as the expectant treatments were being conducted. The injection was performed about forty minutes with a speed of ~40 drops per minute.

The patients were assessed by the investigators through the 14-day observation after receiving the investigational product. The clinical, laboratory, and radiological outcomes were recorded and certified by a trained group of doctors. The detailed record included primary safety data (infusional and allergic reactions, secondary infection and life-threatening adverse events) and the primary efficacy data (the level of the cytokines variation, the level of C-reactive protein in plasma and the oxygen saturation). The secondary efficacy outcomes mainly included the total lymphocyte count and subpopulations, the chest CT, the respiratory rate, and the patient symptoms (especially the fever and shortness of breath). In addition, the therapeutic measures (i.e. antiviral medicine and respiratory support) and outcomes were also examined.

Statistical analysis

MIMICS 21.0 (Interactive medical image control system of Materialise, Belgium) was used to evaluate the chest CT data. The analysis of Mass cytometry of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells is described in Supplementary Material 1. The analysis of the 10 x RNA-seq survey is described in Supplementary Material 2. Data were analyzed by SPSS software (SPSS 22.0). Differences between two groups were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t tests. Data

5

primer 5′- the probe 5′CY5-

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

involving more than two groups were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

MSC treatment procedure and general patient information

This study was conducted from Jan 23, 2020, to Feb 16, 2020. Seven confirmed COVID-19 patients, including 1 critically severe type (patient 1), 4 severe types (patient 2, 3, 6, 7) and 2 common types (patient 4, 6) were enrolled. The timepoint of MSC transplantation for each patient is as shown in Figure 1. The general information of the 7 patients is listed in Table 1. Hitherto, the critically severe patient had completed the MSC treatment. This patient had a 10- year medical history of hypertension with the highest-level of 180/90 mmHg recorded. All the treatment information of the patients was collected.

Figure 1. The flow chart of the cell transplantation treatment

The primary safety outcome

Before the MSC transplantation, the patients had symptoms of high fever (38.5°C ± 0.5°C), weakness, shortness of breath, and low oxygen saturation. However, 2~4 days after transplantation, all the symptoms were disappeared in all the patients, the oxygen saturations rose to ≥ 95% at rest, without or with oxygen uptake (5 liters per minute). In addition, no acute infusion-related or allergic reactions were observed within two hours after transplantation. Similarly, no delayed hypersensitivity or secondary infections were detected after treatment. The detailed diagnosis and treatment procedures of the critically severe patient are shown in Supplementary Material 3. The main symptoms and signs are shown in Table 3.

6

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

The efficacy outcome

The immunomodulating function of MSCs contributed to the main efficacy outcome and the transplantation of MSCs showed impressive positive results (Table 3). For the primary outcome in the critically severe patient 1, the plasma C-reaction protein level decreased from 105.5 g/L (Jan 30) to 10.1 g/L (Feb 13), which reached the highest level of 191.0 g/L on Feb 1, indicating that the inflammation status was alleviating quickly. The oxygen saturation, without Supplementary oxygen, rose from 89% (Jan 31) to 98% (Feb 13), which indicated the pulmonary alveoli regained the air-change function.

The secondary outcomes were also improved (Table 4). Considering, for example, the critically severe patient 1, the lymphopenia was significantly improved after the cell transplantation. The patient was isolated in the hospital isolation ward with a history of hypertension and blood pressure reaching grade 3 hypertension. On Feb 1, biochemical indicators in the blood test showed that aspartic aminotransferase, creatine kinase activity and myoglobin increased sharply to 57 U/L, 513 U/L, and 138 ng/ml, respectively, indicating severe damage to the liver and myocardium. However, the levels of these functional biochemical indicators were decreased to normal reference values in 2~4 days after treatment (Table 4). On February 13, all the indexes reached to normal levels, namely 19 U/L, 40 U/L, and 43 ng/ml, respectively. The respiratory rate was decreased to the normal range on the 4th day after MSC transplantation. Both fever and shortness of breath disappeared on the 4th day after MSCs transplantation. Chest CT imaging showed that the ground-glass opacity and pneumonia infiltration had largely reduced on the 9th day after MSC transplantation (Figure 2).

7

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Figure 2. Chest computerized tomography (CT) images of the critically severe COVID-19 patient. On Jan 23, no pneumonia performance was observed. On Jan 30, ground-glass opacity and pneumonia infiltration occurred in multi-lobes of the double sides. Cell transplantation was performed on Jan 31. On Feb 2, the pneumonia invaded all through the whole lung. On Feb 9, the pneumonia infiltration faded away very much. On Feb 15, only little ground-glass opacity was residual in local.

8

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

HCoV-19 nucleic acid detection

RT-PCR analysis of HCoV-19 nucleic acid was performed before and after MSC transplantation. For the critically severe patient, before transplantation (Jan 23) and 6 days after transplantation (Feb 6), HCoV-19 nucleic acid was positive. 13 days after transplantation (Feb 13), HCoV-19 nucleic acid turned to be negative. The patient 3, 4,5 also turned to be negative result of HCoV- 19 nucleic acid until this report date.

Mass cytometry (CyTOF) analysis of the patients’ peripheral blood

To investigate the profile of the immune system constitution during MSC transplantation, we performed the CyTOF to analyze immune cells in the patients’ peripheral blood before and after transplantation. CyTOF revealed that there was nearly no increase of regulatory T cells (CXCR3-) or dendritic cells (DC, CXCR3-) for the two patients of common type (Patient 4 and 5). But in the severe patients, both the regulatory T cells and DC increased after the cell therapy, especially for the critically severe patient. Notably, no significant CXCR3- DC enhanced after placebo treatment in three severe control patients. Moreover, for the critically severe patient, before the MSC transplantation the percentage of CXCR3+CD4+ T cells, CXCR3+CD8+ T cells, and CXCR3+ NK cells in the patient’s PBMC were remarkably increased compared to the healthy control, which caused the inflammatory cytokine storm. However, 6 days after MSC transplantation, the overactivated T cells and NK cells nearly disappeared and the numbers of the other cell subpopulations were almost restored to the normal levels, especially the CD14+CD11c+CD11bmid regulatory dendritic cell population (Figure 3).

9

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Figure 3. The mass cytometry results of peripheral blood mononuclear cells of the enrolled patients (A, B) and the critically severe patient (C). No increase of regulatory T cells (CXCR3-) or dendritic cells (DC, CXCR3-) for the two patients of common type (Patient 4 and 5, Figrue 3A). But in the severe patients, both the regulatory T cells and DC increased after the cell therapy, especially for the critical severe patient 1 (Figure 3B). Moreover, for the critically severe patient 1, before the MSC transplantation the percentage of overactivated CXCR3+CD4+ T cells (#9), CXCR3+CD8+ T cells (#17), and CXCR3+ NK cells (#12) in the patient’s PBMC were remarkably increased compared to the healthy control (Figure 3C). However, 6 days after MSC transplantation, the overactivated T cells and NK cells nearly disappeared and the numbers of the other cell subsets were almost reversed to the normal levels, especially the CD14+CD11c+CD11bmid DC (#20) population. Normal: health individuals, MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells transplant group, Ctrl: placebo control group.

Serum Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor Analysis

After intravenous injection of MSCs, the decrease ratio of pro-inflammatory cytokine in serum TNF-α before and after MSC treatment was significant (p<0.05). Meanwhile, the increase ratio of anti-inflammatory IL-10 (p<0.05) also showed remarkably in the MSC treatment group. The

10

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

serum levels of chemokines like IP-10 and growth factor VEGF were both increased, though not significantly (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The ratio of serum cytokines IL-10 (A), growth factor VEGF (B), the chemokine IP-10 (C) and TNF-α (D) before and after MSCs treatment were detected in severe patients compared with the control group without MSCs by panel assay analysis, respectively. Ctrl: placebo control group. P-values were determined using the student’s t-test. *P < 0.05.

10 x RNA-seq analysis for transplanted MSCs

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying MSC-mediated protection for COVID-19 infected patients, we performed the 10 x RNA-seq survey for transplanted MSCs. The 10 x RNA-seq survey captured 12,500 MSCs which were then sequenced with 881,215,280 raw reads totally (Supplementary Material 4). The results revealed that MSCs are ACE2 or TMPRSS2 negative, indicating that MSCs are free from COVID-19 infection. Moreover, anti- inflammatory and trophic factors like TGF-β, HGF, LIF, GAL, NOA1, FGF, VEGF, EGF, BDNF, and NGF were highly expressed in MSCs, further demonstrating the immunomodulatory function of MSCs. Moreover, SPA and SPC were highly expressed in MSCs, indicating that MSCs might differentiate to AT2 cells (Figure 5). KEGG pathway analysis showed that MSCs were closely involved in the antiviral pathways (Supplementary Material 4).

11

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Figure 5. The 10 x RNA-seq survey of MSCs genes expression: Both ACE2 (A) and TMPRSS2 (B) were rarely expressed. TGF-β (C), HGF (D), LIF (E), GAL (F), NOA1 (G), FGF (H), VEGF (I), EGF (J), BDNF (K), and NGF (L) were highly expressed, indicating the immunomodulatory function of MSCs. SPA (M) and SPC (N) were highly expressed, indicating MSCs owned the ability to differentiate into the alveolar epithelial cells II. One point represented one cell, and red and gray color showed high expression and low expression,

12

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

respectively.

Discussion

Both the novel coronavirus and SARS-2003 could enter the host cell by binding the S protein on the viral surface to the ACE2 on the cell surface[3,5]. In addition to the lung, ACE2 is widely expressed in human tissues, including the heart, liver, kidney, and digestive organs[10]. In fact, almost all endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in organs express ACE2, therefore once the virus enters the blood circulation, it spreads widely. All tissues and organs expressing ACE2 could be the battlefield of novel coronavirus and immune cells. This explains why not only all infected ICU patients are suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome, but also complications such as acute myocardial injury, arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, shock, and death of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome[11](Figure 6). Moreover, the HCoV-19 is more likely to affect older males with comorbidities and can result in severe and even fatal respiratory diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome[21], like the critically severe case here. However, the cure of COVID-2019 is essentially dependent on the patient’s own immune system. When the overactivated immune system kills the virus, it produces a large amount of inflammatory factors, leading to the severe cytokine storms[20]. It suggests that the main reason of these organs damage may be due to virus-induced cytokine storm. Older subjects may be much easier to be affected due to immunosenescence.

Figure 6. ACE2- MSCs benefit the COVID-19 patients via immunoregulatory function

Our 10x scRNA-seq survey shows that MSCs are ACE2- and TMPRSS2- (to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time to be reported) and secrete anti-inflammatory factors to prevent the cytokine storm. They have the natural immunity to the HCoV-19. According to the mass

13

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

cytometry streaming results, the virus infection caused a total function failure of the lymphocytes, even of the whole immune system. MSCs played the vital immune modulation roles to reverse the lymphocyte subsets mainly through dendritic cells. Our previous study showed that co-culture with MSCs could decrease the differentiation of cDC from human CD34+ cells, while increasing the differentiation of pDC through PGE2[22]. Furthermore, the induction of IL-10–dependent regulatory dendritic cells and IRF8-controlled regulatory dendritic cells from HSC were also reported in rats[23,24]. MSCs could also induce mature dendritic cells into a novel Jagged-2-dependent regulatory dendritic cell population[25]. All these interactions with different dendritic cells led to a shift of the immune system from Th1 toward Th2 responses.

Several reports also focused on lymphopenia and high levels of C-reactive protein in COVID- 19 patients[20,21]. C-reactive protein is a biomarker with high-sensitivity for inflammation and host response to the production of cytokines, particularly TNFα, IL-6, MCP1 and IL-8 secreted by T cells[26]. However, most mechanistic studies suggest that C-reactive protein itself is unlikely to be a target for intervention. C-reactive protein is also a biomarker of myocardial damage[27].

MSC therapy can inhibit the overactivation of the immune system and promote endogenous repair by improving the microenvironment. After entering the human body through intravenous infusion, part of the MSCs accumulate in the lung, which could improve the pulmonary microenvironment, protect alveolar epithelial cells, prevent pulmonary fibrosis and improve lung function.

As reported by Cao’s team[11], the levels of serum IL-2, IL-7, G-SCF, IP10, MCP-1, MIP-1A and TNF-α in ICU patients were higher than those of normal patients. The cytokine release syndrome caused by abnormally activated immune cells deteriorated the patient’s states which may cause disabled function of endothelial cells, the capillary leakage, the mucus block in lung and finally the respiratory failure. And they could cause even an inflammatory cytokine storm lead to multiple organ failure. The administration of intravenous injection of MSCs significantly improved the inflammation situation in severe COVID-19 patients. Due to its unique immunosuppression capacity, the serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were reduced dramatically which attracted less mononuclear/macrophages to fragile lung, while induced more regulatory dendric cells to the inflammatory tissue niche. Moreover, the increased IL-10 and VEGF promoted the lung’s repair. Ultimately, the patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia survived the worst condition and recovery.

Therefore, the fact that transplantation of MSCs improved the outcome of COVID-2019 patients may be through regulating inflammatory response and promoting tissue repair and regeneration.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China

14

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

(2016YFA0101000, 2018YFE0114200), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2017- I2M-3-007) and the 111 Project (B18007), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971324, 81672313, 81700782, 81972523, 81771349).

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1] Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, van Riel D, de Wit E (2020). A Novel Coronavirus Emerging in China — Key Questions for Impact Assessment. New England Journal of Medicine.

- [2] Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, Feng J, Zhou H, Li X, et al. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. SCIENCE CHINA Life Sciences.

- [3] Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. (2020). Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (London, England).

- [4] Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (2020). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature.

- [5] Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao SA, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, et al. (2005). A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nature Medicine, 11:875-879.

- [6] Ge X-Y, Li J-L, Yang X-L, Chmura AA, Zhu G, Epstein JH, et al. (2013). Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature, 503:535- +.

- [7] Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Krüger N, Müller M, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S (2020). The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. bioRxiv:2020.2001.2031.929042.

- [8] Glowacka I, Bertram S, Mueller MA, Allen P, Soilleux E, Pfefferle S, et al. (2011). Evidence that TMPRSS2 Activates the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein for Membrane Fusion and Reduces Viral Control by the Humoral Immune Response. Journal of Virology, 85:4122-4134.

- [9] Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Okamura T, Shimizu Y, Hasegawa H, Takeda M, Nagata N (2019). TMPRSS2 Contributes to Virus Spread and Immunopathology in the Airways of Murine Models after Coronavirus Infection. Journal of Virology, 93.

- [10] Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H (2004). Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. Journal of Pathology, 203:631-637.

- [11] Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet.

- [12] Connick P, Kolappan M, Crawley C, Webber DJ, Patani R, Michell AW, et al. (2012). Autologous mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: an open-label phase 2a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurology, 11:150-156.

15

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

- [13] Wilson JG, Liu KD, Zhuo NJ, Caballero L, McMillan M, Fang XH, et al. (2015). Mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells for treatment of ARDS: a phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 3:24-32.

- [14] Hashmi S, Ahmed M, Murad MH, Litzow MR, Adams RH, Ball LM, et al. (2016). Survival after mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematology, 3:E45-E52.

- [15] Kamen DL, Nietert PJ, Wang H, Duke T, Cloud C, Robinson A, et al. (2018). CT-04 Safety and efficacy of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of an open-label phase I study. Lupus Science & Medicine, 5:A46-A47.

- [16] Galipeau J, Sensebe L (2018). Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Clinical Challenges and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Stem Cell, 22:824-833.

- [17] Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE (2013). Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Sensors and Switchers of Inflammation. Cell Stem Cell, 13:392-402.

- [18] Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, Betancourt AM (2010). A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS One, 5:e10088.

- [19] Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, Su J, Han Y, Li J, et al. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ, 19:1505-1513.

- [20] Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. (2020). Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA.

- [21] Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (2020). Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet (London, England).

- [22] Chen L, Zhang W, Yue H, Han Q, Chen B, Shi M, et al. (2007). Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on the differentiation of dendritic cells from CD34(+) cells. Stem Cells and Development, 16:719-731.

- [23] Liu X, Qu X, Chen Y, Liao L, Cheng K, Shao C, et al. (2012). Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Induce the Generation of Novel IL-10-Dependent Regulatory Dendritic Cells by SOCS3 Activation. Journal of Immunology, 189:1182-1192.

- [24] Liu X, Ren S, Ge C, Cheng K, Zenke M, Keating A, et al. (2015). Sca-1(+)Lin(-)CD117(-) Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Induce the Generation of Novel IRF8-Controlled Regulatory Dendritic Cells through Notch-RBP-J Signaling. Journal of Immunology, 194:4298-4308.

- [25] Zhang B, Liu R, Shi D, Liu X, Chen Y, Dou X, et al. (2009). Mesenchymal stem cells induce mature dendritic cells into a novel Jagged-2-dependent regulatory dendritic cell population. Blood, 113:46-57.

- [26] Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ (2018). Role of C-Reactive Protein at Sites of Inflammation and Infection. Frontiers in Immunology, 9.

- [27] Bisoendial RJ, Boekholdt SM, Vergeer M, Stroes ESG, Kastelein JJP (2010). C-reactive protein is a mediator of cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal, 31:2087-U1505.

16

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Table 1: Clinical classification of the COVID-19 released by the National Health and Health Commission of China

| Mild | Common | Severe | Critically severe |

| Mild clinical manifestation, None Imaging Performance | Fever, respiratory symptoms, pneumonia performance on X-ray or CT | Meet any of the followings: 1. Respiratory distress, RR ≥ 30/min; 2. Oxygen saturation ≤ 93% at rest state; 3. Arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) / Fraction of inspiration O2 (FiO2) ≤ 300mnHg, 1mmHg=0.133kPa | Meet any of the followings: 1. Respiratory failure needs mechanical ventilation; 2. Shock; 3. Combined with other organ failure, patients need ICU monitoring and treatment |

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Table 2: The general information of the enrolled patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Ctrl Patient 1 | Ctrl Patient 2 | Ctrl Patient 3 | |

| Gender | M | F | F | F | M | M | M | F | F | F |

| Age (years) | 65 | 63 | 65 | 51 | 57 | 45 | 53 | 75 | 74 | 46 |

| COVID-19 type | Critically severe | Severe | Severe | Common | Common | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe | Severe |

| Fever (°C, baseline) | 38.6 | 37.7 | 38.2 | 38.5 | 38.4 | 39.0 | 39.0 | 36.0 | 38.9 | 37.7 |

| Shortness of breath | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Oxygen saturation at rest state | 89% | 93% | 92% | 95% | 94% | 92% | 90% | 91% | 92% | 93% |

| Cough, weak, poor appetite | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| Diarrhea | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Date of diagnosed | Jan 23 | Jan 27 | Jan 25 | Feb 3 | Feb 2 | Jan 27 | Feb 3 | Feb 3 | Feb 6 | Feb 5 |

| Date of intervention (MSCs or Placebo) | Jan 31 | Feb 2 | Feb 4 | Feb 4 | Feb 4 | Feb 6 | Feb 6 | Feb 8 | Feb 6 | Feb 6 |

| Date of recovery | Feb 3 | Feb 4 | Feb 6 Discharged | Feb 6 Discharged | Feb 5 Discharged | Feb 7 | Feb 7 | Dead | ARDS | Stable |

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Table 3: Symptoms, signs and maximum body temperatures of the critically severe patient from Jan 21 to Feb 13, 2020. ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NA: Not Available

| Home | Hospital | Hospital | ICU | ICU | ICU | ICU | ICU | Out of ICU | Hospital | Hospital | |

| Date | Jan 21~22 | Jan 23 | Jan 24~29 | Jan 30 | Jan 31 | Feb 1 | Feb 2~3 | Feb 4 | Feb 5~8 | Feb 9~12 | Feb 13 |

| Fever (°C) | 37.5 | 37.8 | 37.0~38.5 | 38.6 | 38.8 | 36.8 | 36.6~36.9 | 36.8 | 36.6~36.8 | 36.5~36.9 | 36.6 |

| Shortness of breath | – | + | + | ++ | ++++ | ++ | + | – | – | – | – |

| Cough | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| Sputum | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| Oxygen saturation (without / with O2 uptake) | NA / NA | NA / NA | 97% / NA | 91% / 95% | 89% / 94% | NA / 98% | NA / 97% | NA / 96% | NA / 97% | 96% / NA | 97% / NA |

| Respiratory rate | NA | 23 | 23 | 27 | 33 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 20~22 | 20~22 | 21 |

| Treatment (Basics-1: Antipyretic, antiviral and supportive therapy. Basics-2: antiviraland supportive therapy) | NA | NA | Basics-1 | Basics-1; Mask O2 5L/min | Basics-1; Mask O2 10L/min; Cell transplant | Basics-1; Mask O25L/min | Basics-2; Mask O25L/min | Basics-2; Mask O25L/min | Basics-2; Mask O25L/min | Basics-2 | Basics-2 |

| RT-PCR of the virus | NA | Positive | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Positive (Feb 6) | NA | Negative |

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Table 4: The laboratory results of the critically severe patient. Red: the value was above the normal. Blue: the value was below the normal. NA: Not Available

| Reference range | Jan 24 | Jan 30 | Jan 31 | Feb 1 | Feb 2 | Feb 4 | Feb 6 | Feb 10 | Feb 13 | |

| C-reactive protein (ng/mL) | < 3.00 | 2.20 | 105.50 | NA | 191.00 | 83.40 | 13.60 | 22.70 | 18.30 | 10.10 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (× 109 per liter) | 1.10-3.20 | 0.94 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.93 |

| White-cell count (× 109 per liter) | 3.50-9.50 | 4.91 | 6.35 | 7.90 | 7.08 | 12.16 | 12.57 | 11.26 | 10.65 | 8.90 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (× 109 per liter) | 1.80-6.30 | 3.43 | 5.43 | 7.28 | 6.63 | 11.33 | 11.10 | 9.43 | 9.18 | 7.08 |

| Absolute monocyte count (× 109 per liter) | 0.10-0.60 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.56 |

| Red-cell count (× 1012 per liter) | 4.30-5.80 | 4.69 | 4.68 | 4.66 | 4.78 | 4.73 | 4.75 | 5.16 | 4.69 | 4.53 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 130.00-175.00 | 145.00 | 147.00 | 145.00 | 146.00 | 142.00 | 145.00 | 155.00 | 145.00 | 137.00 |

| Platelet count (× 109 per liter) | 125.00-350.00 | 153.00 | 148.00 | 169.00 | 230.00 | 271.00 | 268.00 | 279.00 | 332.00 | 279.00 |

| Absolute eosinophil count (× 109 per liter) | 0.02-0.52 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Absolute basophilic count (× 109 per liter) | 0.00-0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 5.00-21.00 | 7.00 | 23.00 | 21.70 | 19.80 | 14.20 | 15.80 | 16.50 | 12.50 | 8.70 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.00-55.00 | 41.70 | 32.30 | 29.70 | 29.90 | 31.60 | 33.00 | 32.20 | 30.10 | 29.10 |

| Aspartate amino transferase (U/L) | 15.00-40.00 | 14.00 | 33.00 | 48.00 | 57.00 | 39.00 | 34.00 | 23.00 | 25.00 | 19.00 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.00-4.00 | 2.44 | 4.24 | NA | NA | 4.73 | NA | 3.12 | 3.84 | 3.73 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | < 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | NA | NA | NA | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.15 | < 0.10 |

| Creatine kinase isoenzymes (ng/mL) | < 3.60 | 0.90 | 0.12 | NA | 5.67 | 4.24 | NA | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.61 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 50.00.310.00 | 168.00 | 231.00 | NA | 513.00 | 316.00 | NA | 47.00 | 83.00 | 40.00 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | > 90.00 | 81.30 | 68.00 | 89.60 | 99.00 | 104.00 | 92.50 | 108.10 | 97.10 | 94.10 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.50.5.30 | 3.61 | 2.74 | 3.00 | 3.42 | 3.47 | 4.18 | 4.36 | 4.69 | 4.61 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.00.147.00 | 138.50 | 132.60 | 129.50 | 132.80 | 136.90 | 135.80 | 133.80 | 134.10 | 137.70 |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 16.00.96.00 | 53.00 | 80.00 | NA | 138.00 | 77.00 | NA | 62.00 | 60.00 | 43.00 |

| Troponin (ng/mL) | < 0.056 | 0.10 | 0.07 | NA | 0.05 | 0.05 | NA | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Supplementary Materials:

Supplementary 1: The method of Mass Cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

Sample preparation for mass cytometry

PBMC samples were collected from COVID-19 infected patients treated with MSCs transplantation at baseline and on Day 6, and PBMC from a healthy donor were set as the control group. All samples were cultured with 2 μM cisplatin (195-Pt, Fluidigm) for 2 minutes before quenching with CSB (Fluidigm) to identify the viability using mass cytometry analysis. A Fix-I buffer (Fluidigm) was then used to fix cells for 15 min at room temperature, followed by washing three times with phosphate buffer solution (PBS).

Mass cytometry antibody staining and CD45 barcoding

Three samples from the healthy donor, the patient at baseline and Day 6 were stained with CD45 antibodies that were labeled with different metal tags (89, 141 and 172) to minimize internal cross reaction between samples. MaxPar × 8 Polymer Kits (Fluidigm) were used to conjugate with purified antibodies (listed in Supplemental Table 1). All metal-conjugated antibodies were titrated for optimal concentrations before use. Cells were counted and diluted into 1× 106 cells per milliliter in PBS and underwent permeabilization with 80% methanol for 15 minutes at 0°C. After triple washes in CSB, cells were cultured with antibodies in a total 50 μL CSD for 30 min in RT, triple washed in CSB and incubated with 0.125 μm intercalator in fix and perm buffer (Fluidigm) at 4 °C overnight.

Data acquisition in Helios

After cultured with intercalator, cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS and three times with deionized water. Prior to acquisition, samples were resuspended in deionized water containing 10% EQ 4 Element Beads (Fluidigm) and cell concentrations were adjusted to 1×106 cell/ml. Data acquisition was performed on a Helios mass cytometer (Fluidigm). The original FCS data were normalized and .fcs files for everyone were collected.

CyTOF Data Analysis

All .fcs files were uploaded into Cytobank, data cleaning and populations of single living cells were exported as .fcs files for further analysis. Files were loaded into R (http://www.rstudio.com), arcsinh transform was performed to signal intensities of all channels. PhenoGraph analysis was performed.

Supplementary 2: The method of the 10 x RNA-seq survey

Materials and reagents

All supplies and reagents were of the highest grade commercially available. The 0.20 μm-filters, dishes and tubes were purchased from Corning (NY, USA). CD105, CD90, CD44 and CD45 antibodies for the flow cytometry were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch gladbach, Germany). DMEM/F12, fetal bovine serum (FBS), GlutaMAXTM-I, TrypLETM Express, and penicillin and streptomycin antibiotics were purchased from Gibco (California, USA). All other reagents were analytical grade and required no further purification.

17

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Supplemental Table 1: Antibodies used in the Mass cytometry analysis.

Antigen Symbol and Mass

CD45 89Y CD45 141Pr CD19 142Nd CD5 143Nd CCR5 144Nd CD4 145Nd CD45RA 146N CD20 147Sm CD14 148Nd CD56 149Sm CD11c 150Nd CD16 151Eu TNFα 152Sm CD62L 153Eu IL-1β 154Sm CD27 155Gd CXCR3 156Gd IFN-r 158Gd CCR7 159Tb CD28 160Gd CD25 161Dy CD8 162Dy TGFβ 16Dy CD45RO 164Dy IL-12 165Ho IL-10 166Er IL-6 167Er CD206 168Er CD24 169Tm CD3 170Er CD68 171Yb CD45 172Yb HLA-DR 173Yb IL-4 174Yb CD127 176Yb CD11b 209Bi

Cell culturing

The mesenchymal stem cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2% FBS, 2%

| Antibody Clone | Source |

| HI30 | Fluidigm |

| HI30 | Fluidigm |

| HIB19 | Fluidigm |

| UCHT2 | Fluidigm |

| NP-6G4 | Fluidigm |

| RPA-T4 | Fluidigm |

| HI100 | Biolegend |

| H1 | Fluidigm |

| RMO52 | Fluidigm |

| NCAM16.2 | Fluidigm |

| Bu15 | Biolegend |

| 3G8 | Biolegend |

| MAb11 | Fluidigm |

| DREG-56 | Fluidigm |

| Polyclonal | Abcam |

| L128 | Fluidigm |

| G025H7 | Fluidigm |

| B27 | Fluidigm |

| G043H7 | Fluidigm |

| CD28.2 | Fluidigm |

| BC96 | biolegend |

| RPA-T8 | Fluidigm |

| TW46H10 | Fluidigm |

| UCHL1 | Fluidigm |

| Polyclonal | Abcam |

| JES3-9D7 | Fluidigm |

| MQ2-13A5 | Biolegend |

| 15-2 | Fluidigm |

| ML5 | Fluidigm |

| UCHT1 | Fluidigm |

| Y1/82A | Fluidigm |

| HI30 | biolegend |

| L243 | Fluidigm |

| MP4-25D2 | Biolegend |

| A019D5 | Fluidigm |

| ICRF44 | Fluidigm |

18

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

GlutaMAXTM-I, 1% antibiotics and 2 mM GlutaMAXTM-I at 37°C with 5% CO2. After three passages, MSCs were immune-phenotyped by flow cytometry for the following surface markers: CD105, CD90, CD73, CD29, HLA-DR, CD44, CD14 and CD45 (all antibodies from BD Pharmingen, San Jose, USA). And MSCs were tested for adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation to identify their characters.

Cell preparation and Library construction

Cell count and viability were examined by microscope after 0.4% trypan blue coloring. When the viability was no lower than 80%, the library construction was performed. Library was constructed using the Chromium controller (10 x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA). Briefly, single cells, reagents and Gel Beads containing barcoded oligonucleotides were encapsulated into nanoliter-sized GEMs (Gel Bead in Emulsion) using the GemCode technology. Lysis and barcoded reverse transcription of polyadenylated mRNA from single cells were performed inside every GEM. Post RT-GEMs were cleaned up and cDNA were amplified. cDNA was fragmented and fragment ends were repaired, as well as A-tailing was added to the 3’ end. The adaptors were ligated to fragments which were double sided SPRI selected. Another double sided SPRI selecting was carried out after sample index PCR. Quality control-pass libraries were sequenced. The final library was quantitated in two ways: determining the average molecule length using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer instrument; and quantifying the library by real-time quantitative PCR.

Analysis of single-cell transcriptomics data

The reads were demultiplexed by using the Cell Ranger Single Cell Software Suite (v3.1.0, 10 x Genomics) and R package Seurat (v3.1.0). The number of genes, unique molecule identifier (UMI) counts and percentage of mitochondrial genes were examined to identify outliers. Principal component analysis was used for dimensionality reduction. U-MAP was then used for two- dimensional visualization of the results. DEGs were identified with the FindConservedMarkers function in Seurat by parameters of logfc.threshold >0.25, minPct>0.25 and Padj≤0.05. KEGG pathways with FDR ≤0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched.

Supplementary 3: The detailed diagnosis and treatment procedures for the critically severe patient

On the evening of January 22, 2020, a 65-year-old man presented to the emergency department of Beijing YouAn Hospital, Beijing, with a 2-day history of cough, sputum and subjective fever. The patient wore a mask in the hospital. He disclosed to the physician that he had traveled in Wuhan, China, from December 31, 2019 to January 20, 2020 and returned to Beijing on January 20. Apart from a 10-year history of hypertension with the highest blood pressure of 180/90 mmHg ever, the patient had no other specific medical history. The physical examination showed a body temperature of 37.8, blood pressure of 138/85 mmHg, pulse of 85 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 19 breaths per minute. Lung auscultation revealed rhonchi. A blood routine examination was arranged urgently, and the result revealed that the white-cell count and absolute lymphocyte count were 4.9 × 109/L (reference range (3.5~9.5) × 109/L) and 0.94 × 109/L (reference range (1.1~3.2) × 109/L),

19

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

respectively (Table 1). According to the COVID-19 guidance released by the National Health Commission of China, the physician gave him a diagnosis of a suspected COVID-19 case and asked him to undergo medical isolation observation in the hospital. Meantime, the doctor collected his oropharyngeal swab specimen.

On January 23, 2020, the RT-PCR assay confirmed that the patient’s specimen tested positive for HCoV-19. Then the patient was admitted to an airborne-isolation unit in Beijing YouAn Hospital for clinical observation. He had no dyspnea. His consciousness was clear, and the diet and sleep were normal since he became sick. A chest computed tomography (CT) was reported as showing no evidence of infiltrates or abnormalities. The admitting diagnoses were new coronary pneumonia (common type) and hypertension III. The patient received no special care except the irbesartan, which was taken all through the treatment period.

On January 24 to January 29, the patient’s vital physical signs remained largely stable, apart from the development of intermittent fevers and shortness of breath. During this time, the patient received antipyretic therapy including 15 ml of ibuprofen suspension every 6 hours and 650 mg of acetaminophen every 6 hours. From January 26, the patient also received antiviral therapy including lopinavir and ritonavir twice a day, with the amount of 400 mg and 100 mg each time, respectively. On January 30, the patient felt severe shortness of breath and appeared fatigued. The oxygen saturation values measured by pulse oximetry decreased to as low as 91% while he was breathing ambient air. Auscultation rhonchi became worse in the middle of the double sides of the lung. An urgent chest CT clearly showed evidence of pneumonia, ground-glass opacity, in the middle lobes of the right and left lung. The other positive results of laboratory tests included the C-reactive protein rise to 105.5 g/L (reference range < 3 g/L), but the absolute lymphocyte count decreased to 0.60 × 109/L. The potassium concentration went down to 2.74 mmol/L (reference range 3.5-5.5 mmol/L). The doctors decided to change the diagnosis to COVID-19 (critically severe type), and the patient was admitted to ICU unit. More treatments were conducted consisting of mask oxygen supplementation (5 liters per minute), electrocardiograph monitoring, potassium chloride sustained release tablets (oral, 500 mg per time, 3 times per day) and more glucose and amino acid injection. Finally, the discomfort was released, and the oxygen saturation increased to 95%.

On January 31, the shortness of breath even got worse under the oxygen supplementation. The doctor speeded up the oxygen airflow to 10 liters per minute. After the patient signed an agreement to perform the MSCs transplantation, 100 ml of normal saline including 6 × 107 MSCs was intravenously injected into the patient, and no adverse events were observed in association with the infusion.

On February 1 and 2, the patient did not feel better. The third chest CT revealed that the pneumonia got worse. On February 1, the levels of C-reactive protein were 191.0 g/L, and the absolute lymphocyte count decreased badly to 0.23 × 109/L. The laboratory results showed that his liver and myocardium were very likely to be affected. The electrocardiograph monitoring showed the blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were 138/80 mmHg, 95 bpm, 33 bpm and 93% under the mask oxygen supplementation of 10 liters per minute. The doctors informed the

20

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

patient’s families of a critical condition.

However, the patient felt better on February 3, for instance, the shortness of breath was significantly recovering. On February 4, the C-reactive protein decreased to 13.6 g/L, and the absolute lymphocyte count rose to 0.58 × 109/L, which indicated that the patient was recovering rapidly. The indexes of liver and myocardium function recovered. Both fever and shortness of breath disappeared on February 5. He was rolled out of ICU. On February 9, the fourth chest CT confirmed that the pneumonia was disappearing. On February 13, the C-reactive protein concentration was 10.1 g/L, and the absolute lymphocyte count was 0.93 × 109/L. Up to now, the patient felt much better.

Supplementary 4: More results of the 10 x RNA-seq surevey

Flow cytometry analysis

The PI staining results showed that 91.60% of the total cell population was alive, and the cells were: CD105+, CD90+, CD73+, CD44+, CD29+, CD14- and CD45- (Supplemental Figure 1).

Supplemental Figure 1. Flow cytometry evaluation of transplanted MSCs (A) Single cells (87%) were gated firstly. (B) Live cells (91% of the single cells) were enrolled. (C-F) 99% of selected cells were CD105+, CD90+, CD73+, CD44+, CD29+, CD14- and CD45-.

The overview of the survey

A deep transcriptional states map of MSCs and gene expression at single-cell level was generated after the performance of 10× Genomics high throughput of RNA sequencing. The 12,500 cells were acquired in the survey, leading to 881,215,280 raw reads totally. The median number of genes and UMIs detected per cell were 4,099 and 23,971, respectively (Supplemental Figure 2). The sequencing saturation rate was 72.9%, which met the scRNA-seq requirements.

21

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Supplemental Figure 2. In the 10 x RNA-seq survey, the median number of genes and UMIs detected per cell were 4,099 (A) and 23,971 (B) as showed in the violin distribution.

MSCs marker genes expression

The scRNA-seq showed that the MSCs highly expressed ENG (CD105), THY1 (CD90), and NT5E (CD73). However, the expression of PTPRC (CD45), CD34, CD14, CD19, and HLA-DR was nearly undetected in the cells (CD45 was the only one shown in Supplemental Figure 3). The results were in accordance with the flow cytometry analysis. In Supplemental Figure 3, one point meant one cell, and red and gray color represented high expression and low expression, respectively.

Supplemental Figure 3. MSCs marker genes expression by 10 x scRNA-seq analysis. (A) CD105+, (B) CD90+, (C) CD73+, and (D) CD45-

ACE2 gene expression and DEGs between ACE2+ MSC and ACE2– MSC

Only one of the 12,500 cells was ACE2+ as shown in Supplemental Figure 4A. Furthermore, the top 60 DEGs between the ACE2+ MSC and the other nearby ACE2- MSC were shown in Supplemental Figure 4B. It is revealed that the ACE2+ MSC tended to generate pro-inflammatory function by

22

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

secreting IL-8, IL-6 and so on, while ACE2- MSC tended to generate anti-inflammatory effect by secreting BDNF and other factors.

Supplemental Figure 4. (A) ACE2 gene expression in MSCs. (B) top 60 DEGs between one ACE2+ MSC and one ACE2- MSC

23

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

TMPRSS2 gene expression and DEGs between TMPRSS2 + MSC and TMPRSS2 – MSC

Only seven of the 12,500 cells were TMPRSS2+ as shown in Supplemental Figure 5A. Furthermore, the top 60 DEGs between the TMPRSS2+ MSC and the other seven nearby TMPRSS2- MSC were shown in Supplemental Figure 5B.

Supplemental Figure 5. (A) TMPRSS2 gene expression in MSCs. (B) top 60 DEGs between seven TMPRSS2+ MSCs and seven TMPRSS2- MSCs

24

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis

KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated diseases mainly related to viral infectious diseases, cancers and endocrine and metabolic disorders (1727 genes, 1605 genes and 1384 genes, respectively). Organismal systems mainly related to endocrine and immune systems (1578 genes and 748 genes, respectively) (Supplemental Figure 6). Four enriched KEGG pathways were also involved in viral infection (Supplemental Figure 7).

Supplemental Figure 6. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis revealed that many gene expressions of MSCs were related with endocrine and immune systems.

25

chinaXiv:202002.00080v1

Supplemental Figure 7. Four enriched KEGG pathways were also involved in viral infection.

26

Posted in Most Recent

Leave a comment

Furin, a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19

Furin, a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19

Canrong WU,a,1Yueying YANG,b,1Yang LIU,bPeng ZHANG,bYaliWANG,bQiqi WANG, b Yang XU,bMingxue LI,bMengzhu ZHENG,a,* Lixia CHEN,b,* &Hua LIa,b,*

aHubei Key Laboratory of Natural Medicinal Chemistry and Resource Evaluation, School of Pharmacy, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China

bWuya College of Innovation, Key Laboratory of Structure-Based Drug Design & Discovery, Ministry of Education, Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, Shenyang 110016, China

1 These authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author: Hua Li (E-mail: li_hua@hust.edu.cn).

Lixia Chen (syzyclx@163.com).

Mengzhu Zheng (mengzhu_zheng@hust.edu.cn).

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

Abstract

A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infectious disease has broken out in Wuhan, Hubei Province since December 2019, and spread rapidly from Wuhan to other areas, which has been listed as an international concerning public health emergency. We compared the Spike proteins from four sources, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and Bat-CoVRaTG13, and found that the SARS-CoV-2 virus sequence had redundant PRRA sequences. Through a series of analyses, we propose the reason why SARS-CoV-2is more infectious than other coronaviruses. And through structure based virtual ligand screening, we foundpotentialfurin inhibitors, which might be used in the treatment of new coronary pneumonia.

Keywords:SARS-CoV-2;Spike proteins;Furin;Inhibitors;Virtual screening

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a series of acute respiratory diseases occurred in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China and then spread rapidly from Wuhan to other areas. As of February 17, 2020, a total of 71,444 patients have been diagnosed and 1,775 have died worldwide. This is caused by a novel coronavirus, which was named as “2019-nCoV” by the World Health Organization, and diseases caused by 2019-nCoV was COVID-19. 2019-nCoV, as a close relative of SARS-CoV, was classified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) on February 11, 2020.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are mainly composed of four structural proteins, including Spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E) and nucleocapsid (N) [1]. Spike, a trimeric glycoprotein of CoVs, determines diversity of CoVs and host tropism, and mediates CoVs binding to host cells surface-specific receptors and virus-cell membrane fusion [2]. Current research found that SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the beta coronavirus genus, and speculated that it may interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the surface of human cells through Spike protein, thereby infecting human respiratory epithelium cell [3]. Letko M and Munster Vthen identified the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 entry into human cells to be ACE2 [4].

Coronavirus Spike protein plays a key role in the early stages of viral infection, with the S1 domain responsible for receptor binding and the S2 domain mediating membrane fusion [5]. The process of SARS-CoV infecting the host involves two indispensable cleaving processes which affect the infectious capacity of SARS-CoV. First, Spike was cleaved into receptor-bound N-terminal S1 subunit and membrane-fusion C-terminal S2 subunit by host proteases at S1/S2 cleavage site (such as type II transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2), cathepsins B and L) [6,7]. Second, after CoVs are endocytosed by the host, the lysosomal protease mediates cleavage of S2 subunit (S2’ cleavage site) and releases the hydrophobic fusion peptide to fuse with the host cell membrane [8].

Furin, a kind of proprotein convertases (PCs), is located in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and activated by acid pH [9]. Furin can cleave precursor proteins with specific motifs to produce mature proteins with biological activity. The first (P1) and fourth (P4) amino acids at the N-terminus of the substrate cleavage site must be arginine “Arg-X-X-Arg ↓” (R-X-X-R,X: any amino acid, ↓:cleavage site). If the P2 position is basic lysine or arginine, the cleavage efficiency

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

can be improved by about 10 times [10]. Kibler KV et al. demonstrated that the Spike protein S1/S2 and S2′ cleavage sites of the infectious bronchitis virus (IBVs) Beaudette strain can be recognized by fruin, which is a distinctive feature of IBV-Beaudette with other IBVs and has stronger infection ability [11,12]. Based on the characteristics of furin’s recognition substrate sequence, some short peptide inhibitors have been developed, such as Decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone (Dec-RVKR-CMK) and modified α1-antitrypsin Portland (α1-PDX). However, the non-specific and irreversible inhibitory effects on all members of the PC family limit their application [10, 13]. No small molecule inhibitor of furin with good effect and high specificity has been found so far.

The epidemiological observations showed the infectious capacity of SARS-CoV-2 is stronger than SARS-CoV, so there are likely to be other mechanisms to make the infection of SARS-CoV-2 easier. We suppose the main possibilities as follows, first, SARS-CoV-2 RBD combining with ACE2 may have other conformations; second, the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein can also bind to other receptors besides ACE2; third, Spike is more easily cleaved by host enzymes and easily fuses with host cell membrane. We compared the Spike proteins from four sources, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and Bat-CoVRaTG13, and found that the SARS-CoV-2 virus sequence had redundant PRRA sequences. Through a series of analyses, this study propose that one of the important reasons for the high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 is a redundant furin cut site in its Spike protein.And through structure based virtual ligand screening, we proposed possible furin inhibitors, which might be potentially used in the treatment of COVID-19.

2. Methodology

2.1 Homology Spike protein blast and sequence alignment.

The Spike protein of(GB:QHR63250.1) was downloaded from NCBI nucleotide database. The protein sequence were aligned with whole database using BLASTp to search for homology viral Spike protein (Alogorithm parameters, Max target sequences: 1000, Expect threshold: 10). Multiple-sequence alignment was conducted in BLASTp online and analysis with DNAMAN and Jalview. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method in MEGA 7 software package. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test wasdetermined by 500 replicates. The Spike protein sequence analyses were

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

conducted in snapgene view.

2.2 Furin cleavage site prediction

The prediction of furin cleavage sites were carried out in ProP 1.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ProP/).

2.3 Compounds database

Approved drug database was from the subset of ZINC database, ZDD (ZINC drug database) containing 2924 compounds [14]. Natural products database was constructed by ourselves, containing 1066 chemicals separated from traditional Chinese herbals in own lab and natural-occurring potential antiviral components and derivatives. Antiviral compounds library contains 78 known antiviral drugs and reported antiviral compounds through literature search.

2.4 Homology modeling and molecular docking

Corresponding homology models predicted by Fold and Function Assignment System server for each target protein were downloaded from Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org). Alignment of two protein sequences and subsequent homology modeling were performed by bioinformatics module of ICM 3.7.3 modeling software on an Intel i7 4960 processor (MolSoft LLC, San Diego, CA). For the structure-based virtual screening, ligands were continuously resiliently made to dock with the targetthat was represented in potential energy maps by ICM 3.7.3 software, to identify possible drug candidates. 3D compounds of each database were scored according to the internal coordinate mechanics (Internal Coordinate Mechanics, ICM)[15]. Based on Monte Carlo method, stochastic global optimization procedure and pseudo-Brownian positional/torsional steps, the position of intrinsic molecular was optimized. By visually inspecting, compounds outside the active site, as well as those weakly fitting to the active site were eliminated. Compounds with Scores less than -30 or mfScores less than -100 (generally represents strong interactions) have priority to be selected. Protein-protein docking procedure was performed according to the ICM-Pro manual.

3. Results

3.1 Bioinformatics analysis reveals furin cut site in Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2

By sequence alignment of Spike protein sequence of SARS-CoV-2 with its highly homologous sequences, it was found that cleavage site Spike of SARS-CoV-2 had 4 redundant

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

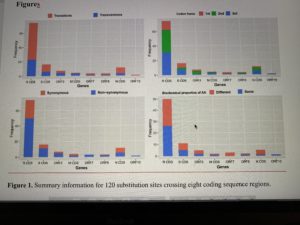

amino acids-PRRA, and these were not found in those of high homology coronavirus, which formed a furin-like restriction site as RRAR(Figure S1). Through prediction in ProP 1.0 Server, it was found the sequence was indeed easily digested by furin(Figure S2). In order to explore the evolution of this sequence, we used the BLASTp method to find 1,000 homologous Spike sequences with homology from 100% to 31%, which all from beta CoVs. Multiple sequence alignments were performed on these thousands of Spike sequences. One sequence was selected from each highly homologous class (homology greater than 98.5%) for further sequence alignment, and about 155 sequences were finally selected. A homologous multiple sequence alignment was performed on these 155 sequences, and then a phylogenetic tree was constructed(Figure 1). It is found from the phylogenetic tree that the Spike of SARS-CoV-2 exhibited the closest linkage to those of Bat-SL-CoV and SARS-CoV, and far from those of MERS-CoV, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-OC43. In general, most of the Spike protein in α-CoV does not have a furin cleavage site, most of that in gama-CoV has a furin cleavage site, and that in beta-CoV with or without furin cleavage site are common[16].

We performed furin digestion site prediction on the sequence of each type of coronavirus Spikethrough online software. It was found that all Spike with a SARS-CoV-2 Spike sequence homology greater than 40% did not have a furin cleavage site (Figure 1, Table 1), including Bat-CoV RaTG13 and SARS-CoV (with sequence identity as 97.4% and 78.6%, respectively). The furin cleavage site “RRAR” in SARS-CoV-2 is unique in its family, rendering by its unique insert of “PRRA”. The furin cleavage site of SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely to have evolved from MERS, HCoV-HKU1, and so on. From the currently available sequences in databases, it is difficult for us to find the source. Perhaps there are still many evolutionary intermediate sequences waiting to be discovered.

By analysis of the SARS -CoV-2 Spike protein sequence, it was found that most features are similar to SARS-CoV. It has an N-terminal signal peptide and is divided into two parts, S1 and S2. Among them, S1 contains N-terminal domain and receptor binding region. And S2 is mainly responsible for membrane fusion. The C-terminal region of S2 is S2′, containing a fusion peptide, Hetad repeat1, Hetad repeat 2, and a transmembrane domain(Figure 2). There are two cleavage sites between S1 and S2 ‘, named CS1 and CS2. However, there are some differences in this two cleavage sites.

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

Unlike SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 contains polybasic amino acids (RRAR) at the CS1 digestion site, and trypsin digestion efficiency will be significantly improved here[5]. More importantly, as mentioned above, this site can be recognized and cleaved by the furin enzyme. The cleavage of Spike protein promotes structural rearrangements of RBD for the adaptation to receptor, thus increasing the affinity[17]. More importantly, the digestion of Spike is an indispensable for membrane fusion of S2 part[18]. In this case, the efficiency of the SARS-CoV-2Spike protein cleavage is significantly higher than that of SARS-CoV, and the SARS-CoV-2Spike protein could be cut during the process of virus maturation (Figure 3). The receptor affinity and membrane fusion efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 would be significantly enhanced compared to that of SARS-CoV. The membrane fusion of SARS-CoV-2Spike protein is more likely to occur during endocytosis process. This may explains the current strong infectious capacity of SARS-CoV-2. So, the development of furin inhibitors may be a promising approach to block its transmissibility.

Figure1.Evolutionary relationships of taxa.The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 500 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. The evolutionary distances were

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

computed using the Poisson correction method and in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The analysis involved 155 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There are a total of 711 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. Those painted in red mean containing cleavage site in sequences and those painted in yellow mean no cleavage site in sequences.

Figure 2.Sequence analysis of Spike protein in SARS-CoV-2. It contains an N-terminal signal peptide, S1 and S2. S1 contains N-terminal domain and receptor binding region. And S2 is mainly responsible for membrane fusion. The C-terminal region of S2 is S2′, it contains a fusion peptide, HR1, HR2, and a transmembrane domain, the amino acid sequence numbers of every domain are annotated below them. Cleavage sites contained in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are marked by rhombus.

Figure 3.A schematic diagram of the process of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infecting host cells.Those protease are presented by sector in different colors. Furin can cleaveSpike in the process of viral maturation.

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

Table 1.Furin cleavage probability of Spike sequence homology

Description SARS-CoV-2 Bat-CoV-RaTG13 Bat-SL-CoV SARS-CoV Bat-CoV HKU5 MERS-CoV Rat-CoV

MHV

HCoV-HKU1 Rodent-CoV Beta-CoVsp Equine-CoV Porcine-CoV Bovine-CoV Canine-CoV Camel-CoV HKU23 Rabbit-CoV HKU14 Human-CoV OC43

Accession no.

QHR63250.1 QHR63300.1 AVP78042.1 ABF68955.1 AGP04941.1 QBM11737.1 AFG25760.1 ABS87264.1 AGT17758.1 ATP66727.1 AYR18670.1 BAS18866.1 ARC95227.1 QGW57589.1 ABG78748.1 ALA50080.1 AFE48805.1 AMK59677.1

CS1 sequence

NSPRRAR/SV QTQTNSR/SV HTASILR/ST QLTPAWR/IY PSARLAR/SD LTPRSVR/SV TAHRARR/SV TSHRARR/SI SSRRKRR/GI TARRKRR/AL ATRRAKR/DL TARRQRR/SP TSLRSRR/SL TKRRSRR/AI TQRRSRR/SI IDRRARR/FT TLQPSRR/AI KTRRSRR/AI

Furinscorea Identityb

0.620 100% 0.151 97.4% 0.170 80.3% 0.117 76.0% 0.697 37.1% 0.563 35.0% 0.879 36.3% 0.861 36.9% 0.744 36.8% 0.795 37.3% 0.753 35.9% 0.815 37.1% 0.758 36.1% 0.780 37.5% 0.832 37.1% 0.718 36.5% 0.629 37.7% 0.720 36.8%

aScores are predicted by ProP 1.0 Server. Scores above 0.5 mean furin cleavable. bIdentities compared with SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein.

3.2 Homology modeling and protein-protein docking calculation

In our previous studies (accepted by ActaPharmaceuticaSinica B), both SARS and SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD structures have been docked with human ACE2 to calculate their binding free energy. In that time, the complex structure of SARS-CoV-2 RBD with ACE2 was not available.Its energy was calculated based on the homology model generated from

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

SARS_RBD-ACE2 complex. The binding energy between the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and human ACE2 was -33.72 kJ mol-1, and that between SARS-CoV spike RBD and ACE2 was -49.22 KJ mol-1.This means the binding affinity between SARS-CoV-2 spike and ACE2 is weaker than that of SARS spike. During this manuscript was prepared, the structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD-ACE2 complex was disclosed[19]. Based on this new real structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD-ACE2 complex, we re-did the calculation and found that the binding free energy between SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and ACE2 was -50.13 KJ mol-1 (Figure S3). This means the binding affinity between SARS-CoV-2 spike and ACE2 is slightly stronger than that of SARS spike.By inspecting the crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 complex and SARS RBD-ACE2 complex, one can find that one key loop of SARS-CoV-2 RBD in the complex interface had very different conformation compared to that of SARS RBD and previous modeled SARS-CoV-2 RBD (Figure S4).

In order to further explore the possible mechanism how furin cleaves SARS-CoV-2 Spike, we perform protein-protein docking for furin and Spike. Although a Cryo-EM structure of SARS-CoV-2 Spike has been published in bioRxiv during this manuscript was prepared[20], the PDB coordinate was still not available so far. We already built a homology model of SARS-CoV-2 Spike in our previous paper submitted to another regular journal. SARS-CoV-2 Spike structure was built by using the SARS-CoVSpike structure as the temple (PDB code: 5X58)[21]. By superimposing the SARS-CoVSpike with the SARS-CoV-2 Spike, we can find that the major conformation differences between two structures are RBD domain, Arg685/677 loop region(furin/trypsin/TMPRSS2 cut site) and S2 loop region just after fusion peptide (Figure 4A).The trypsin/TMPRSS2 cut site of SARS-CoV was disordered and missing from the original Cryo-EM structure possibly due to its flexibility and without electro density. The “PRRA” inserting in SARS-CoV-2 in this region apparently generate the more flexible loop region and accessible cut site for protease. We performed protein-protein docking by setting SARS-CoV-2 Spikefurincleavage loop as the receptor, and furin active pocket as the ligand. The protein-protein docking results showed that furin acidic/negative active pocket can be well fitted onto the SARS-CoV-2 Spikebasic/positive S1/S2 protease cleavage loop with low energy (-18.43 Kcal/mol). This implies that the extra “PRRAR” loop of SARS-CoV-2 Spike renders it more fragile to the protease. And this may allow this site to be cut during the maturation, efficiently

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

enhancing the infection efficiency.

Figure 4.Protein-protein docking model of SARS-CoV-2 Spike with furin. (A) Superimposition of SARS-CoVSpike and SARS-CoV-2 Spike. Two S1/S2 protease cleavage sites and fusion peptide were shown as electrostatic surface mode. (B) Furin was docked onto the putative furin cut site (Arg685) of SARS-CoV-2 Spike. Both domains are shown as electrostatic surface mode.

3.3. Virtual ligand screening of furin protein

Structure-based virtual ligand screening method was used to screen potential furin protein inhibitors through ICM 3.7.3 modeling software (MolSoft LLC, San Diego, CA) from a ZINC Drug Database (2924 compounds), a small in-house database of natural products (including reported common antiviral components from traditional Chinese medicine) and derivatives (1066 compounds), and an antiviral compounds library contains 78 known antiviral drugs and reported antiviral compounds. Compounds with lower calculated binding energies (being expressed with scores and mfscores) are considered to have higher binding affinities with the target protein.

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

The screening results for the ZINC Drug Database (Table 2) showed that anti-tumor drugs Aminopterin, Fludarabine phosphate and Irinotecan, antibacterial drugs Sulfoxone,Lomefloxacinand Cefoperazone,antifungaldrug Hydroxystilbamidine, antivirus drugValganciclovir,hepatoprotective drugSilybin,folic acid supplementFolinic acid have higher binding affinity to furin with mfscores lower than -100 or Scores lower than -30.

Here, we show one example of screen hits, Hydroxystilbamidine, which was predicted to bind in the active site of furin with low binding energy. In the generated docking model, Hydroxystilbamidine was well fitted into the binding pocket of the substrate and adopted similar conformation as substrate analogous inhibitor MI-52 in PDB model 5JXH[22],occupied two arms’ position of MI-52 (Figure 5A). Asp159, Asp259 and Asp306 were predicted to form three hydrogen bonds with imine groups of compounds (Figure 5B). It looks like that Hydroxystilbamidine mimic at least two arginines. Weak hydrophobic interaction between His194, Leu227, the backbone of Trp254 and Asn295 with the compound may further stabilize its conformation.

Table 2. Potential furin inhibitors from ZINC drug database

No.

Drug Name

Structure

Pharmacological functions

1

Aminopterin

Anti-tumor

2

Folic acid

Vitamin B9, necessary material for the growth and reproduction of body cells

3

Sulfoxone

Antibacterial effect

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

4

Silybin

Fludarabine phosphate

Hepatoprotective effect

5

Diminazene

Insecticidal effect

6

Anti-tumor

7

L-Arginine

Nutritional supplement

8

Hydroxystilbamidine

Antifungal effect

9

Methotrexate

Antineoplastic, antirheumatic effects

10

L-dopa

Treatment of Parkinson’s disease

11

Irinotecan

Anti-tumor

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1

12

Cefoperazone

Valganciclovir

Antibacterial effect

13

Folinic acid

Folic acid supplement

14

Glycerol 3-phosphate

Intermediate for serine synthesis

15

Antivirus

16

Fosaprepitant

Treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy

17

Lomefloxacin

Antibacterial effect

18

Glutathione

Hepatoprotective effect

chinaXiv:202002.00062v1